by

Robert Boyd

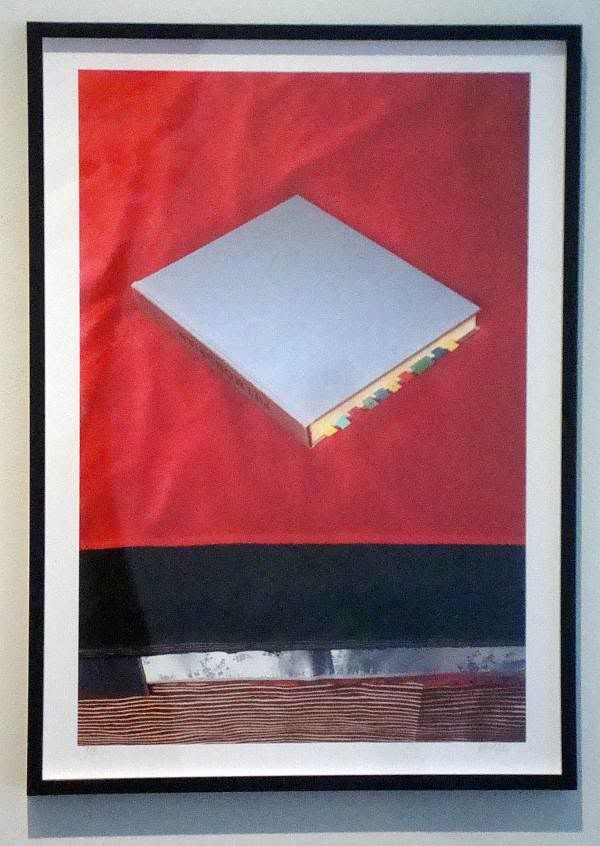

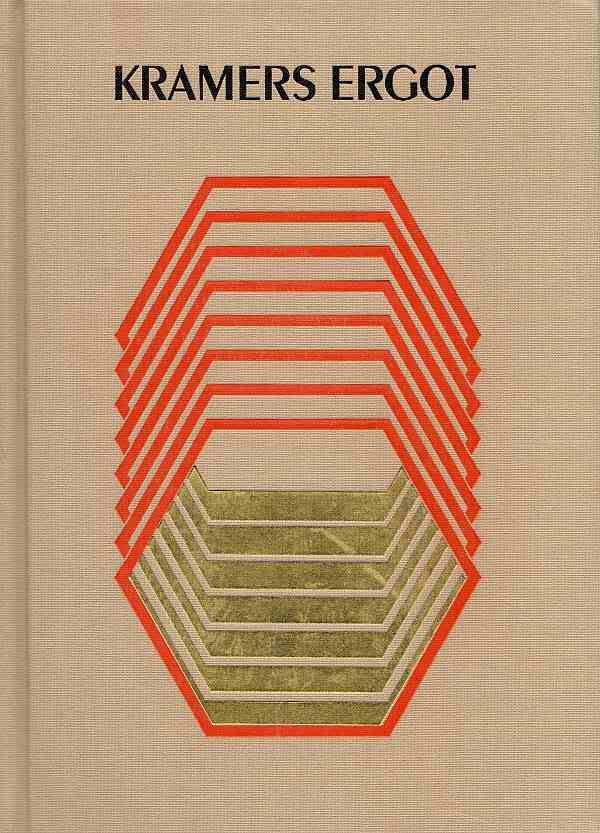

The new volume of

Kramers Ergot, edited by

Sammy Harkham, is out. This anthology started out as a small saddle-stitched 48-page magazine in 2000. Subsequent issues have been thicker and more book-like with an ever-expanding cast of contributors culled from the cream of the art comics movement.

Issue 7 was a mammoth, tabloid-sized hardcover book. The current volume is a smaller hardcover book that at first glance could be mistaken for a generic graduate level textbook published by

Wiley. The cover features the title in a fairly nondescript font, all caps. Underneath is a repeating hexagon printed in orange and gold. The image and the type are debossed into the beige cloth cover. All in all, it seems designed deliberately to be unobtrusive--the exact opposite of volume 7's attention-grabbing production.

But aside from the modesty of the exterior, one thing that struck me was how much

Kramers Ergot 8 follows the classic structure of art comics anthologies going back to

RAW (1980 to 1991) edited by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly and

Weirdo (1981 to 1993) edited by Robert Crumb, Peter Bagge, and Aline Kominsky. Like its antecedents,

Kramers Ergot features avant garde comics that shade over into the art world. (With

Weirdo, you had artists like Raymond Pettibon and Robert Crumb;

RAW featured work by David Sandlin and Gary Panter.) Like

Weirdo and

RAW,

Kramer's Ergot is a collection of short pieces. And like it's predecessors,

Kramer's Ergot reprints of older work that no one would hitherto group with art comics. (With

Weirdo, there was an incredible naive strip featuring frogs;

RAW famously rediscovered the work of Fletcher Hanks.) Why would a comics anthology operating in 2012 in a quite different context as these earlier anthologies resemble them so much?

When I say different context, let me emphasize that when

RAW and

Weirdo were in their heyday, there were very few "graphic novels"--certain none that had a readership outside the comics subculture. Comics scarcely existed in the world of educated, artistically-sophisticated readers and viewers. The work that was interesting to Crumb, Spiegelman and Mouly at the beginning

Weirdo and

RAW was work that had

no audience. I get the impression that Spiegelman and Mouly had a good idea of their desired constituency. They wanted to reach the artistically sophisticated readers in New York City--their peers, in other words.

