Two recent news stories got me thinking about how politics colors people's vision of art, especially people from outside the art world. (Not that politics isn't important inside the art world, but our politics are often so parochial that to outsiders they may appear meaningless.) First was the story U.S. District Judge Vanessa Gilmore who was offended by a painting by Alexandre Hogue, The Diana Docking reported in The Houston Press.

Alexandre Hogue, The Diana Docking, 1941

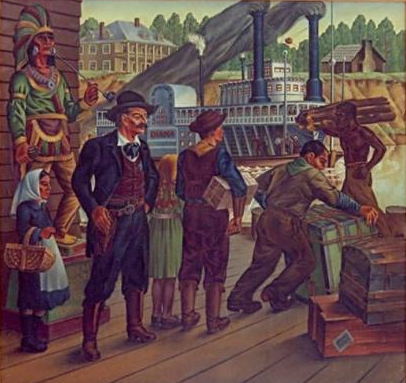

Alexandre Hogue was a Dallas painter who worked in a social realist style. A lot of his works were dust bowl farm landscapes--the absence of people in them was a powerful message of the ravages of drought on poor farmers during the 30s. He and fellow painter Jerry Bywaters painted a mural series depicting the history of the Houston Ship Channel for a Post Office building here in Houston in 1941. They were removed sometime in the late 50s and early 60s (possibly because of their pro-labor messages) and then rediscovered in 1975. They were then installed in the Federal Court Building.

Gilmore's objection is to the depiction of the shirtless black man. She states

I brought a boy scout troop here over the holidays to earn their citizenship badge and while I was very proud to show them the historical time line with information about our court, it was rather awkward to have to walk them past the old, antiquated murals with pictures of shirtless black men hauling wood and bales of cotton. It said nothing about our court except that maybe we are too insensitive or oblivious to let some of these images die. We finally managed to get these dreadful images out of the lobby. Now can we please retire them for good. ('Some Judges Want Paintings of "Shirtless Black Men Hauling...Bales of Cotton" Removed from Courthouse,' The Houston Press, February 9, 2012)I can understand her discomfort, but on the other hand, it's a true depiction. Ironically, these murals were progressive at the time they were painted. In this way, it's a little like the controversy about Nigger Jim from Huckleberry Finn. Huckleberry Finn is notable because of the humanity it gives to Jim, but now it is difficult to teach because of the word "nigger." I am opposed to bowdlerization, but I understand why the issue exists. (Another judge, Kieth Ellison, added that he shared Gilmore's concerns but also felt that the murals are "bad art." I can't say I agree with him since I haven't seen all of the murals, but The Diana Docking is a really awkward painting. It's not a good example of Hogue's work. Google it and you'll see what I'm talking about.)

But even if Judges Gilmore and Ellison have a point, I can't help but be reminded of the Maine labor mural controversy. In 2011, the governor of Maine, Paul LePage, ordered the removal of a mural from the lobby of the Department of Labor. LePage was elected as part of the Tea Party wave of ultraconservative politicians who gained office in 2010.

Judy Taylor, Maine Department of Labor Mural panels 1-3, paint on MDO board, 8' x 12' (this section)

Judy Taylor's 2007 mural depicted the history of the labor movement positively, which conflicts with LePage's views. LePage's political perspective is probably quite a bit different from Ellison's and Gilmore's. But if Gilmore succeeds in getting the Hogue and Bywater murals removed, what she will share politically with LePage is censorship. And whether you agree with the censorship in either case probably will have something to do with your political perspective.

A recent piece in the Art Newspaper shows what happens when this attitude spreads. The new right-wing government of Hungary has pushed through a new constitution that many consider anti-democratic. In addition to this and many other alarming actions the government has taken, it is asserting itself in the aesthetic realm.

Last month, to celebrate the official inauguration of the constitution, [Prime Minister Viktor] Orban opened a government-organised exhibition at the National Gallery. It chronicles 1,000 years of Hungarian history, focusing on sovereign statehood and Christianity (until 16 August). The show includes 15 large state-commissioned canvases depicting important historic events spanning 150 years, including an image of Orban. ("Hungary's Government Tightens the Grip on Arts," The Art Newspaper, February 9, 2012)This kind of outright propaganda is a little disturbing, although most governments engage in this kind of thing to one degree or another. But combine this with acts of censorship, and you start to have the artistic signs of authoritarianism.

A row broke out in March last year over an image of Hungary’s interwar leader, Miklos Horthy, at the Holocaust Memorial Centre. The state secretary, Andras Levente Gal, said that the picture unjustifiably linked Hungary to the deportation of Jews to Nazi concentration camps and asked that the display be “re-evaluated”. “This kind of historical inaccuracy creates unnecessary tension,” Gal said. His remarks prompted an outcry among some historians and the liberal press. Matters deteriorated when the government relieved Laszlo Harsanyi, the director of the centre, and his chief historical adviser, Judit Molnar, of their positions. ("Hungary's Government Tightens the Grip on Arts," The Art Newspaper, February 9, 2012)(Hungary had a pro-German government throughout most of World War II, but Hungary'santisemitic fascist movement, The Arrow Cross, was outlawed. Germany fell out with the government of Hungary in 1944 and invaded. Arrow Cross was legalized and put in charge of Budapest, where they were able to aid in the deportation of 400,000 Hungarian Jews to the German extermination camps. The participation in this deportation of members of the Hungarian government and police forces is a historical fact. However, Horthy largely prevented deportations from happening as long as he was President.)

As soon as an artist takes an art commission from a government, she sets her art up to be judged politically--and that judgment may happen long after she have departed the scene. People with political power often have underdeveloped beliefs regarding openness and freedom. individual instances of censorship increase as political winds change. But when the political winds shift towards the authoritarian or fascist, as they appear to be doing in Hungary, art as a whole becomes a tool of the state.

I wonder what a contemporary, realist painting of the dock would look like. Or for that matter, the courthouse. Would it be terribly dissimilar? How about the county jail? There's an offensive image.

ReplyDeleteWell, remember that the Hogue paintings were historical even at the time they were painted. "The Diana Docking" was meant to be an antebellum scene (I assume based on the paddle-wheel boat in the background). So yeah, a contemporary painting would be quite dissimilar--no half-naked slave stevedores, for one thing!

ReplyDeleteArt Removal? Such a strange argument to make. I'm not sure I want to wind up in a court where the best narrative a federal diva judge can create for a WPA painting is "racism." While probably not a top-ten Hogue, there are nuances worth exploring: the lawman, the black laborer--post slavery, indian reduced to a wood statue. I'd speculate Hogue developed the scene to elaborate injustices, not celebrate them.

ReplyDeletePerhaps the church-going-Judge Judy would recommend removing the barbaric bloody cross behind the christian dais; no sense in reliving those gruesome events a couple millennia ago.