When you turn off the freeway just west of Fort Stockton, you feel like you are falling off the map. As long as you are on or near I-10, as I have been since I left Houston, you feel connected. I'm a big city boy, and these two-lane blacktops through the desert are a bit alien. Fort Stockton is a small town (8,283 in 2010 according to the census) but it feels like part of the great American road trip because it's full of name-brand chain hotels. I think people passing through and stopping to eat or sleep may be one of its major industries, along with agriculture.

Turning south on highway 67 is exciting because suddenly you're surrounded by mountains. At first, just purple shapes on the horizon but as you continue south they take form. Eventually, you start driving through them. These aren't huge majestic Colorado-style mountains, but after so much flatness, they are pretty impressive. Up in the mountains, you come to the town of Alpine (pop. 5,905). Just based on the drive through, Alpine seems quite nice. It has a college--Sul Ross University--and has a bit of a college town feel. But things are slow now at the tail end of summer. I filled my tank and moved on.

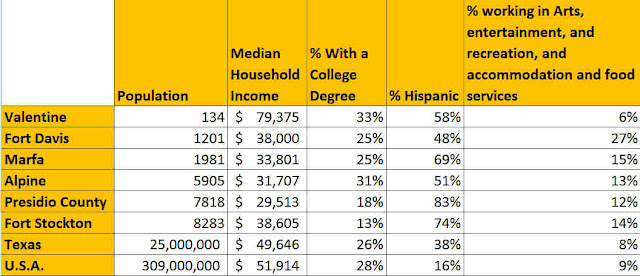

Marfa is less than 30 miles from Alpine, but you get out of the mountains before you get there (they are still all around, but distant). Fort Stockton and Alpine are bustling metropolises compared to Marfa, which has a population of 1,981. I was curious about the economy of Marfa--does all this art stuff make its people better off? This is a big question, but I figured the 2008 U.S. census might be able to shed some light.

Marfa is the county seat of Presidio County, a huge, sparsely-populated rural county in west Texas. So Marfa is doing better than the county it reigns over, but not all that much different from the towns it is near to--Fort Stockton, Fort Davis, and Alpine. (Valentine is a tiny village about 30 miles northwest of Marfa. I can't explain its numbers except to note that it is surrounded by several very large ranches, and perhaps the ranch owners and their families push the median incomes and education levels up. Because when you drive through Valentine, it looks like an impoverished hell-hole.)

Marfa's gorgeous courthouse

Marfa's gorgeous courthouseThe point is that despite all the galleries and art spaces in Marfa, most people are pretty poor compared to the rest of America and even the rest of Texas. You have two separate societies in Marfa--the mostly Hispanic and poor majority, and the well-educated, well-paid mostly Anglo art aristocracy. I went to a reading at the Marfa Book Company by Alan Heathcock, author of Volt, a short-story collection about an impoverished town where bad things happen. It was a good reading--he was amusing and the story he read was powerful. But I noticed that the crowd for it was 100% white. Indeed, when it was time for questions, many of the questioners had English accents. The Hispanic majority of Marfa stayed away.

But I felt comfortable there. Here were artistic people who loved literature, listening to an writer who had been, for a while at least, a part of their community. Here was an excellent bookstore in the most unlikely of spots. Hell, you could buy Mark Flood's book here.

Books at the Marfa Book Company

Books at the Marfa Book CompanyAnd they have their own gallery, showing interesting work by a Marfa artist named Adam Bork. According to the New York Times, Bork is an Austin transplant who in 2004

moved to Marfa to work at the Thunderbird Motel [where I am currently staying-RB], a satellite of his previous place of employment, the San Jose Hotel in Austin, Tex. Two years later he and his wife, Krista Steinhauer, a caterer and chef, bought a food truck and started Food Shark, a mobile “Mediterranean by way of West Texas” eatery. A longtime collector of vintage televisions, and a recording artist formerly known as Earthpig, Bork embraced his new home in a way he never had in the Hill Country Live Music Capital of the World. He put out a new album under his own name, moved into a geodesic dome and began creating fusion works of art unique to a multi-hyphenate of his pedigree: video installations, largely, that employ his many old TVs.Here's some of his work:

Adam Bork, The Eyes, 2012, televisions and stands

Adam Bork, The Eyes, 2012, televisions and stands

Adam Bork, Self-Portrait South Bronx (two states), 2011, light table

Adam Bork, Organ Vision, 2012

Adam Bork, Organ Vision, 2012 Adam Bork, Horizontal VI, 2012, six Commodore 1702 monitors

Adam Bork, Horizontal VI, 2012, six Commodore 1702 monitors Adam Bork, C Major/C Minor, seven televisions on stands, 2012

Adam Bork, C Major/C Minor, seven televisions on stands, 2012C Major/C Minor was my favorite because it was accompanied by long, spacey chords that appeared to be sung by the faces on the TV. I couldn't tell if the chords were made by human voices, or if they were, if they were really from the mouths opening and closing on screen. Whatever the case, the effect was hypnotic.

But I was still curious--what is the main business of Marfa? It can't be modern art because only a small portion of the population is involved in that industry. It can't even just be tourism--art and tourism work add up to 15% of the working population. A lot more than the U.S. as a whole, but about average for the area. Some people I talked to suggested the Border Patrol was a major employer, and they do have a large office here. And according to the census, it looks like about 30% are employed by the government. That includes people who work for the schools, the courthouse, and various social services, as well as the Border Patrol. And 17% work in agriculture or mining. As prominent as modern art is in Marfa, Uncle Sam pays the rent for a lot more people.

That's been the case for a long time. In the first half of the 20th century, Marfa was home to Fort D.A. Russell, a cavalry outpost, and during World War II, it also had the Marfa Army Airfield, where American soldiers trained to fly. The government has long been a major presence and employer in Marfa.

But art is really prominent. Donald Judd came here in the early 70s and started buying up the town--which I will discuss in a subsequent post. His legacy--and his name--are all over Marfa. The Judd Foundation owns several downtown buildings, and various Judd relations have offices downtown.

Judd, Judd, Judd, Judd

Judd, Judd, Judd, JuddIf Ashley and Wynonna came to town with open checkbooks, the whole city could be owned by Judds. And they'd find plenty to buy. Marfa doesn't seem to be all that healthy if judged by the number of houses with for sale signs on them.

Houses for sale in Marfa

Houses for sale in MarfaThese were just a few of the houses for sale that I saw. I asked a resident what the story was. She told me that there was a lot of churn--people come to Marfa to live and find living here is harder than it looks. Sure, they have a great bookstore, but there's no pharmacy here. But she also suggested that Marfa had been part of the same property boom that much of the rest of America had in the last decade, and that many of the "for sale" signs had been there since 2008.

And even if Marfa's art scene employs a small minority of its residents, it has made a permanent mark on the town. Marfa has more than its share of modern houses.

Marfa moderns

Marfa modernsNot to mention funky houses, like this pink one with its rough glass brick wall.

Pink, funky house

Pink, funky houseAnd of course the art is all around. After Chinati, Donald Judd's enormous personal museum, the biggest art institution in town is Ballroom Marfa. Ballroom Marfa has been here since 2003, and from what I can tell, it was a big catalyst for Marfa's current hipness. Obviously Chinati is the bedrock of Marfa's art scene, and the story has it that friends and colleagues of Donald Judd had been trickling in (and out) of the town ever since Judd first showed up in the early 70s. But Ballroom Marfa wasn't about housing a mostly unchanging collection of art the way Chinati does. Ballroom Marfa is continually doing new things--new exhibits, new performances, new film and video programs--not to mention amazing music performances. (Between Ballroom Marfa and local juke-joint Padre's, Marfa has a very happening live music scene.) This meant that post-2003, visitors to Marfa could expect to find something new every time they came.

Ballroom Marfa

Ballroom MarfaUnfortunately, Ballroom Marfa didn't have an exhibit up when I was there. (Let's just say that August is not the ideal time to visit. The action seems to really happen in September and October.) But they were running the Artists' Films International, so I stopped in and watched a few.

Elmgreen and Dragset, Prada Marfa, 2005, adobe bricks, plaster, paint, glass pane, aluminum frame, MDF, and carpet, Prada brand shoes and purses

Elmgreen and Dragset, Prada Marfa, 2005, adobe bricks, plaster, paint, glass pane, aluminum frame, MDF, and carpet, Prada brand shoes and pursesBallroom Marfa's most famous project, however, is actually about 30-odd miles out of town. This is Prada Marfa, a tiny fake Prada storefront by artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingmar Dragset. It is seriously isolated--there is nothing but a highway and a railroad track near it. Despite that, I managed to blow right past it at 90 miles an hour without noticing it. I had to backtrack to find it. It's really small--smaller than it looks in the photos.