Weirdo was effectively aiming for readers interested in seeing work extremely far out of the mainstream--comics by the insane, the homeless, the totally untrained. Weirdo in the beginning was an

art brut comic.

Given that for the most part,

Weirdo and

RAW were presenting works that had no pre-existing audience, it made sense to make these magazines anthologies. None of the editors knew which artists would resonate, and given their limited resources, it would have been unfair to gamble everything on one artist. An anthology was a safer bet.

But why did they publish the earlier work? I think in part because the work they were doing was such a departure from comics that had come before that they felt a need to establish an alternate art history of comics. This is not a history in the sense that the editors and cartoonists were influenced by these earlier artists (who were often extremely obscure). Instead, they wanted to show how aspects of their current practice had been anticipated. For example, Fletcher Hanks, a very primitive superhero/adventure/science fiction artist active only from 1939 to 1941, was rediscovered and reprinted in

RAW.

RAW was also one of the first venues to publish the work of Henry Darger.

So flash forward to 2012. The context for art comics has changed substantially. The graphic novel is a fairly popular and well-established form, thanks in part to Art Speigelman's

Maus. Cartoonists whose thematic and formal approaches to comics are highly sophisticated have had success with their own books (for example, Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware). And yet,

Kramer's Ergot 8, published 30 years after the first issues of

RAW and

Weirdo (and 20 years after those anthologies wound down), resembles them in structure. I think I know the reason why. The way to view this is to think about how cutting edge art enters the art world. If you want to show artwork that is on the very edge of contemporary art practice, you will likely show it in an artist-sun or alternative space. It will likely show up in a group show first. Solos shows, commercial galleries, and museums come later. The reason for this are the same as the reasons for the format of

Kramers Ergot 8--this is still the safest and best way to introduce new, challenging work to viewers. A museum won't show this work until it has been validated by criticism and exhibition history. A commercial gallery won't show it until some commercial possibilities have been evinced. A solo show is probably out of the question because you (the gallery director) will worry about what the board of directors might think if the show is a flop. The classic art comics anthology, like the cutting edge group show at an alternative gallery, is a strategy of hedging.

Gary Panter, Jimbo page 9, 2010

Gary Panter, Jimbo page 9, 2010

Hedging may be the reason Harkham opens with a story by

Gary Panter. Panter is one of those liminal artists, existing in the outskirts of the comics world and the art world. As one of the

RAW artists, his work has a

pedigree. The story here, featuring his now somewhat archaic punk character Jimbo, is typical and excellent. In Jimbo's world, fast food joints are dangerous robotic entities. Jimbo lives in a consumerist dystopia, in this case a

Brave New World-like space of entertainment as narcotic. It's not the most original idea, but Panter does it well. This story is curiously linear, with clear (if slightly ratty) drawing--very unlike some of his earlier classic work, such as

Dal-Tokyo. When I first encountered Panter's comics in the early 80s, I was challenged by them. They worked against comics conventions I knew. I loved them because they seemed so punk. But in 20-odd years, Panter's ruptures have become familiar, and he seems less interested in playing with the form of comics. His work, curiously, is some of the most conservative in

Kramer's Ergot.

