When I posted the previous post, I wasn't entirely sure what it was. Now that I have seen Right Here, Right Now: Houston at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, featuring work by Nathaniel Donnett, Debra Barrera and Carrie Marie Schneider and spoken to Schneider about the mock interview, I have a clearer idea.

Carrie Schneider and Alex Tu, The Human Tour

The exhibit was divided into three distinct areas, one for each artist. Part of Schneider's section was sort of a greatest hits show. Leftover bits from previous works, like the Human Tour (above), Care House and Hear Our Houston, gave viewers an idea of the range of Schneider's work as well as her concerns as an artist. She is the kind of artist who places herself completely outside the realm of galleries and objects for sale. Her pieces are performances and installations, and are usually collaborative. There is a sense of social practice and of relational aesthetics at work. Much of her work involves getting under the skin of a place. The Houston metropolitan area could be said to be both her most important subject and the canvas on which she makes her artworks.

But the majority in this show was about the CAMH itself. And the interview she published the day Right Here, Right Now opened was an unofficial part of the show.

Carrie Schnieder, Balloon, 2014, custom-made ventilation equipment, hardware, and heat-sealed emergency blankets (Advisor: Gary Felix, Engineers: Lisa Augustyniak, Pietro Valsecchi)

Probably the first thing viewers notice is this giant inflated object, Balloon, which mirrors the CAMH's quadrilateral shape. The architecture of the CAMH was a starting point for much of the work Schneider assembled. She was specifically responding to a show at the CAMH from 1982 called Dreams and Schemes: Visions and Revisions for the Contemporary Arts Museum. The CAMH building was designed by Gunnar Birkerts and built in 1971. It was a bold modernist statement, all angles and sliver skin. The metal clad exterior reflected a lot of regional industrial architecture. Factories and warehouses in Houston often look like this--though usually not so sleek! The 1982 show allowed a bunch of architects, including many that were at the time building some of the hippest PoMo buildings in town (Arquitectonica and Taft Architects), to reimagine the space, whether by altering or adding to Birkerts' original design or replacing it all together. Schneider, who was given free rein to go through the CAMH's archives, exhibits a lot of documents from this exhibit, and had some of her artistic colleagues help her to create their own versions of the CAMH.

Carrie Schneider, Pool, 2014, Foam core, cardboard, blue insulation foam, paper, theatrical gel, aluminum foil, straw, cocktail umbrella, bamboo skewers, moss, worry dolls, glue, and tempera paint, 23 ¾ x 9 ¾ x 5 inches

Carrie Schneider, Bank, 2014, Gatorboard, foam core, linoleum, carpet and cork flooring samples, aluminum, wood, coffee stirrers, plastic figurines, ribbon, gold chain, paper, artist’s tape, and ballpoint pen, 27 x 10 ¾ x 5 inches

Carrie Schneider, |||||||||||, 2014, Styrofoam Whataburger cups, foam core, and hot glue, 35 x 15 ½ x 4 ½ inches

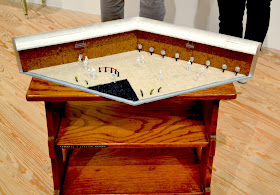

Carrie Schneider, Stephen Kraig and Gabriel Martinez, Sand Tray, 2014, Wood, paint, sand, and figurines (supplied by Texas Art Asylum), 7' x 3.5' x 9.5"

Carrie Schnieder and Gabriel Martinez, untitled, 2014, metallic in silkscreened on metallic posterboard, nails, and paint, edition of 300 (being assembled by museum-goers)

Carrie Schnieder and Gabriel Martinez, untitled, 2014, metallic in silkscreened on metallic posterboard, nails, and paint, edition of 300 (displayed on blue V-shaped wall)

This work is playful and fun. The alternate CAMHs are utopian and aimed at play. Regina Agu created her own CAMH for the show with artist-curated shows and longer hours, for example. (Correction: Regina Agu created the pedestal for that alter-CAMH, not the model itself.) This collection of alter-CAMHs becomes almost a show within the show, as if the act of curation on Schneider's part is an artistic act. This is a trend--similar shows-within-shows have appeared at the last two Whitney Biennials, for example.

