Along with universal literacy and free healthcare, one of the blessings of communism in Cuba, party members assert, is exceptional sports education that makes possible highly paid professional athletic careers and even the possibility of Olympic medals. Such gifts are offset of course by appalling poverty that forces much of the population to survive on a few dollars a day, a medieval transportation system, a repressive regime of old farts who imprison political dissidents and restrict speech, assembly and movement.

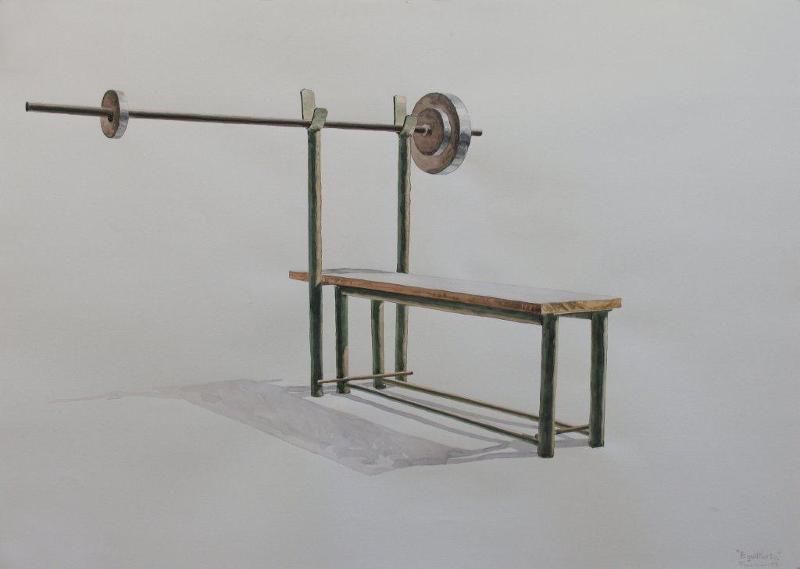

Cuban artist Franklin Alvarez told me that Cuba’s fitness obsession reaches beyond the educational system. So desired are bulked up muscles, desperately poor people improvise bar bell and weight gyms outside with their chickens and pigs. Franklin made Cuban fitness an important theme in his art. He paints in the watercolor Equilibrio an antiquated weight bench with mismatched weights to reference body building as well as societal disharmony.

Franklin Alvarez, Equilibrio, 2001, Watercolor on Paper, 29.5” x 41.25”

The fitness theme surfaces repeatedly, and is dealt with comically in the painting in which Van Gogh’s face appears on a body builder whose chicken and pig repose near his weights, an art historical invocation with attendant commentary on Cuban deprivation. In the same vein, a sculpture Franklin exhibited in a recent Biennial was comprised of a diving board positioned above trash cans instead of a pool to symbolize Cubans who dig in the trash for food.

When I saw fancy trays of spring rolls and a proper bartender refilling glasses, I knew it was a special event. Redbud Gallery had invited collectors, other artists, and friends to meet Franklin Alvarez and preview “Weightless,” his exhibition of paintings scheduled to open a few nights later. The reason the evening was special was because, although this distinguished artist had exhibited in Europe, South America, the Middle East, and here in the U.S., he had never before been in the U. S.

Redbud’s Gus Kopriva was away in Kuwait or somewhere, so Sharon Kopriva performed hostess duties such as organizing the preview reception and dinner at a Vietnamese restaurant, but fortunately she had some help. Art Guy Jack Massing participated in the hosting. I overheard one artist not entirely comfortable with conversation greet the Cuban, “Oh Hi. Jack told me I had to come.”

Franklin Alvarez traveled from Cuba for his exhibition at Redbud Gallery – photo by Virginia Billeaud Anderson

So with my pathetic Spanish and his limited English, Franklin and I began over the course of several visits to become acquainted. One of the first things he asked me while he enjoyed a bowl of Sharon’s fruit soaked in vodka was did Louisiana have water. As I began to explain the Gulf of Mexico he quickly remembered his geography, and after asking if post-Katrina New Orleans had been rebuilt (yes, not everything - many people died) he found it regrettable that some Americans lived in land locked states.

Water has metaphorical import in Franklin’s art. In the 2002 painting Se Permuta (For Exchange) figures run along a riverbank pulling a boat with ropes, an allusion to Cubans drowned in immigration. For Se Permuta, he borrowed the composition of Russian realist painter Ilya Repin’s 1873 Barge Haulers on the Volga. It pleased him to appropriate from Repin he told me because of Repin’s narrative penetration of tensions within Russian society, and also because he desired to pay homage to a masterful painter who was little known in Western art history.

I had always heard that the Cuban government forbade citizens to leave, and that many were killed trying to escape, that like at the Berlin Wall, Cubans killed other Cubans for trying to escape. How was he able to come here? “It wasn’t easy,” he said. He needed to obtain special permission from the Cuban government, first needed two official invitations, and a U.S. visa. It was uncertain he would be able to come. “Leaving is easier now than it used to be,” Franklin clarified, and “it is easier for artists than for others.”

Trying to imagine my own travel being restricted, I wanted to punch someone on his behalf, and wondered if he went through life particularly cognizant of his liberties being curtailed. Only in the realm of free expression, he explained. When he was younger he saw the government cancel art exhibitions it deemed hostile. “Things became looser in the last years of Fidel, and now with Raul. The government became more relaxed in the sphere of culture because it wants to be connected to culture. Artists have the ability to speak politically through metaphors.”