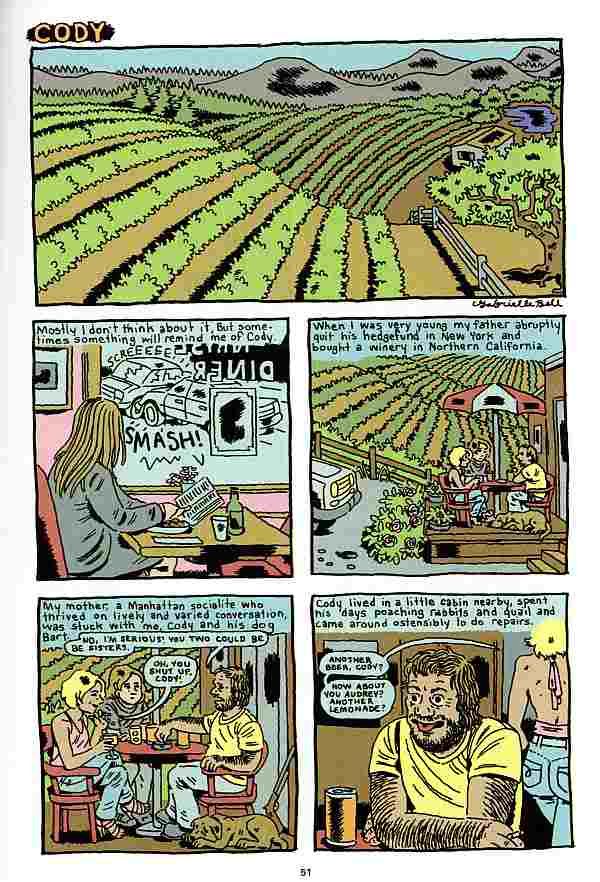

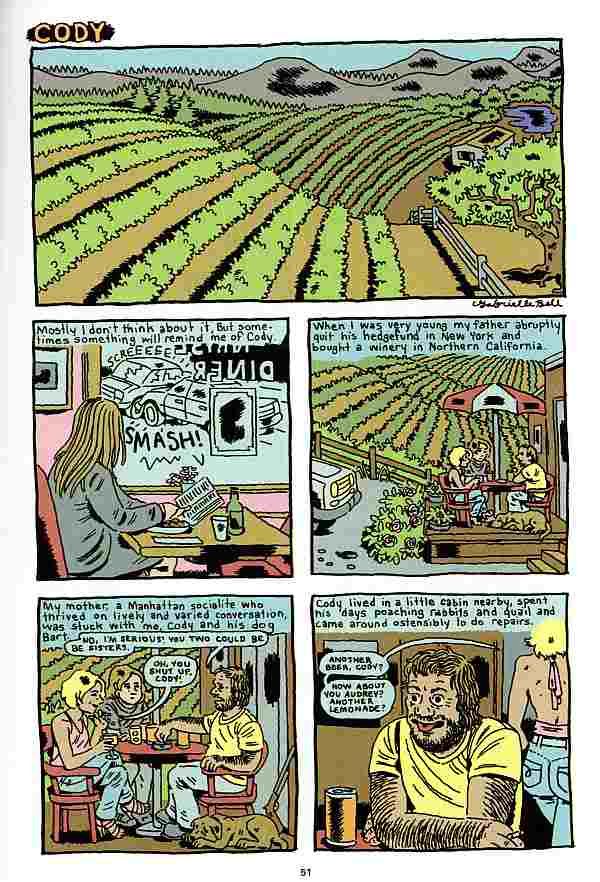

Gabrielle Bell, "Cody" page 1, 2012

Gabrielle Bell, "Cody" page 1, 2012

The same could be said about

Gabrielle Bell's story "Cody." The artwork is fairly polished and realistic (although I will say that if I saw this 30 years ago, I would have seen it as radical or experimental--which shows how much the baseline has changed). The story pretends to be autobiographical, and the set-up will strike readers as not only very realistic, but also as fitting into the tradition of alternative comics. In 1995,

illustrator Debbie Dreschler started publishing

a series of stories of childhood incest that had a powerful affect on the readers and creators of art comics. "Cody" at first seems similar to those Dreschler stories. But it takes a turn into unreality when the Bell character (age 13 in the story) tells her father about Cody's unwanted sexual advances. It turns out that her father was being blackmailed by Cody, and decided that since Cody was blackmailing him

and about to start molesting his daughter, he had to go. Bell's father kills Cody and the two of them dispose of the body. Is any portion of this story true? Was there a creepy guy named Cody who said uncomfortable sexual things to her? (I assume she didn't just out her father as a murderer.) This kind of question comes up a lot when you read Gabrielle Bell's work. It operates in the autobiographical space--a venerable space in art comics that was dominant in the late 80s and 90s. But Bell keeps undermining autobiography. ("Cody" is the only "autobiographical" story in

Kramer's Ergot 8.)

