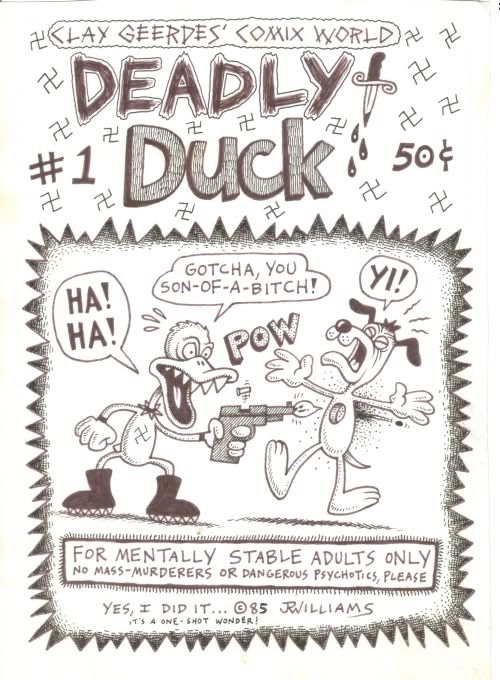

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck cover, 1985

J.R. Williams is an artist from Portland, Oregon. The pages here are from a minicomic he did in 1985 for Clay Geerdes Comix World. Clay Geerdes was an impresario of minicomics, publishing comics for many artists at the time.

What are minicomics? I guess the strictest definition would be that they were xeroxed comics printed on a piece of letter-sized paper folded over once then again to create a 4 1/4" x 5 1/2" 8-page booklet. But in general, minicomics has come to mean any self-published, micro-print-run comic (usually xeroxed). Minicomics arose with the rise of inexpensive and ubiquitous photocopiers in the 1970s. The people who drew them were amateur cartoonists inspired by the underground comics of the '60s. They formed their own networks through the mail, which in turn lead to an international movement of minicomics. (Minicomics can be seen as a subset of the zine movement of the same period. And many fans and practitioners connected to one another through the zine magazine, Factsheet Five.)

In the early 80s, minicomics were also called "newave" comics. (There is a massive collection of "Newave" comics coming out presently from Fantagraphics Books.) That's the term under which I first became aware of them, through the great comics critic Dale Luciano's mammoth survey of the "newave" scene that ran in several issues of The Comics Journal. Later, when I worked for Fantagraphics, I started writing a column about minicomics called "Minimalism" for The Comics Journal. I wrote it from 1992 to 1996, but it continues to this day, amazingly.

Many of the minicomics artists were really talented. They did minicomics for a variety of reasons, but for some of them, one reason was a lack of venues where they could get their work published commercially. The undergrounds pretty much died in the 1970s, and nothing took their place until the 80s. In the case of J.R. Williams, he found a home at Fantagraphics, where he had an ongoing series. But unlike many of his minicomics peers, he was a professional artist. When I first met him, he was working as an animator in Portland. He later moved up to Seattle to draw full time, and I later hired him to write a comic for me (Welcome to the Little Shop of Horrors).

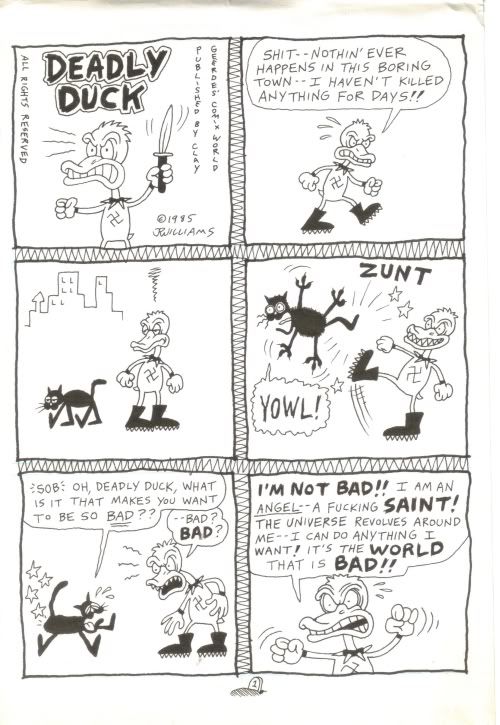

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck page 1, 1985

Deadly Duck was published in the classic minicomics format. Williams' originals are "two up"--twice the size of the printed pages. His minimal drawing style is highly appropriate to the medium in which he is working, as is his sole idea in this story. In seven tiny pages, you can't put in much plot or characterization. But it's a good size for barbaric yawps like this.

