When I think of the work of Jules Olitski (whose work is currently on view at the MFAH in an exhibition called Revelation: Major Paintings by Jules Olitski up through May 6), I think of works like Monkey Woman (1962)--blobs of color soaked into unprimed canvas. This is the Olitski of art history as we generally think of it. (That standard history might go like this: Modernism begins in the late 19th century. It moves unevenly through the 20th century to greater and greater levels of abstraction and essentialism, reaching a conceptual dead end in the early 60s, at which time post-modernism's anti-essentialist, anti-Kantian, theatrical approaches take over.) Olitski is an exemplar of the late modernist idea that a painting's essential qualities are arrangement of colors and flatness.

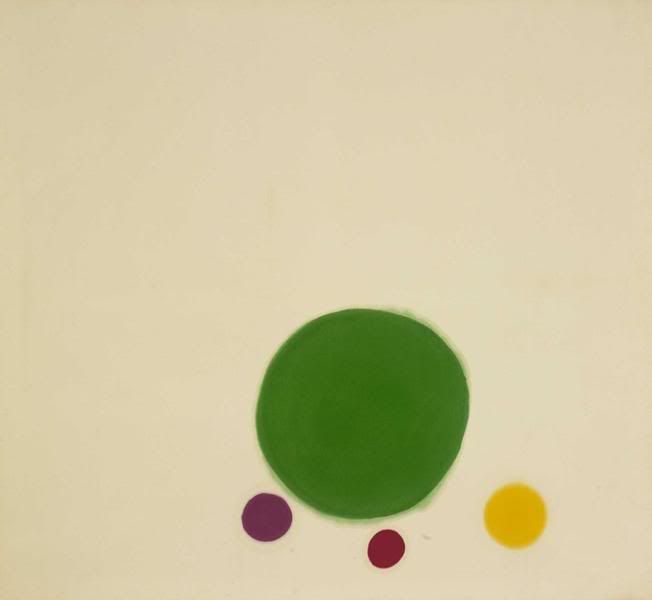

Jules Olitski, Monkey Woman, 1964, acrylic on canvas

The thing is, Olitski just ignored that grand art historical narrative. He quickly gave up "flatness" (some of his later paintings are so heavily impastoed that I worried that the weight of the paint would tear the enormous canvases).

The museum has a whole wall of his late paintings (Olitski died in 2007 at age 84). Before I saw this show, a painter friend of mine who had seen it characterized these paintings as "fraught." I wondered what he meant until I saw them. The word I would have used was "anxious," but we're close enough.

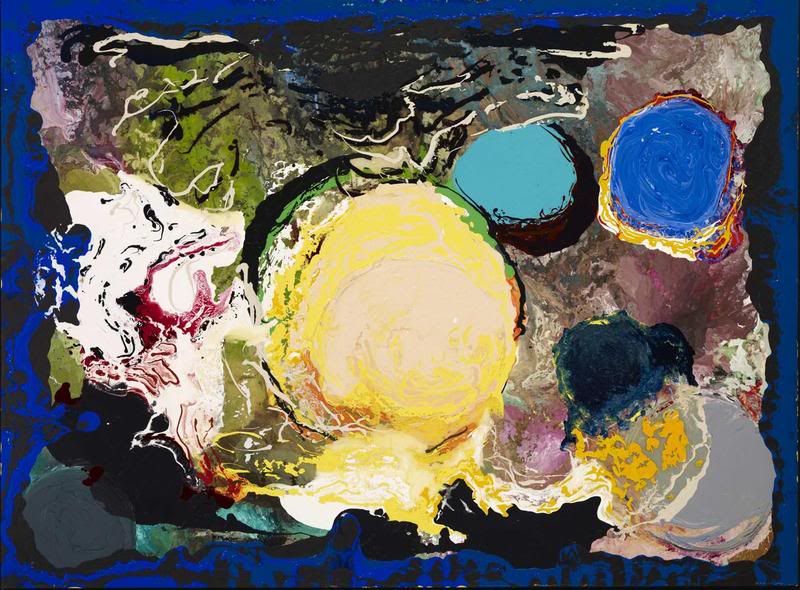

Jules Olitski, With Love and Disregard: Splendor, 2002, acrylic on canvas

As you can see in With Love and Disregard: Splendor, he poured paint onto the canvas. This was the technique used in all the the late paintings displayed at the MFAH. We see big round blobs of color, but we also see shaky strings of paint on the edges of each blob. The jittery quality of these lines is one reason they pictures feel anxious to me. Another reason is the craquelure--the "cracks" that are visible in some of the round blobs (not so much in this painting, but in some of the other late paintings in the show). This effect can be deliberately induced. For example,you can induce cracks by putting a fast-drying paint on top of a slow drying paint (different color paints dry at different rates). I assume Olitski did this deliberately, but who knows for sure. In any case, the jagged cracks contribute to the anxious surface.

This is an artist who spent a lifetime creating works that largely washed over the viewer with gentle waves of color. Why at the end of his life are his paintings so different? Was it a fear of death, or new anxiety about the world (these were painted post 9/11). Or were these jagged, shaky marks the way he painted for physical reasons (perhaps he had Parkinson's, or perhaps age alone made it harder for him to hold a brush steady). Or possibly, these were just formal moves by Olitski, without connection to the artist's mind or body or the state of the world. It could be any of these things, I suppose. Whatever the reason, it is interesting to see how an artist you think you know changes over the course of his life.

No comments:

Post a Comment