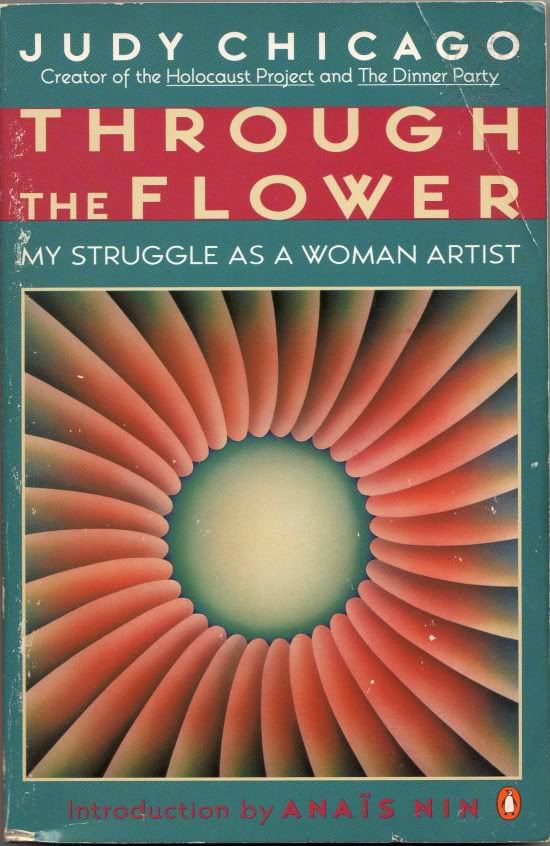

Chicago began her career as an artist in the 1960s in Los Angeles. She was one of the L.A. style minimalists, and as such, her work embraced high-tech fabrication, a high level of craftsmanship, and a certain playfulness. Think of artists like John McCracken and the Ferus boys--Ken Price, Craig Kauffman, Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston and Larry Bell. Chicago was doing pieces like this:

Judy Chicago, Car Hood, sprayed acrylic lacquer on a 1964 Corvair hood, 1963-64

You can definitely see the resemblance between what she was doing and what Billy Al Bengston was doing. And there is a high level of craft here. But she had an ambiguous relationship with craft. In Through the Flower, she sees craft as a thing that boys learned as a matter of course (in shop class) but that girls did not. I think this is really arguable, and that in a way, she is seeing craft through male eyes if she sees it that way. There were (and are) traditionally female crafts that few boys learn. Sewing and needlework, for example. I think an issue was that such crafts were not looked at as art--and that is a male failing. That they weren't looked at as craft in the context of Chicago's book is a failing on her part.

In her desire to acquire craftsmanlike skills (above and beyond what was taught to her in art school), she took a class in auto-body painting (the only woman with 250 men in the class) and another in pyrotechnics (!)--which feel totally like "boy" things to learn. Perhaps she felt she had to do these things to compete in a man's world. Certainly the piece above speaks to manly kind of things--custom car culture, in particular. (Custom car culture was a big influence on other artists in L.A. at the time, especially Robert Irwin.)

She tried to fit in with the art scene of L.A. of the early 60s. Now readers of this blog know I have often expressed admiration for the Ferus scene. Chicago--without naming names (damn!)--paints a less attractive picture.

Halfway through my last year in graduate school, I became involved with a gallery run by a man named Rolf Nelson. He used to take me to the artists' bar, Barney's Beanery, where all the artists who were considered "important" hung out. They were all men, and they spent most of their time talking about cars, motorcycles, women, and their "joints."A piece like Car Hood (which is excellent, in my opinion) was her way of trying to demonstrate to them that she could be a "tough" artist like them. She writes about her work then as hiding her real self in an attempt to fit in (to "pass"?). And maybe so, but look at this piece:

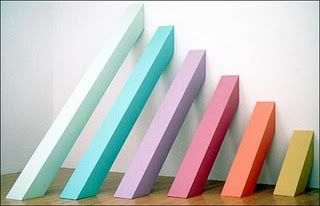

Judy Chicago, Rainbow Picket, originally sculpted in 1966 and recreated in 2004

Rainbow Picket is awesome! The colors, the angle, the way it fits against the wall. It would stand proudly next to a Sol Lewitt, a Dan Flavin, a John McCracken.

