But enough about me. Collectors in general are the subject of this post. When I think about collectors, I think of people whose defining quality is their wealth. Totally unfair, but that's the image that comes to mind. After all, collectors aren't the ones with talent and vision--the artists are. So when you see collectors profiled in a magazine or newspaper, it has the exact same feel (to me) as some vapid society page profile--the latest plutocrats (or plutocrat's spouse or heir) being kissed-up to, fawned upon, because they have a lot of money and a mildly interesting hobby. I mean, if someone because rich because he or she was a brilliant businessman and then got into art collecting, that's interesting--as long as you include the first half of the story.

For example, Peter Norton is major collector of contemporary art, especially African-American art. But it is more interesting to me that he pioneered ways to retrieve lost data off of hard drives! And take the De Menils--Dominique and Jean. Dominique was the daughter of Conrad Schlumberger, co-inventer of well logging and founder of the oil services company that still bears his name. Jean eventually became pesident of the company, and the pair, fleeing the Nazi's, set up shop in Houston. I read that Jean eventually went back to guide commando raids against Schlumberger facilities in Romania--helping guys blow up his own facilities in an effort to deny the Nazis precious petroleum. This is way more interesting than the fact that the couple were major art collectors! (Even though I treasure their collection and visit the Menil Museum often.)

OK, maybe I am being harsh on collectors. There are definitely some collectors whose collecting is interesting (and even admirable) in and of itself. Like Norton Dodge, whose daredevil collecting of non-conformist and dissident Soviet Art probably rescued much of it from destruction or oblivion.

This has all been leading up to the story of Dorothy and Herbert Vogel.

The backstory to the Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection: Fifty Works for Fifty States gift is, well, sui generis to say the least. (So much so that it generated a recently released documentary, "Herb and Dorothy.") New York-born Herb, a high-school dropout and aspiring artist who worked a day job as a postal clerk, married Dorothy Hoffman of Elmira, N.Y., a Brooklyn librarian who also became an aspiring painter. The Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection is what resulted from their decision shortly thereafter, in the mid-1960s, to collect rather than make art. They earmarked Herb's modest salary for that purpose, and for much of the next four decades the pair were Zelig-like presences on the New York art scene, easily attending as many as 25 shows a week. In 1990, it would take five full-size moving vans to empty their one-bedroom Upper East Side apartment of the 2,400 works—covering every inch of wall space, stacked in crates and under beds—that they'd so voraciously collected. (Anne S. Lewis, Wall Street Journal, August 18, 2009)Now these are heroic collectors! I also like their collecting strategies and practical considerations.

They bartered with the Christos: a summer of cat-sitting for a collage preparatory work from the Valley Curtain project. The only rules, Dorothy explained, were that the work "be affordable and fit into our apartment." And be able to be carried home by bus or subway.(Of course, it helps that they had excellent taste, too.) So what are they doing with their collection? Given the value of many of the pieces, they could auction off some of the most valuable pieces, start a foundation, build a museum ("The Vogel Museum"), and bask in their own glory. Instead, they are giving it away.

In the end, 1,100 works would go to the National Gallery, and 2,500 works by 177 artists were set aside for the Fifty Works for Fifty States initiative, the brainchild of National Gallery curator Ruth Fine, who was inspired by the Kress Foundation's model for distributing its Old Masters collection. The concept was "a mini-Vogel collection for each state," explains Ms. Fine. "There were some artists—Tuttle, for example—for whom there was enough for everyone to get at least one work. Each museum got about 40 drawings and 10 paintings or objects." Gifts went first to museums with whom the Vogels had some personal connection over the years, Dorothy explained. (The Blanton [in Austin], for example, had a Vogel exhibit in 1997.) A Web site to document the project and link the recipient museums may head off the hand-wringing of those who fear that—particularly for its lesser-known artists—dispersing a collection like the Vogels' could fragment it. They have a website about this effort here. If a collector can have role-models, the Vogels are perfect!

Is there anyone like the Vogels in the world of comic art collecting? I'd say the closest (that I know of) is Glenn Bray.

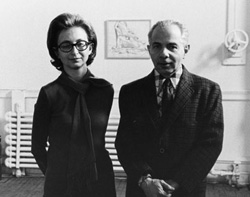

Then there are those who are more correctly identified as patrons — initiating projects, conducting obsessive research, sometimes bringing to light overlooked or forgotten niches of culture. For years, Jim Shaw kept urging me to visit Glenn Bray’s collection, but it wasn’t until I wrote a catalog essay for an exhibition of his archive of work by the visionary grotesque comic book artist Basil Wolverton that I finally made the short trek to the Valley, where Bray still manages the hardware store his father founded, and lives with his partner, Dutch underground comix legend Lena Zwalve (aka "Tante Leny"). (Doug Harvey, L.A. Weekly, May 13, 2008)If you want just a small taste of his collection, check out The Original Art of Basil Wolverton.

No comments:

Post a Comment