by

Robert Boyd

Saturday was

Artcrawl 2009--my first Artcrawl. It was drizzly and a little cold, pretty bad weather for walking from studio to studio. But that didn't keep crowds of people from showing up. I was impressed by the crowds I saw. I was a little nervous about going--would the art be any good? Just because an artist has a studio doesn't make the art worth seeing. I was a little worried it would be lots of mediocre craft-show art, bad Sunday painters, etc. And to be sure, there was a lot of art that was amatuerish, a lot that was half-baked, a lot that was derivative, a lot that was just plain inept. But who cares about that stuff? There was a lot that worked for me.

The first place I went to was the Houston Foundry. This was a place that in my most recent

Houston Streets post I mistaken identified as Blumenthal Sheet Metal. Blumenthal is across the street. But they clearly have a relationship--there are metal sculptors in the Houston Foundry, including

Michelle O'Michael. This impressive space is her studio:

Wouldn't that be a cool place to work. Right next door to it was another impressive studio for some artist who works in metal (anyone know who? I don't):

It's not all large scale metal art there (as the studio's name implies).

Christina Roos is a ceramicist, but the work of hers I liked best were her paintings and printed works.

I am often put off by deliberately child-like artwork, so I can't exactly say why these paintings charmed me so. But they did.

Manning the door at Houston Foundry was Jorge Galvan. He did a great piece that I wrote about a while back called

"This Land Was Made" at Project Row Houses. The piece that caught my attention here was "American Bred."

The punning title is a bit corny and too obvious, but the craftsmanship of the object combined with the bi-cultural irony of it cannot be denied. Also, like "This Land Was Made," it has a working-class humility that I like. It feels like an honest piece of work. And Jorge Galvan is an undergrad at U.H. Astonishing work from such a young artist, I think.

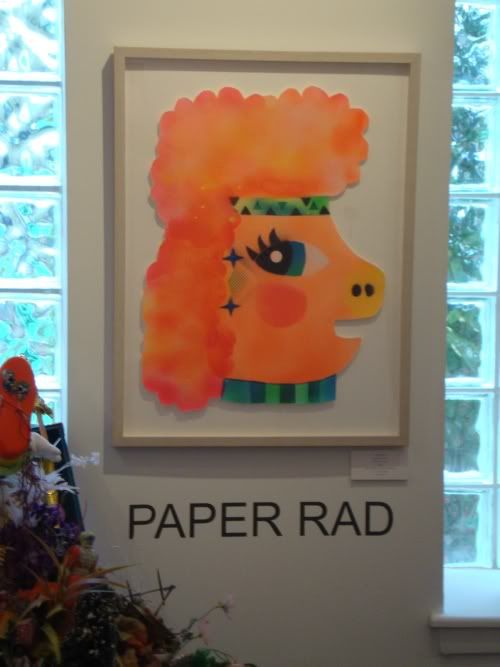

The next stop was the

Hardy and Nance Street Studios. Alex "Primo" Luster and Mike Luster are guys involved in the grafitti/street art scene in Houston. I liked Primo's studio quite a bit.

Mike Luster was showing clips from his documentary film

Stick Em Up! about the wheat-pasting poster scene in Houston (think

Give Up, for example). The art produced by people like Gonzo247, Skeez, Give Up, and Primo seems to be more-or-less completely outside of the commercial gallery world, but they have in thier own way staked claim to a part of Houston's art community (as well they should). So it was cool to see this during Artcrawl.

When I walked into

Ray Phillips' space, I was imediately knocked out by his densely layered paintings. Looking at this one, one might think about, say,

Sigmar Polke. And the one below might remind one of

Jasper Johns.

But to be honest, these paintings feel like slick versions of earlier work. Phillips is obviously a very skilled painter with a lot of visual imagination. I hate to ever suggest an artist's facilities are a handicap, but this work feels like empty mastery.

I then visited a few other studios, including the Dakota Street Lofts, but didn't see anything there that caught my eye. The next place with good art was

Mother Dog Studios. Among the many artists there was

Jo Ann Fleischhauer. The first thing that caught my eye was this collection of bird nests.

In each of those glass-walled boxes is a real bird nest. (I hope she didn't evict any birds to collect the nests). I don't want to hazard a guess about the meaning of this piece. But I like natural history museums and the conventions of display in those museums (vitrines, dioramas, etc.). (Needless to say, I love

the Museum of Jurassic Technology.) This piece seemed like a playful rearranging of conventional natural history museum concepts. (I believe this was part of an installation called

"Butterfly Effect.")

Then there were these wax houses.

These were left over from a

Project Row Houses installation called

Pocketful of Stars. I asked her if the houses were for sale, and she mentioned that a lot of people had asked the same thing, and that she thought it was weird that people would want the left-over bits of an installation. We discussed the idea of selling off bits of installations, and I couldn't think of an example of anyone who had done so (even though I would be shocked if no one did so). But I think her puzzlement over this is naive. People like souvenirs. Additionally, the houses are quite attractive by themselves as objects. Most folks are never going to have an artist's installation in their home. But having a left-over bit of one might be nice.