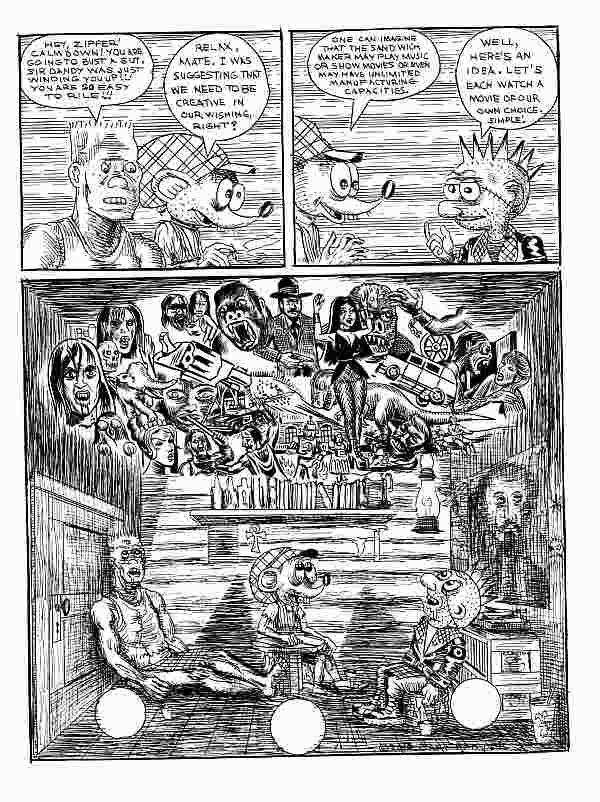

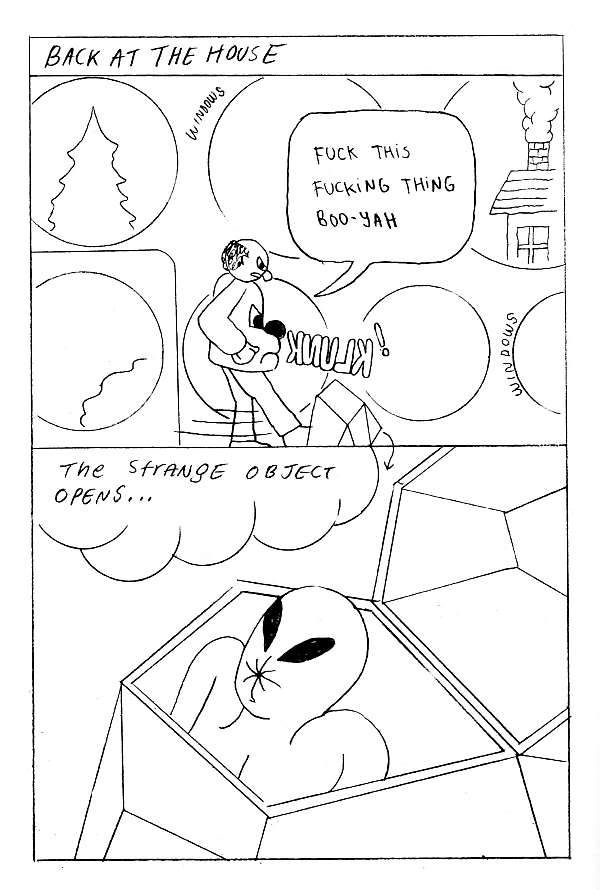

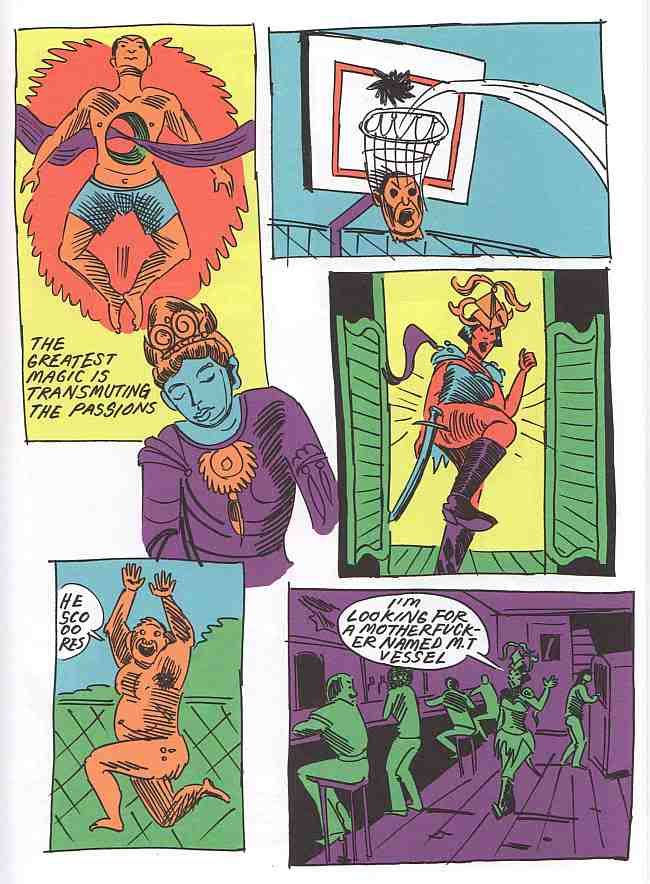

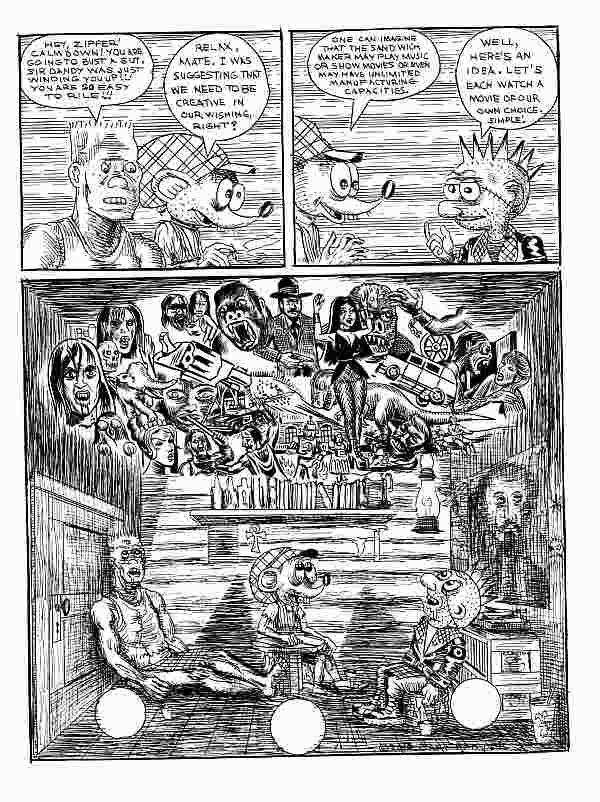

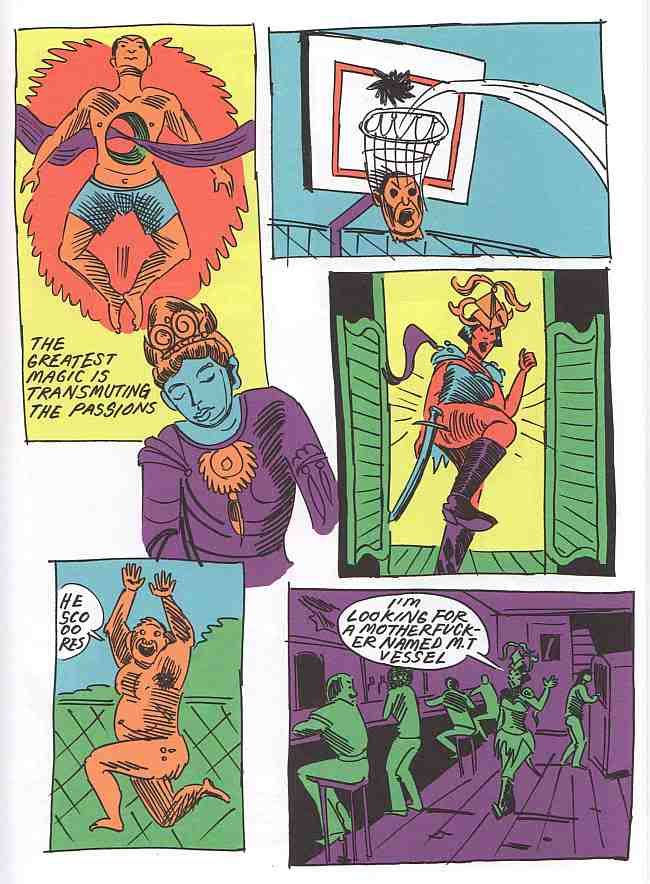

Ben Jones, "The Ultimate Character" page 10, 2012

Ben Jones is more typical of the type of artist that I associate with the

Kramer's Ergot esthetic. His story "The Ultimate Character 2002" leaves behind most of the artistic concerns of the 80s and 90s alternative comics movement. His drawing is extremely unslick, but at the same time avoids the aggressive quality of early Gary Panter, Lynda Barry or Julie Doucet. The title reveals a concern about "characters," but the modern cartoonist's concern with characters is quite different from the traditional notion of characters as fictional persons with personalities and complexities (a more literary idea of a character). In Jones' comic, the word "character" means a personage with highly visual features that make him memorable and trademarkable. In this comic, the "ultimate characters" are two people with giant dog-heads for bodies. Extremely memorable and visual (once you've seen them, you will be able to recognize them by their profiles), they are characters in the new sense of the word. The unnamed pair find a strange object, they try and fail to sell it on Antiques Roadshow, and find that the object contained the body of an alien, which one of the giant dog heads eats. The drawing is minimal and lazy--it contains barely enough information to tell the story. In a way, I was reminded of a certain strain of artwork I've been seeing lately, where artists seem to be creating minimalist objects, but using deliberately shabby materials (for example,

Cordy Ryman). This work is in dialogue with Minimalism and Post-Minimalism. I see artists like Ben Jones as in dialogue with earlier art comics pioneers like Gary Panter. (Jones is, like Panter, an artist in the art world, both as a solo artist and formerly as a member of the collective

Paper Rad.)