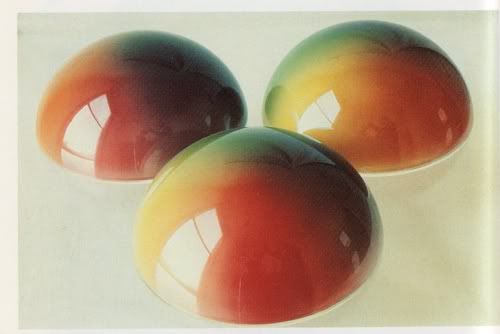

Judy Chicago, Red Dome Set, sprayed acrylic lacquer on formed acrylic, 1968

This is another really cool minimal piece. But again, Chicago felt like she was hiding from herself. In retrospect, she believes that in these round forms, her female nature is trying to come through, but she didn't want to believe it at the time. She describes how a woman artist from New York (who?) visited her studio and saw these pieces. She said, "Ah, the Venus of Willendorf." Chicago was crushed because she took it as a critical, cutting remark, and also because this woman had seen through her minimalist defenses.

So she embraced feminism. She educated herself on woman artists through history (there is a great chapter here on what she learned looking at their work, as well as studying the great women writers and thinkers). She found other women artists who had seen the sexist environment of the art world and of society in general, and who wanted to do something about it. Chicago befriended an older artist, Miriam Schapiro, and they began to work together on feminist art classes and spaces, including Womanhouse and a feminist program at CalArts.

Chicago and Schapiro eventually split their partnership over an ideological disagreement. Chicago was, essentially, a separatist. She wasn't an extreme separatist (she was married to a man, after all), but she thought there should be an entirely separate art world for women--all woman art classes, women's galleries, etc. Schapiro, rightly I think, wanted to work within the system and evolve it from within. Whatever problems she had with CalArts, she thought it was still worth fighting the battle there. And I think Schapiro was right, basically. The art world, for itrs many faults, is a less sexist place than many other parts of society. (At least, that's how it seems to me--but I'm a guy after all.)

Chicago also rejected abstraction, and started drawing and painting a lot of flowers and vaginas. Also doing a lot more performance--cartoonish plays like "Cock and Cunt," but also shamanistic performance like Woman/Atmosphere.

Judy Chicago, Woman/Atmosphere, fireworks and painted body, 1971

Despite a change in subject matter towards the real and away from the abstract, her basic painting style--mostly hard-edged with smooth, spray-painted gradations of color, remained the same. (Which reminds of Philip Guston, who around the same time also went from doing abstract paintings to figurative paintings--but his skittery bruch style and his pallet remained constant.)

Obviously her journey of self-discovery was leading somewhere. And we now know where:

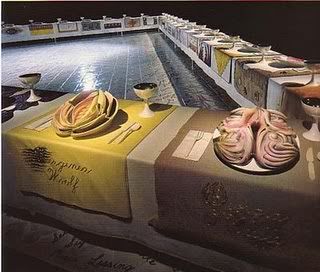

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, ceramic, porcelain, textile, 1974-79

This is her most famous work. Generally, Chicago doesn't seem to be a major figure in recent art history. It may be because people see a work like The Dinner Party and feel it is too literal, too obvious. My feeling is, so what? It's so beautiful and so cool. That outweighs the hit-you-on-the-head obviousness of it. But at the same time, I think her early minimal pieces are great, too, and really underrated. (At least, what I've seen of them.)

Feminist art is something I really want to learn more about. Fortunately, there is a movie that I think is going to be key for understanding this movement that is premiering right now at the Toronto Film Festival. It's called Women Art Revolution--A Secret History. The director, Lynn Hershman, has been working on it literally for decades. I saw a short preview of it at the Cinema Arts Festival, and it looks really good.

No comments:

Post a Comment