Elmgreen and Dragset, Prada Marfa, 2005, adobe bricks, plaster, paint, glass pane, aluminum frame, MDF, and carpet, Prada brand shoes and purses

Elmgreen and Dragset, Prada Marfa, 2005, adobe bricks, plaster, paint, glass pane, aluminum frame, MDF, and carpet, Prada brand shoes and pursesThis is because it is shallow--it is far wider than it is deep. There it nothing behind the visible showroom. The doors to the nonexistent back of the building are just mirrors. In the photo above, you can see my image reflected in one of those mirrors.

Elmgreen and Dragset, Prada Marfa (and me), 2005, adobe bricks, plaster, paint, glass pane, aluminum frame, MDF, and carpet, Prada brand shoes and purses

Elmgreen and Dragset, Prada Marfa (and me), 2005, adobe bricks, plaster, paint, glass pane, aluminum frame, MDF, and carpet, Prada brand shoes and pursesOf course I took my photo in front of Prada Marfa. Everyone does. But the thing that's weird is that anyone drives a 60+ mile round trip to see it at all. It's just a joke, a humorous bit of incongruity that one one hand combines the suave urbanity of Prada with the awesome nowhereness of the desert, while at the same time making fun of the increasing trendiness of Marfa itself. While I was there, reflecting on this absurdity and my complicity with it, I was reminded of a passage from White Noise by Don DeLillo:

Several days later Murray asked me about a tourist attraction known as the most photographed barn in America. We drove 22 miles into the country around Farmington. There were meadows and apple orchards. White fences trailed through the rolling fields. Soon the sign started appearing. THE MOST PHOTOGRAPHED BARN IN AMERICA. We counted five signs before we reached the site. There were 40 cars and a tour bus in the makeshift lot. We walked along a cowpath to the slightly elevated spot set aside for viewing and photographing. All the people had cameras; some had tripods, telephoto lenses, filter kits. A man in a booth sold postcards and slides -- pictures of the barn taken from the elevated spot. We stood near a grove of trees and watched the photographers. Murray maintained a prolonged silence, occasionally scrawling some notes in a little book.Of course, before it became the most photographed conceptual art project in the desert, Prada Marfa was nothing. It has never been anything but the "accumulation of nameless energies." As I got in my car to drive back to Marfa, a truck coming from that direction slowed down and and turned in front of it. A young, hip couple got out, no doubt to take pictures of themselves in front of Prada Marfa.

"No one sees the barn," he said finally.

A long silence followed.

"Once you've seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn."

He fell silent once more. People with cameras left the elevated site, replaced by others.

"We're not here to capture an image, we're here to maintain one. Every photograph reinforces the aura. Can you feel it, Jack? An accumulation of nameless energies."

There was an extended silence. The man in the booth sold postcards and slides.

"Being here is a kind of spiritual surrender. We see only what the others see. The thousands who were here in the past, those who will come in the future. We've agreed to be part of a collective perception. It literally colors our vision. A religious experience in a way, like all tourism."

Another silence ensued.

"They are taking pictures of taking pictures," he said.

He did not speak for a while. We listened to the incessant clicking of shutter release buttons, the rustling crank of levers that advanced the film.

"What was the barn like before it was photographed?" he said. "What did it look like, how was it different from the other barns, how was it similar to other barns?"

Thunderbird Motel

Thunderbird MotelOnce Ballroom Marfa was there, new hip hotels and restaurants started opening. The Thunderbird, where I am staying, was remodeled and turned hip in 2005 (designed by Lake/Flato Architects). Food Shark opened in 2007. Cochineal opened in 2008. Hipster trailer hotel El Cosmico opened in 2009, I think. In short, your lodging and eating options in Marfa have broadened considerably in the years since Ballroom Marfa set up shop.

The Ayn Foundation is in this building

And in addition to all these places to stay and eat and hear music, art has metastisized in Marfa. There is the Ayn Foundation, which has two large painting installations in downtown Marfa. One is called September Eleven by German artist Maria Zerres, which I thought was pretty terrible. But I was surprised how much I liked their other installation, some Andy Warhol Last Supper paintings.