I have a theory about these hybrid artists who live in the comics world and the art world simultaneously. I think they don't care about comics. Comics are another means of expression, no more important than any other. Therefore, they have no interest in elevating the form--a major project of the

RAW/Weirdo generation. Using an extremely low-brow genres is just fine with them because to them it is just an aspect of the medium they are playing with. Highly polished drawing (like, say, the drawing of Dan Clowes or Chris Ware) is also not particularly important. What's important is to provide enough signifiers that tell a viewer that this is a

comic you are reading. If this is their goal, it makes sense that their subject matter would not be autobiographical, or similar to realistic novels, or designed in such a clever way that you might not recognize it as a comic at first. Or, in other words, their approach is unlike the majority of American and European art comics of the 80s and 90s and most of the 2000s.

I think of these cartoonists as the "Art School Generation." It's not just that they went to art school; lots of cartoonists do that. It's that they went to

elite art schools, and that some went even further and got MFAs there. They are steeped in the current thinking in contemporary art. They didn't rebel against their instruction that way Chris Ware did (Ware went to the

School of the Art Institute of Chicago, one of the most elite art schools in the U.S.).

Anya Davidson, "Barbarian Bitch" page 5, 2012

Anya Davidson, "Barbarian Bitch" page 5, 2012

Anya Davidson is, as far as I can tell, a member of the Art School Generation. She offers a comic called "Barbarian Bitch" which also embodies some of the approaches of the current generation--minimal, adolescent drawing, extreme cartoonish violence, and use of highly discredited genres (sword and sorcery/barbarian adventures in this case). In "Barbarian Bitch," Davidson

weaves Buddhist sayings through the story (

these sayings are by Atisha, an 11th century Tibetan Buddhist master). This is actually a bit unusual--you see plenty of references to pop culture in these comics, but not so much to classical culture. I don't know much about Davidson, but what I can glean from the internet is that she may be a graduate of

SAIC.