She had an installation up in an adjacent room.

Peony Prayer, Jo Ann Fleischhauer, 2004

If you have a spare room in your house, you can fill it with this installation for a mere $32,500. She had several of the wax-covered books in her studio space, and again I thought--these are by themselves compelling objects. The installation may be their intended home, but I think they can exist outside the installation and still be art.

Mother Dog Studios was co-founded by an artist named John Runnells, and his studio was full of amusing profane art. This piece of undressed art history amused me a lot.

Obviously this a riff on

Madame X by John Singer Sargent. And I love it, the way it is presented as a almost 19th century medical photograph (I don't know how else to describe it). But I also love that he casually left it on the floor and let a power cord hang in front of it. Not a very precious artist, is he?

One final piece from Mother Dog Studios by an artist called Naftali. I'm not sure she has a studio there (she isn't listed on the Mother Dog Studio web page). But whatever. I loved this untitled work.

I guess you would describe it as a relief. The medium is cut up bicycle inner-tubes. As Kathy Kelley explained to me later, part of the pleasure of working with inner tubes is that they are very fleshy. And indeed, this piece looks like a field of those alien-appearing primitive worms that anchor themselves to the ocean floor.

After that, I drove down to Commerce Street, where there was another little group of artist warehouses, including the now infamous

CSAW. Nothing in these spaces struck me as interesting. I did like the sculptures where Navigation goes into a tunnel under Commerce and the railroad tracks. I was held up walking from one studio to another by a passing train, so I took this photo.

Does anyone know the artist? If so, please comment!

And as I walked down Commerce Street, I saw

Skeezer Stinkfist painting in an open warehouse space (not officially part of the Artcrawl).

We had a beer and chatted a bit. If this space is where he paints, I have to say he isn't suffering for not being in CSAW. (Indeed, it seems that many of the evicted artists have gone on to bigger and better things. Living well is the best revenge.)

Then I made my way to

El Rincon Social. I'm not sure what the story is with this place--it doesn't appear to house studios. When I walked up (around 6:30 pm), the cops were there shutting down their music (a dude playing acoustic guitar--amplified, but still...). There were a bunch of paintings and objects on the walls, but it was hard to know who the artists were. Here's one that knocked me out.

This struck me as a very modern version of the old pulp painting tradition. That kind of painting was often very lush and rich. I particularly like covers of

Argosy from World War II. Obviously this painting tradition has a strong relationship with hardboiled crime fiction, and this is obviously an image from a neo-noir story. Is there a story? Is this a work of illustration, or is this a purely stand-alone work? Either way, it works. (Again, if you know the artist, please let me know if the comments. I want to give credit where credit is due.)

While I was there, I met two of the folks who run the

Station Museum, Keijiro Suzuki and Alan Schnigter (I think). This piece is by Schnigter.

The ladder really makes it, don't you think? We had a discussion about how hard it is for local institutions to collect contemporary art. They take so long to make decisions, and are paralyzed by the fear of making a wrong decision (because no one can be sure what art being made today will be worth remembering 10-20-50 years from now). So I think they depend on local collectors to buy contemporary art with the understanding that it might end up at the MFAH later (after history has time to render at least a preliminary verdict). Of course, this was just three guys idly speculating in a warehouse, so who knows?

Finally I went out to

Box 13, the last stop on my personal crawl. (I missed a few venues, which I regret. But it was hard to see everything.) They have a show up that they originally did in Nuevo Laredo. It's called Hasta La Basura Se Separa. Here's a piece by

Kathy Kelley from the show.

She told me how she liked rubber's skin-like quality, and she liked to sew her pieces. I joked that she sounded like

Buffalo Bill. But really her work reminds me of

Louise Bourgeois,

Eva Hesse and

Robert Morris. The softness and fleshiness of it, the way gravity acts on her work, are all appealing. It looks great, but it also pretty much begs you to touch it.

There were no crowds here, unfortunately. Box 13 is a little off the beaten path for this event, and there are apparently no nearby studios, so you don't get critical mass like you do off Nance or Commerce Street. Too bad, because this show has lots of great stuff.

This piece is by

Hunter Cross (his name sounds like the protagonist from a

Lee Child book.) A piece like this reminds you that Christmas is approaching. When I was a kid, the parents hid the presents in a closet that we always found. Barbed wire may have been more effective.

This piece is by

Michelle Mayer, and when you see it, you see see just a glow coming from inside the suitcase (just like

the briefcase in Pulp Fiction). As you approach it, you realize that the glow is a projected image.

But it's not a still image--someone keeps adding "things" to the suitcase.

I am not sure who the artist is here (help?), but I like it. I like the way it combines a real object with a cartoon-like depiction of puddled water.

Artist Jonathan Clark uses Box 13's most awkward exhibition space very cleverly in this installation called "The Golden Spiral."

And there are many other intriguing pieces in this show, which I highly recommend.