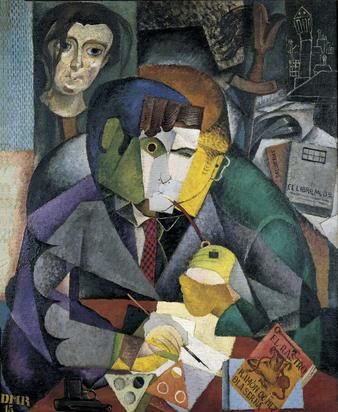

Through an ongoing artistic exchange between Museum of Fine Arts--Houston and Malba - Fundación Costantini (Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires), 39 masterworks from Malba’s permanent collection are currently on display at MFAH through August 5. Diego Rivera’s Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna invites a closer look. The oil painting reminds us that before Rivera was a muralist, he was in Paris, in close contact with Picasso and other Cubists, participating in Cubism.

Rivera’s portrait depicts his friend Ramón Gómez de la Serna, an important Spanish literary figure who departed Spain for Buenos Aires. It is a somewhat psychological portrayal showing Ramón at his writing desk on top of which lies a copy of El Rastro (The Flea Market), the book he published in 1914. Cubist fracturing and faceting are not overly harsh allowing the image to remain recognizable and close to its source. Rivera would have enjoyed that its dissection formulates a visual correlation to his friend’s writing, which has been described as fragmentary, and which today is considered a forerunner to the post-modern literary style. Octavio Paz wrote about Ramón, “for me he is the great Spanish writer, I admire his fanaticism.” Pablo Neruda expressed deep admiration.

Diego Rivera, Retrato de Ramón Gómez de la Serna (Portrait of Ramón Gómez de la Serna), 1915, oil on canvas [Malba - Fundación Costantini, Buenos Aires. © 2012 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York]

Picasso and Braque brought Cubism to its most perfect moment in 1911, four years before Rivera painted Ramón’s portrait, and three years before Rivera met Picasso. Ramón Favela and James K. Ballinger recorded that meeting in Diego Rivera: The Cubist Years “I went to Picasso’s studio,” Rivera said, “intensely keyed up to meet Our Lord, Jesus Christ.” The two of them spent the entire day and practically the whole night discussing what Cubism had already accomplished, and what its future might be. “Henceforth,” wrote Picasso biographer John Richardson, “Picasso would be Rivera’s maestro.”

If the two artists started off in friendly agreement about Cubism, by the spring of 1915 things began to disintegrate. One day they nearly “came to blows,” Richardson noted. Rivera threatened to break Picasso’s head with his “Mexican stick.”

Initially their dispute was philosophical. Rivera adhered to the overblown theories of Cubist painters Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger whose book Du Cubisme (1912) evaluated Cubism in light of newfangled ideas about relativity, simultaneity, and four-dimensionality. To burden Cubism with metaphysical notions of shifting reality and a fourth dimension, Picasso thought, was pompous and intellectually absurd. Braque also deplored the “Salon” Cubists’ self serving doctrines.

Beyond theoretical differences, Rivera imagined Picasso plagiarized some of his ideas. Rivera believed the green-on-black treatment with which he represented foliage was his personal contribution to Cubism and Picasso appropriated it, “adopted” was Richardson’s word, in more than one painting. Rivera was in a snit at the thought of being perceived a copyist, when it was Picasso who stole from him.

Snarls over foliage it turned out were only part of the story. The rest came to light with the appearance of some 1915 drawings and watercolors Picasso gave Gaby Depeyre, a Montparnasse beauty with whom he snuck off to Provence to misconduct himself while his official mistress Eva Gouel was dying. Along with the lovely nude portraits he made of Gaby, Picasso painted water colors of the rooms in which they holed up and annotated them with love notes. He also drew Self-Portrait as Suitor, which narrated sexual rivalry with Rivera.

Richardson elaborates: “In a self-portrait drawing he gave Gaby, Picasso depicts himself mockingly as a conventional, if covert suitor, cap in hand, box of chocolates in the other. He is glancing up at the studio window, where his beloved is on the lookout, waiting for Diego Rivera (in the background) to disappear so that she can signal to Picasso that the coast is clear.”

Assuredly neither professional bickering nor juicy improprieties hindered the genesis of Cubism, a profoundly transformational and entrenched moment in Western art. One bit of foolishness though tempts us to assume Rivera was too self-regarding to adequately judge his place in the movement. Offended by another artist’s insufferable theorizing about Cubism, Rivera slapped him. Despite his jackassery, from 1913 to 1917 he participated in the development of early European modernism by producing nearly 200 Cubist works before returning to Mexico to paint in the style for which he is best known.

No comments:

Post a Comment