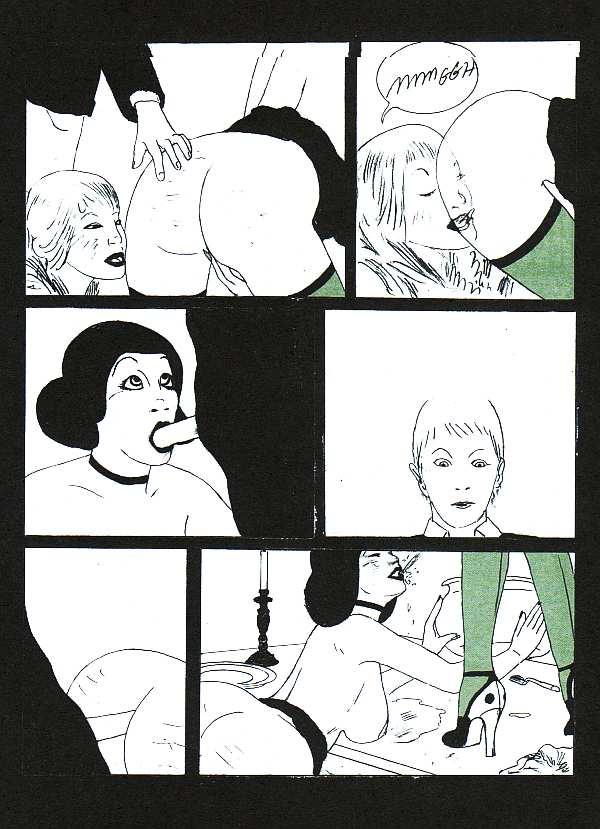

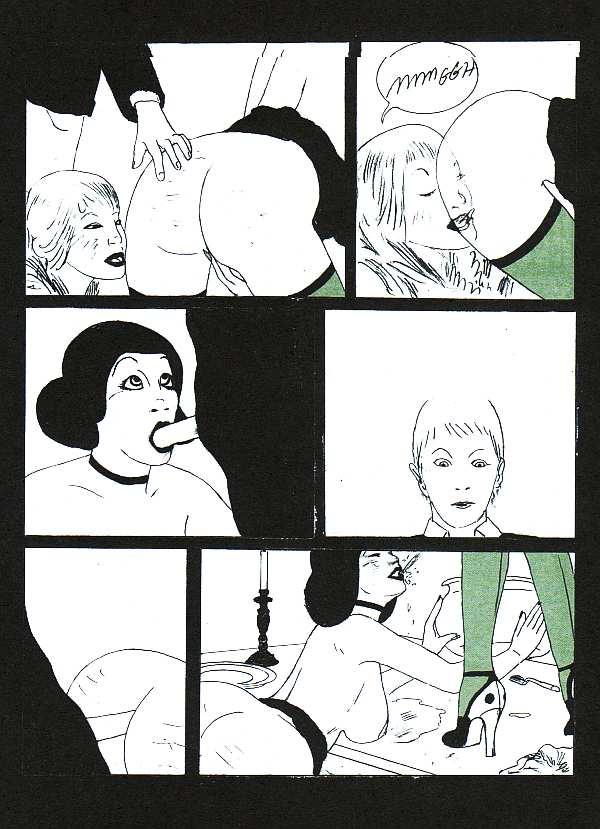

CF (Christopher Forgues), "Warm Genetics House" page 8, 2011

CF (Christopher Forgues), "Warm Genetics House" page 8, 2011

Perhaps the most influential of this generation of artists is

CF (Christopher Forgues). His story in this issue of

Kramer's Ergot is "Warm Genetics House," a perverse story of a male teacher who invites a female student to dinner at his house, where he and his sister have violent sex with the student. Forgues comes out of an elite art school background as well--

The Massachusetts College of Art and Design. (Ben Jones is also an alumnus of MassArts.) I've seen work by Forgues that is highly polished with anatomically correct figures. But for his purposes, that kind of drawing isn't necessary. Here the lowbrow genre he references is porn, and he draws it just well enough to be comprehensible (even if the enigmatic story as a whole is not).