Also seen at the most recent Whitney Biennial is the act of combing through an archive and displaying it as artwork--Mark Fisher/Public Collectors exhibited a mini-archive of materials related to the life of Malachi Ritscher, a devoted collector of recordings of live experimental music and dedicated political activist; and Joseph Grigely displayed selections from the papers of Gregory Battock, an art writer/curator active in the 1960s and 70s. Grigely explicitly called this work "archives as art", describing the vitrines as "an irregular modular sculpture" (Whitney Biennial 2104 catalog).

Carrie Schneider, Barthelme Board Minutes, photocopies, adhesive tape, staples, pushpins, and highlighter pen, 94 x 156 inches

Schneider does her own archive raiding for this show. There is a section of board meeting notes from the early 60s (when it was still the Contemporary Arts Association) when Donald Barthelme was the temporary chairman. She covers a large wall with blown up photocopies of the meeting notes, some of which are highlighted in yellow. These is a lot of discussion of the philosophy of the CAA as well as practical matters. Barthelme became temporary director shortly after the CAA fired Jermayne MacAgy and ended its relationship with the Menils, who were seen as overly domineering. His job was how to get the CAA back on its feet after losing such a powerful, skilled director and two very deep-pocketed board members. Many of the segments highlighted by Schneider deal with such issues of the CAA being artistically relevant as well as operationally and financially healthy.

Much of the discussion centered around Barthelme's exhibit New American Artifacts: The Ugly Show (1960). Hiding Man: A Biography of Donald Barthelme

The photocopies are hard to read. Some are fuzzy and the ones on the highest level are too far from viewers (this viewer at least) to be legible. But despite this, the gist can be understood. It's a nice piece of local art history and it makes sense that Schneider would include these documents. But the thing here is that this isn't just a trip down memory lane--Schneider is using the CAMH's past to comment on its present. While the CAMH has put on some adventurous exhibits in the past few years, nothing has been as challenging as New American Artifacts: The Ugly Show. Everything the CAMH has shown since at least 2009 has been work that fits comfortably into what the art world would accept as art. Nothing really falls outside the art world consensus space or is even liminal. For example, the homme moyen sensuel might have found the Joan Jonas/Gina Pane or Glenn Fogel exhibits incomprehensible, but not a denizen of the art world.

Carrie Schnieder, Archival materials related to key moments in CAMH's history (1960-1973); Gunnar Birkert's building design (1967-72); Sebastian "Lefty" Adler's tenure aas Director of CAMH (1966-1972), copies of newspaper and magazine articles, photocopies, and offset print catalogues

Another wall contains framed magazine and newspaper clippings. These are interviews with Sebastian "Lefty" Adler, director of the CAMH from 1966 to 1973, and they tell a story of a very different CAMH. I read these clippings again as a rebuke from the CAMH of the past to the CAMH of today. Because Adler was the director of the museum and was making statements that seem quite radical, this installation by Schneider seems specifically to be calling out current CAMH director Bill Arning.

Schneider constructed a synthetic interview by stringing together various quotes from Adler. She presented as an interview with "CAMH's director," presumably so people would initially read it as an interview with Bill Arning. Schneider told me that the reason she created this fake Glasstire post was that people are more likely to read a blog post than to read a clipping framed and placed on a wall. You can go read the interview in full, but here are a few key quotes:

Museums and art centers are so preoccupied with exhibitions that they tend to forget the artists. We do not intend to make the museum a sacred temple. We mean to research new ideas. For too long now, we in the museums have considered the artist merely as a commodity to be used, but the artist today is someone who uses [their] imagination to produce something more than just an object to be collected.