According to Franklin some artists make direct political attacks in order to be censored, and gain more attention. His art reaches beyond the political, he stressed, to emotions and psychology. “My art addresses the political, social, and personal. It is a more philosophical approach, more universal.”

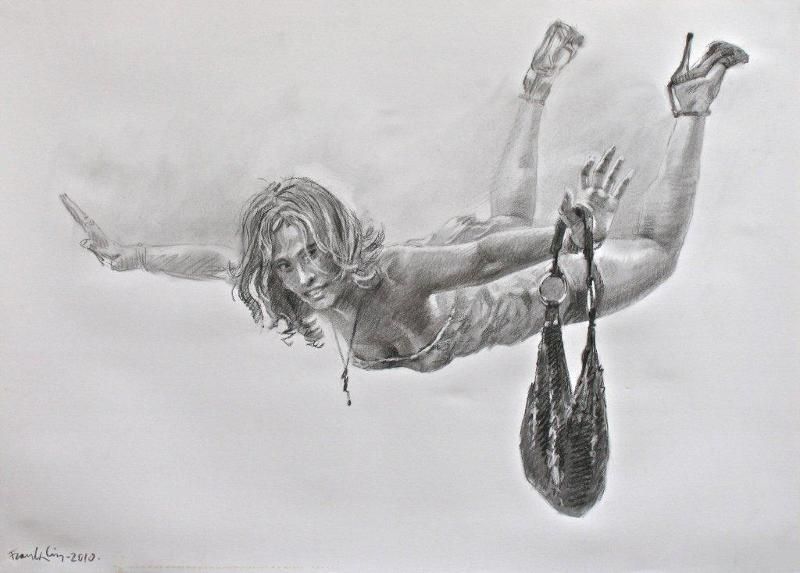

Franklin Alvarez, Flotando, 2011, Watercolor on paper, 29.5” x 41.25”

It is easy to recognize academic training in Franklin’s art. His handling has the linear refinement of Ingres. The artist studied at the prestigious Instituto Superior de Arte. How did he get educated? All of his education came from the government, he told me. He began studying art when he was 12 years old, and studied for twelve years. He was a professor of art for three.

Franklin explained that the Cuban government values art education and artists because these things demonstrate that even a poor person can manage to become prominent. Were you poor? “Yes, everyone is poor. There is no middle class.”

“Artists in Cuba make more money than doctors,” he said.

What art were you aware of when you were developing, at whom were you looking? “Picasso, Da Vinci, Matisse.” Did you know Lam? “Everyone in Cuba knows Lam. Wifredo Lam is the Picasso for Cubans.”

At one point he observed that Houston’s economy was “strong” and asked if it was due to oil & gas. What precisely evidenced for him our strong economy, I wondered, what specifically did he notice, ridiculously high gallery prices? It was the architecture he said, and “the educational and cultural level of the people,” which he found elevated compared to Cuba.

Lynet McDonald, Redbud’s gallery director, told me it was a satisfying experience to drive and accompany. In the supermarket he was overwhelmed by so many choices, and he just about lost his composure when he saw a car dealership. So many new cars! In Cuba he told her the cars are old.

Franklin Alvarez, Torre, 2007, Acrylic on Canvas, 19.5” x 23.5”

It’s shocking to recall that Cuba’s tumultuous changes took place when I was a kid. In 1958 Batista fled and by 1960 Fidel had established a dictatorship with firing squads, collectivization, and a silenced press. Cubans with money hauled ass. Fidel’s intention was to emulate Lenin, Stalin and Mao, so I went back to Marx to try to grasp the ideology. “In advanced countries,” The Communist Manifesto states, “the following will apply: abolition of property ownership and application of rents of property to public purposes, a heavy progressive or graduated income tax, abolition of all right of inheritance, confiscation of the property of emigrants and rebels, centralization of credit in the hands of the State, centralization of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State, free public education, etc.”

On June 2, the day of Franklin’s exhibition opening, President Raul celebrated his 81st birthday and was, the media reported, “racing against time to reform Cuba's economy to try to assure the survival of communism after he and his elderly colleagues are gone.” Fidel is 85, feeble, and hidden, his two closest communist hardliner cronies are 80 and 81.

When the old goats die, enormous changes might occur. Even though there is crippling debt and subsidies have significantly diminished since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Chavez’s oil and money contributions will probably be short lived, today Cubans dabble in free enterprise businesses, and own cars and homes, and the U.S. might lift the embargo. Most significantly, Cubans travel and have the internet. Franklin is aware of the possibility of profound transformation. The free falling and floating figures he paints narrate dream-like respite from hardship, and emblemize Cuba’s unknown future.

Franklin Alvarez, Torre, 2004, Oil on Canvas, 23.75” x 15.75”

What does he desire for his career? “To find more U.S. gallery representation,” Franklin said. He handed me a portfolio disc and suggested I help him.

What does he think of Houston hospitality? Big grin - “It’s been excellent. So good, I am very happy.”

Did he enjoy the Vietnamese food? “Yes.” (I’m not convinced.)

What else did he eat? Another big grin, Mexican food, twice. “Jack took me.”

What was his favorite meal? “Berryhills!”

No comments:

Post a Comment