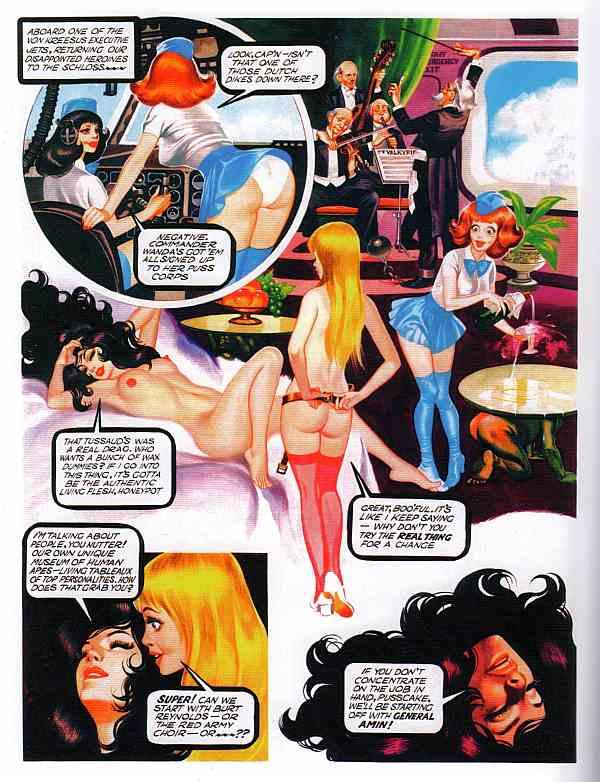

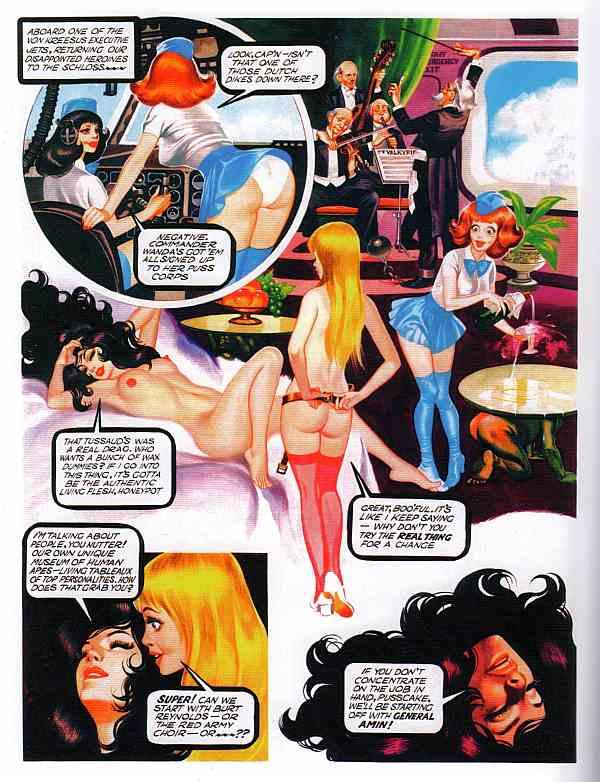

Ron Embleton and Frederic Mullally, Oh, Wicked Wanda page 6, 1975

Ron Embleton and Frederic Mullally, Oh, Wicked Wanda page 6, 1975

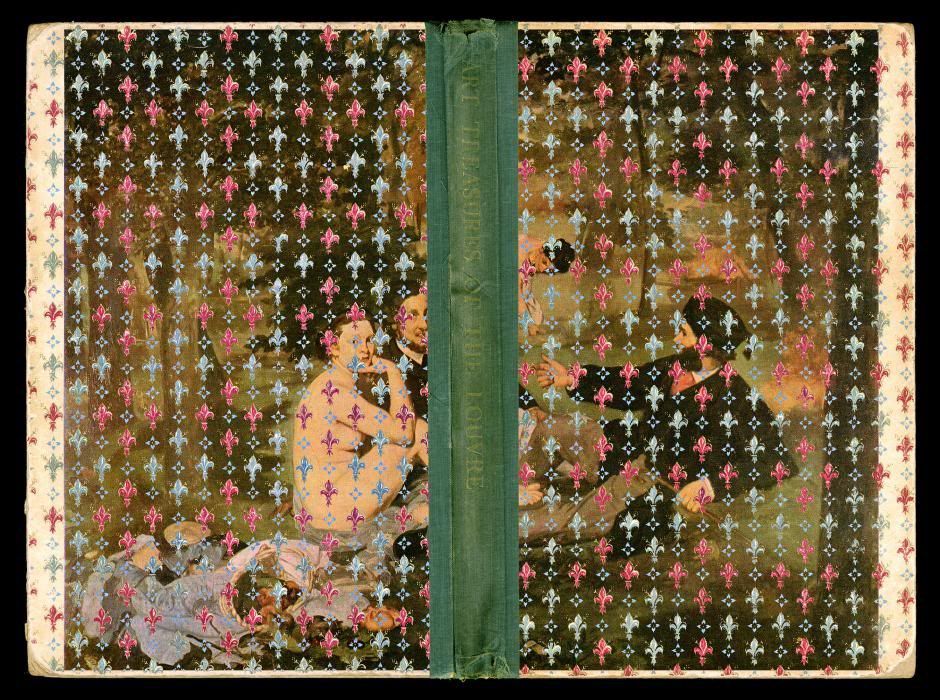

And perhaps that reference to porn is why Harkham included a lengthy section of

Oh, Wicked Wanda! by

Ron Embleton and Frederic Mullalley. This comic was published in the 70s in

Penthouse. Like most "sexy" comics published in men's magazines in the 60s and 70s, it was very highly produced while being completely inane at the same time. Harkham devotes an astonishing 40 pages to this tripe. Why? I'm not sure but he may be thinking that this is an exemplar of dopey porno comics, which is the kind of thing that can be quoted by art-school generation cartoonists like CF. (In CF's case, "Warm Genetics House" seems less like

Oh, Wicked Wanda than like

The Adventures of Phoebe Zeit-Geist by Michale O'Donoghue and Frank Springer, minus the humor.)