This museum cannot be either an Acropolis or a country club and it won’t be.

The education department has been a dirty word in museums, but public school teachers are vitally important. I’ve got to take time to meet with teachers and find out what their kids want and need, and not just send them a lot of stuff they don’t need. I want to get this museum involved with college students, too. Let them install shows and get them working directly with artists. It is not Culture on a Corner. We plan to bring visiting artists and to take a role in the development of the whole city, by bringing statements, via exhibitions, about urban development. One day art forms will be flowing out TO people rather than being collected IN what we now think of as museums. Art can’t be divorced from people. Art is society and society is art. Art today moves out of museums and into the whole city.

Artists today aren’t interested in selling works to collectors – at least, not the artists I want to work with. This will enable an artist to come in here and use the museum, not just show in it. We’ve got to put the human thing back into our museums, and the only people who can do it are artists.These are all things Adler said in the early 70s. (That said, it has to be remembered that what Adler showed lots of art by artists who were more than happy to sell their work to collectors.)

By creating a guerrilla fake interview with the "CAMH's director," Schneider was engaging in deconstructive criticism of the institution and its director. Museums and the art world are often the target of criticism--down in Galveston the day after Right Here, Right Now: Houston opened at the CAMH, William Powhida and Jade Townsend presented an ambitious installation, New New Berlin and Nevada Art Fair at the Galveston Artist Residency. It was critical of many aspects of the art world, including Bill Arning, to whom was assigned the role of mayor of New New Berlin. (Not a good weekend for Arning, no?)

I find Powhida's sarcastic dissections of the art world extremely amusing, and I like Mark Flood's savage take-downs as well. But these are blunt hammer blows compared to the surgical precision of Schneider's work. She expertly slipped a stiletto into the CAMH's ribcage without the CAMH even noticing, and even more astonishing is that she borrowed the stiletto from the CAMH itself. Schneider was the proverbial treacherous house guest. The only artist I can think of who has done something comparable is Hans Haacke. (I introduced Hyperallergic editor Hrag Vartanian to Carrie Schneider at the New New Berlin opening, and he congratulated her on her "Haacke hack." Damn, I wish I had said that.)

How did Arning respond? Very diplomatically. On Glasstire, he wrote "I wish I had said them but they are all from the legendary directors of CAMH’s first years in this building. The collapsing of time and the timelessness of these issues is pretty fascinating. Good piece." On a Facebook post, he commented "I would be happy if these were my quotes but if you follow the link they are from legendary earlier CAMH directors from the first years in this building. Its a cool piece in every way." What else could he say?

Schneider told me that she had written fake Glasstire post a month and a half before the show opened. She patiently sat on it until the day of the opening. She had access to Glasstire because she had been a contributor in that past. (Needless to say, Schneider's posting privileges have since been revoked.) She couldn't post to the front page of the well-known Texas online art magazine, but her post was visible if you knew the URL. She sent the URL out to several people and let the propagating qualities of social media do the rest for her.

Schneider is critical of the CAMH that is, and she has a vision of what the CAMH could be--her vision is related to Barthelme's vision and Adler's vision. The question is, will anything change? I am dubious--time institutionalizes institutions. Sclerosis sets in. The CAMH serves a purpose as it is. To me, it seems up to others to create new institutions or frameworks to operate in the ways Adler described. What the CAMH no longer does (if they ever did), Project Row Houses does. (And what PRH doesn't do, Alabama Song might.) It seems unlikely that the CAMH will ever be a radical institution again at this stage in its existence. Not impossible, but unlikely. Nonetheless, it was truly a pleasure to witness Schneider's masterful ninja attack on the very institution housing her exhibit.

Viva Alabama Song!

ReplyDeleteHi Robert, I did not create an alter-CAMH, but I contributed the pedestals for that model.

Thanks!

Regina Agu

Aargh, it's so confusing! Well, it's corrected above.

Delete