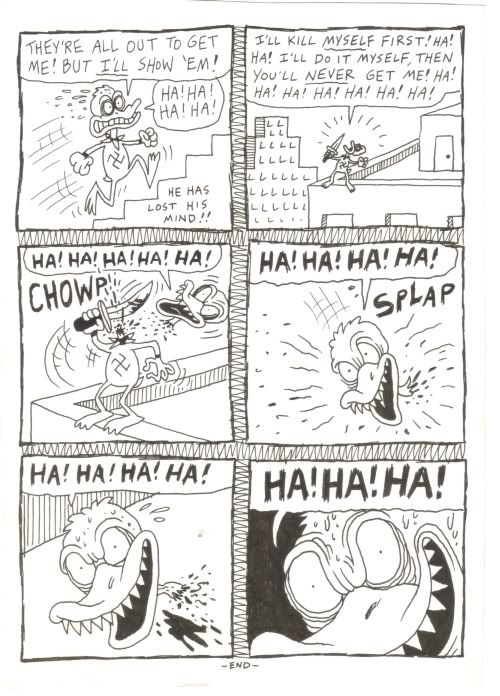

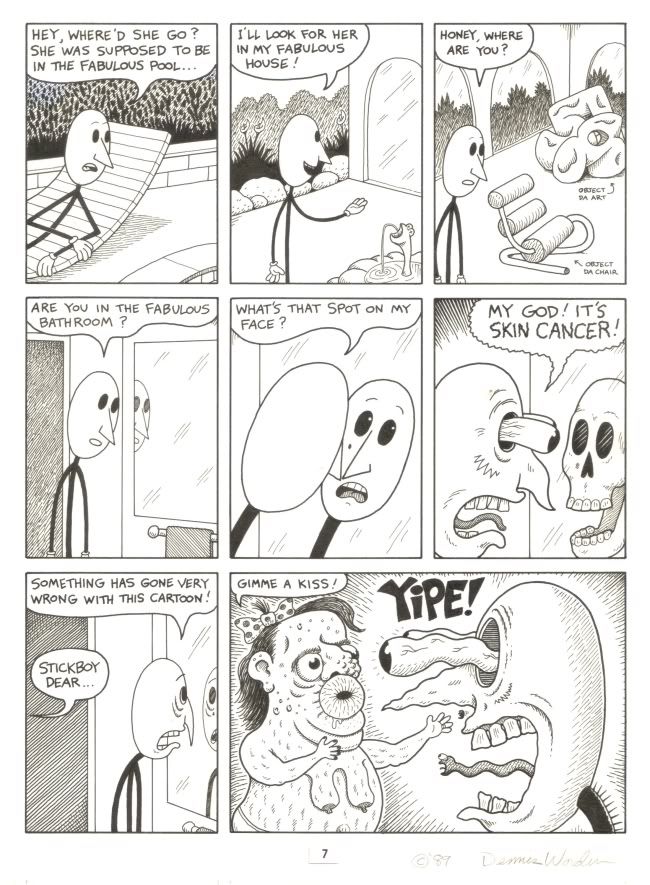

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck page 7, 1985

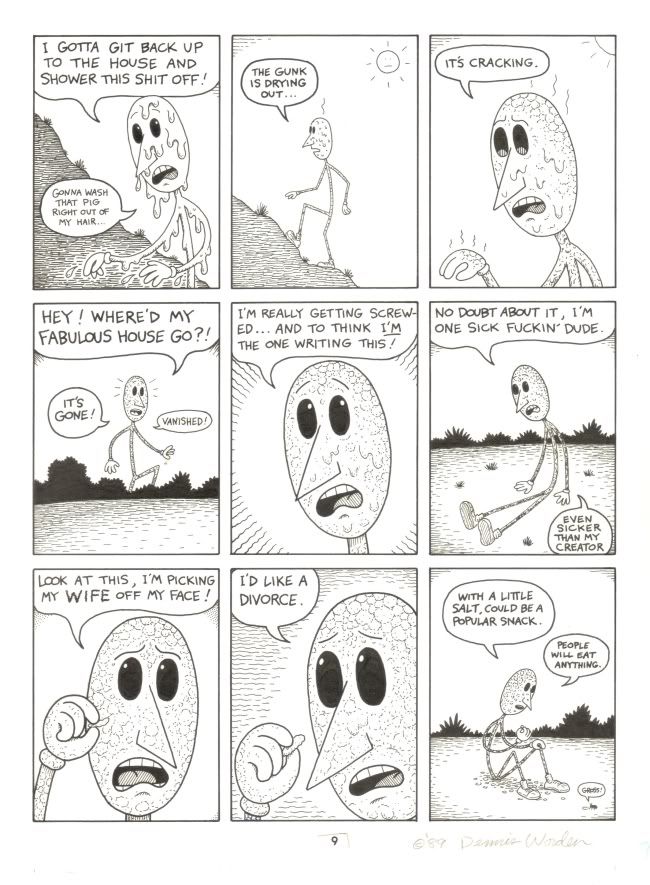

I was able to buy all eight pages directly from Williams. They are funny and drawn really well--perfect examples of what minicomics were all about in the 1980s.

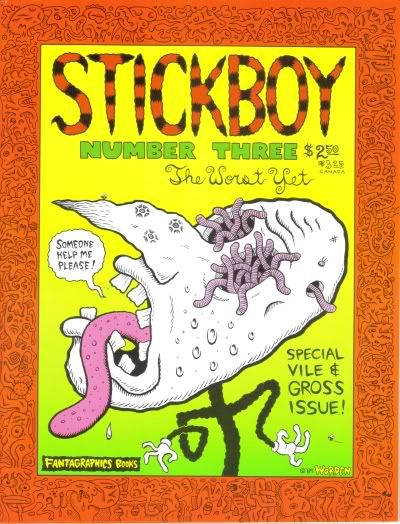

Dennis Worden comes out of the same milieu as Williams. He was from the San Diego area. He started getting published in Weirdo, had comics published by Fantagraphics and other publishers, and now does paintings, which he will happily sell to you.

I bought three pages from Stickboy #3 (Fantagraphics, 1989). Worden drew them at pretty much their final printed size (8.5" x 11"), which is not typical (most comics are drawn larger than their final printed size). But Worden's art is so precise and clean (not to mention minimal) that they reproduce very well without having to be shrunk.

Cover of Stickboy #3

Worden, like Williams, had a powerful wise-ass punk attitude (as you will see in the pages I bought), but he also was unusually philosophical. (There is a self-mocking fan letter from Wayne White in Stickboy #3 praising Worden's philosophy.) Unlike most cartoonists Worden is an intellectual--a cranky, self-taught intellectual. I think Robert Crumb provided the path. Crumb is a universal cartoonist--within his vast work, every kind of self-examination takes place. Crumb is willing to tackle philosophical and religious ideas, and his own relationship to them, in a way that I think many cartoonists avoid out of a fear of looking foolish. Not Worden--he was quite willing to do the same and defend himself against attacks on his beliefs.

I love Worden's crisp minimal art, and always thought his comics were great. As far as I know, no one ever issued a book collection of his work. So if there is a publisher out there looking for an unusual project, I would say please publish a collection of the comics of Dennis Worden.

Dennis Worden, Stickboy #3, page 7, 1989

Dennis Worden, Stickboy #3, page 9, 1989

Hey, stumbled on this and wanted to thank you for the kind words! Loved the "a cranky, self-taught intellectual". I will probably do a print-on-demand and ebook collection of my comics at some point, being as no publisher has ever expressed any interest in doing it. I did just finish writing a self-help/philosophy sort of book (no art) that's available on Amazon right now. It's called "The Way Of The Good Hedonist" (by D.D.Worden). If you liked my self-taught intellectualizing you should like it. Has many of the same themes as found in Stickboy #2 and such.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I'm glad to see that art has found a good home! Be good!

-Dennis

McDingleberry? I can't even remember creating that name! I thought it would use my real name that's on my google account. Anyway, I'm sure you figured out this is Dennis Worden.

ReplyDelete