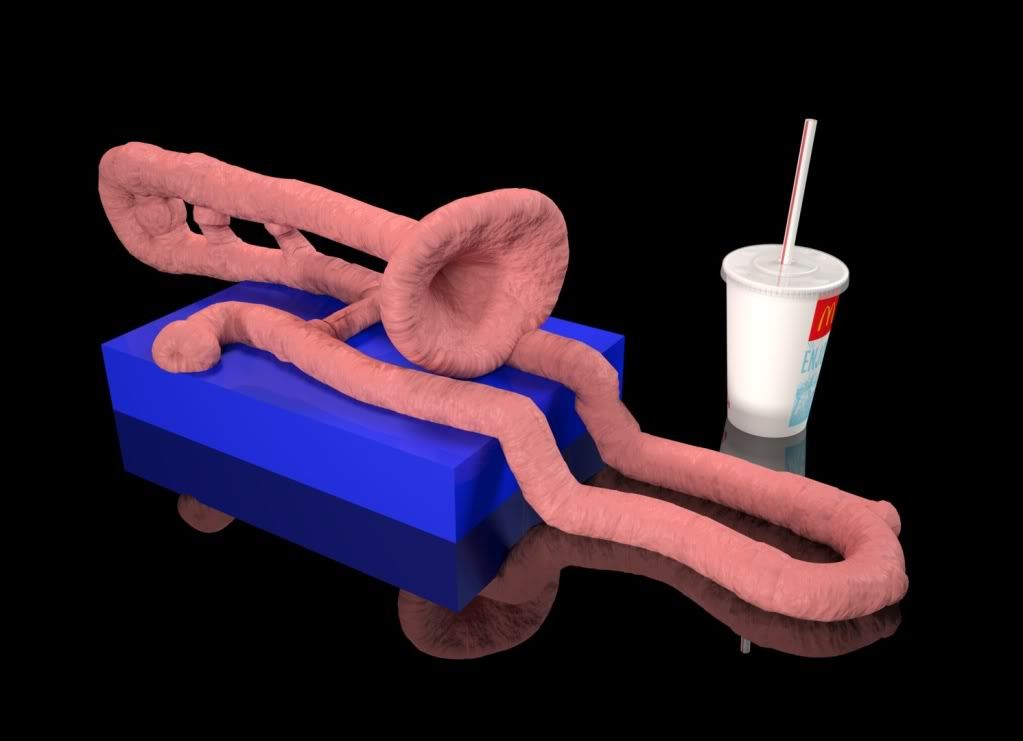

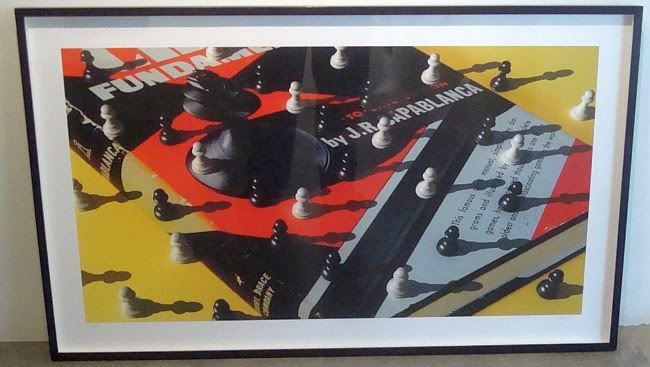

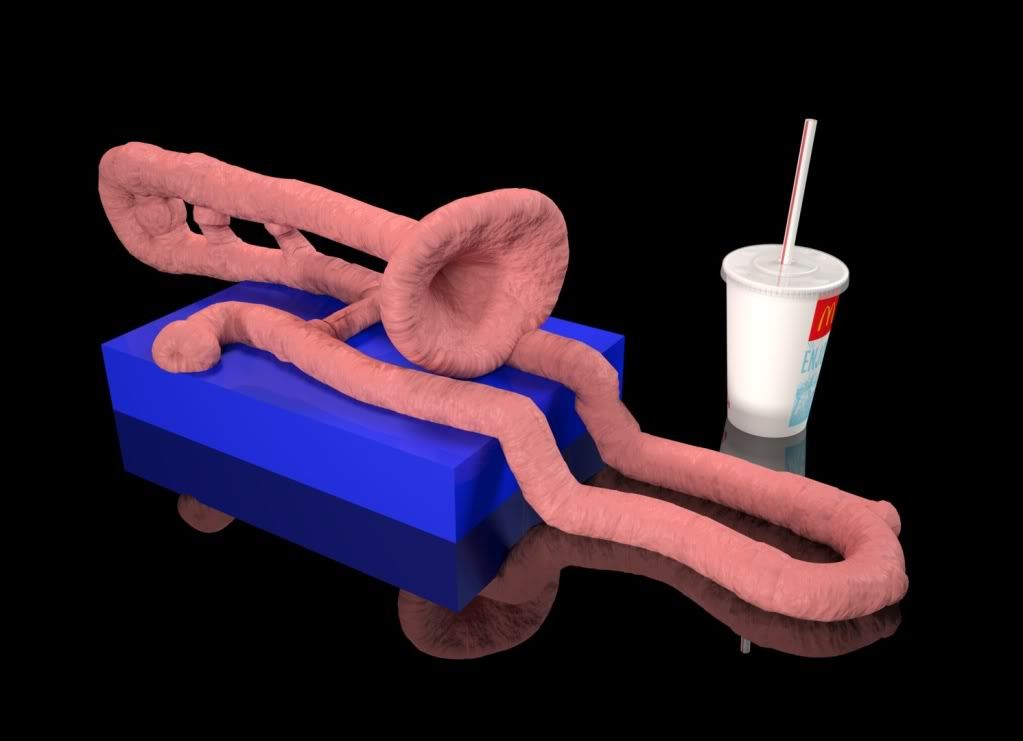

Takeshi Murata, Gumbone and Coke, 2011

Takeshi Murata, Gumbone and Coke, 2011

In addition to

Oh, Wicked Wanda!,

Kramer's Ergot deviates from purely contemporary comics by including a portfolio of digitally altered photographic work by

Takeshi Murata, an American artist working in video, photography and digital art. Aside from the striking quality of Murata's images, his inclusion may have been a statement about

Kramer's Ergot context. It says that this is a comics publication with strong leanings towards contemporary visual art. That is also implied by the introduction, which discusses art history. I advise readers to skip it--it's a string of cliches and misinformation, and doesn't speak to the work that follows it.

I'm still trying to understand the work of the Art School Generation. That's one reason I wrote this review, to think through their work and its implications. As difficult as much of this work is,

Kramer's Ergot remains a key publication in the broader world of art comics and for the Art School Generation.