Andy Warhol, Last Supper paintings

Andy Warhol, Last Supper paintings  Andy Warhol, Last Supper painting

Andy Warhol, Last Supper paintingExhibitions 2D is a co-op gallery featuring a rotating collection of work by nine different American artists. The work is minimal, which fits into the Chinati vibe, but decidedly unmonumental. The gallery is modest converted house.

Exhibitions 2D gallery

John Robert Craft had some floor pieces that I liked a whole lot. His story is interesting. He didn't start making artwork seriously until he was forty. And he makes it on his family farm in Clarendon, Texas, way up in the Panhandle. It somehow makes sense that he'd bring it from one remote part of Texas to another to sell the work. But in the end, there is the work--heavy and rugged, it looks like the kind of scrap you might find in a heavy oil-field equipment manufacturer factory floor. Its weight is emphasized by its placement on the floor.

John Robert Craft, Mid-Point Bar, cast steel, 3.5" x 3.5" x 53"

John Robert Craft, Point Ring, cast iron, 21" diameter x 5"

Gloria Graham, Carbon of Carbon Dioxide, 1994, graphite, kaolin, canvas, wood panels, 34" x 170"

Gloria Graham's obsessively penciled drawing reminded me a little of Serra's, except using graphite made it seem more "drawing-like" than Serra's paint stick drawings. Graphite gives is a shininess, but it also seems somehow more obsessive than using a big fat paint stick.

Some of the galleries I wanted to see were closed. (Again, August--not ideal for Marfa). I missed Eugene Binder and Galleri Urbane (with a name like that, they should be selling Nagel prints), which had been on my list of galleries to visit. But I did make one serendipitous discovery, Arber & Sons Editions. As I was walking down a nondescript street, I heard a big hello. It was the woman who had taken our group on the guided tour of Chinati the previous day. Her name is Valerie Arber, and she was standing outside a little storefront with the following banner above it:

Arber & Sons Editions

This symbol is the "chop" for Arber & Sons Editions. (I liked that it looked like a brand such as you see on so many ranch signs around Marfa.) Robert Arber is a printmaker who apprenticed at Tamarind (one of the storied art printers in the U.S.). The Arbers came out to Marfa before everything blew up. They have long ties with Chinati--they have published prints by Judd and several other Chinati artists. And they have an annual project where they work with a former Chinati resident to produce a beautiful boxed print set, all 30 cm x 30 cm.

Daniel Göttin, SIXXS, 2003, six lithographs in the 30 x 30 cm project

Daniel Göttin, SIXXS, 2003, six lithographs in the 30 x 30 cm projectA devoted print collector could, over time, collect a bookshelf full of these handsome portfolios. The printshop itself is a small old movie theater. The lobby area acts as a showroom for Valerie Arber's own artwork and for the 30 x 30 cm project. Where the seats were is where they keep their presses (and a collection of old motorcycles), and the pair live in the projection booth.

Donald Judd prints at Arber & Son Editions, with Robert Arber in the foreground

Donald Judd prints at Arber & Son Editions, with Robert Arber in the foregroundI guess the thing about being a printmaker is that you get to keep some of the prints. So they had an amazing collection hanging on the wall (and on the floor leaning on stuff) of prints by Donald Judd, Ilya Kabakov, Bruce Nauman and more.

Bruce Nauman prints and motorcycles

Bruce Nauman prints and motorcyclesBut the coolest thing was seeing the printing gear, including litho stones, like this one with an image by David Rabinowitch.

A David Rabinowitch litho stone

That's Marfa as I experienced it except for one big thing--Chinati. And that's my next post.

When I grow up I want to live in Marfa.

ReplyDeleteFantastic report. It's unlikely I'll get to Marfa anytime soon, but this was almost as good as going. MDN

ReplyDeletehey I'm Adam Bork. Thanks for the mention. Nice article. Surprising about valentine's per capita income.

ReplyDeleteI was googling for the movie 'Far Marfa', and found your detailed article. Appreciate you digging into some of the socio-economics of the area! Fascinating!

ReplyDeleteIf you have a chance, watch the new film 'FAR MARFA'. Filmed in Marfa, with lots of local characters, including Adam Bork.

Www.farmarfa.com

Sincerly

Thanks for the mention.

ReplyDeleteBest,

Jack