In 1985, some grad students in the U.H. art program were about to be kicked out. Their crime? They had completed their degree requirements and were graduating. They had studios at Lawndale, an off-campus site where the UH art department moved to after its on-campus building was damaged in a fire. It had been acting as the U.H.’s art department’s home since 1979. It was an enormous former factory and provided studio space for many of Houston’s best young artists as well performance space. (The story of Lawndale’s rise and triumph is told in Collision by Pete Gershon.) A couple of these art students, Kevin Cunningham and Wes Hicks decided to take their impending eviction and to try to recreate the Lawndale experience. They found a new ex-factory and established an art center containing studios and a large performance space. For legal reasons, it ended up with the name Commerce Street Artists Warehouse, or CSAW for short. In 2016, I interviewed several of the early residents of CSAW. I have finally gotten around to transcribing some of them and editing them.

Hicks is a painter. He grew up in Indonesia, studied art at the University of Houston, co-founded Commerce Street, and lived there until he was evicted in early 1994. While he was there, he ran the punk rock club, Catal Huyuk. This is kind of a long interview, so I am going to split it into several parts. Below is part 1 of my interview with Wes Hicks. In part 2, we’ll discuss some of the people who had studios or hung out at CSAW. The photos included come from various sources and I have tried to identify the source if I know it.If anyone knows where a given photo is from, please let me know!

ROBERT BOYD: You were a student at UH. Is that correct?

WES HICKS: Yeah, I was a student at the University of Houston, and which at the time was mainly Lawndale if you were a painting or sculpture student. We thought of ourselves as students of Lawndale University more than anything.

BOYD: My understanding is that you guys wanted to find someplace that had a similar feel to Lawndale, but that you ran yourself.

HICKS: Well, that was kind of it. Basically, what happened was we were all kind of getting booted out of Lawndale because we'd finished as many of the courses you could take there. They needed us to move along. Because we were seniors or graduate students who finished the program. Of course, we just wanted to stay on, but Gael Stack who was in charge said, "OK, this is your last semester here." I thought the idea was to organize a lot of the Lawndale friends that I had to start a communal art space in the warehouse district, emulating what all Lawndale was but with just us going it alone.

BOYD: How did you find the Commerce Street location?

HICKS: Kevin Cunningham did that. What happened was that all our friends kind of peeled off because basically they thought we were crazy. Except for me and Kevin Cunningham. Kevin knew Lee Benner through the skate scene, the Urban Animals. He took me to a party there in the building at Commerce Street, which at the time was just one big huge empty room with a lot of water on the floor, no lights or electricity, all the Urban Animals were skating around. That's how we kind of found it. We talked to Lee Benner; he knew the landlord because the landlord was Lee Benner's landlord. We just kind of went from there, one step at a time.

BOYD: When you found it, it was you, Kevin Cunningham, Deborah Moore. Rick Lowe was there at the very beginning, right?

HICKS: No, he wasn't. It was basically me, Deborah, Kevin and Jane--Jane Ludham--she was like a support team for Kevin. Then Jackie Harris and Steve Wellman and all those people were just kind of hanging around but no one would commit, so the whole thing looked like it was going to fall apart, then people just started showing up out of the woodwork, like Dr. Robert Campbell, then Rick Lowe. He was in very early on. We had to form a corporation because the landlord couldn't imagine signing a building without a corporate lease back in those days. We had to form a corporation, which as you know is really easy in Texas. Just 250 bucks and you drive to Austin. I think it was me, Robert Campbell, Kevin, Deborah, and Rick Lowe were the original corporate shareholders. We owned the thing, but none of that mattered. It was just for the landlord.

BOYD: So that's where those five names came from--they were on the paperwork, basically.

HICKS: Yeah, and we did have a structure where we would have votes and decide what we were gonna do. There were five of us, so if three voted one way and two voted the other. But we all agreed on everything pretty much. The big thing was about a third of the building in the back.

That was the big thing for me was the performance bay; it's almost a third of the building. It's a big huge empty room with really high ceilings and giant skylights, a massive entrance so that a huge crane could go in and out through giant steel doors. It's just this incredibly beautiful, almost perfectly square space. A little rectilinear with these giant pillars. I really wanted to keep that a communal performance bay that was open to anyone--not just us--that came to us with a good idea. We were going to do shows there regardless of quality or ideological baggage in the sense of "This is our art style--we don't like your art style." It's just going to be open to the public pretty much. I had to constantly fight for that. I think Deborah was pretty much on my side. This was always a bone of contention. Because she could have rented the space out and made all the rents much cheaper.

BOYD: Put up some walls and made some studios.

HICKS: Exactly. From the very beginning I was challenged. Jackie Harris wanted to use the space for her art cars. Make it into a giant art car development thing. From the very beginning, this was the big battle. I think that if I had lost and it had been developed into studios, then Commerce Street wouldn't have been Commerce Street.

BOYD: Kevin Cunningham made a really good point--you give a bunch of artists who are used to working in studios 27,000 square feet, suddenly doing a painting isn't enough. You have to fill that space somehow, and filling that space meant having a party or having an exhibition or having a performance of some kind.

HICKS: Yeah. In essence, that is what Lawndale was. Lawndale had a huge performance bay that was run by crazy, out-there people. First James Surls and then Chuck Dougan then Moira Kelly. And they always brought in really cutting-edge stuff that blew away the whole Houston art scene from Philip Glass doing operas early on; Moira Kelly having the Replacements come and really crazy bands that became famous later played Lawndale. The students were the stagehands, the volunteers who did all the work. That's where we go kind of like an apprenticeship. By the time we were starting Commerce Street, Kevin and I pretty felt like, hey, we can do this ourselves. Because we had learned from Moira Kelly and Dougan and James Surls and everyone how to it, and had worked with people who were masters of their craft on Philip Glass and stuff like that. And even if we didn't actually work with these people --have you ever heard of the band Sun Ra?

BOYD: Yeah.

HICKS: They played at Lawndale a lot, and I just kind of hung around with them and we just absorbed this stuff, as a really young person talking to the Sun Ra guys and telling us how it all goes down and what to do and the lives and touring. It was just a mind-blowing experience. When we had to leave Lawndale, we wanted that. Also, the economic situation in Houston at the time was almost impossible to imagine nowadays. The warehouse district was an abandoned wilderness. Literally a wilderness.

We were surrounded by abandoned warehouses. At that time, they hadn't all started to burn down. In the late 80s, people started to burn warehouses down for insurance money. Also, it was the deindustrializtion of the United States going on. The warehouse we were in was used by Westinghouse to build giant electric motors for ships. That had been gone for like 20-30 years by the time we got there.

[Commerce Street] was a totally black building. No lights. Rubbish in the front. All the toilets were rubbished. Homeless people had been crashing there. It was full of water because the ceilings were leaking. In the very back where Dr. Robert Campbell decided to build his space the roof was collapsed in an area of about 8 by 10 feet. And underneath that, plants were growing. So it was like a cave. In the daytime the sun would shine in. Actually, it was really beautiful. Pigeons and bats were living in there. It was just completely wild.

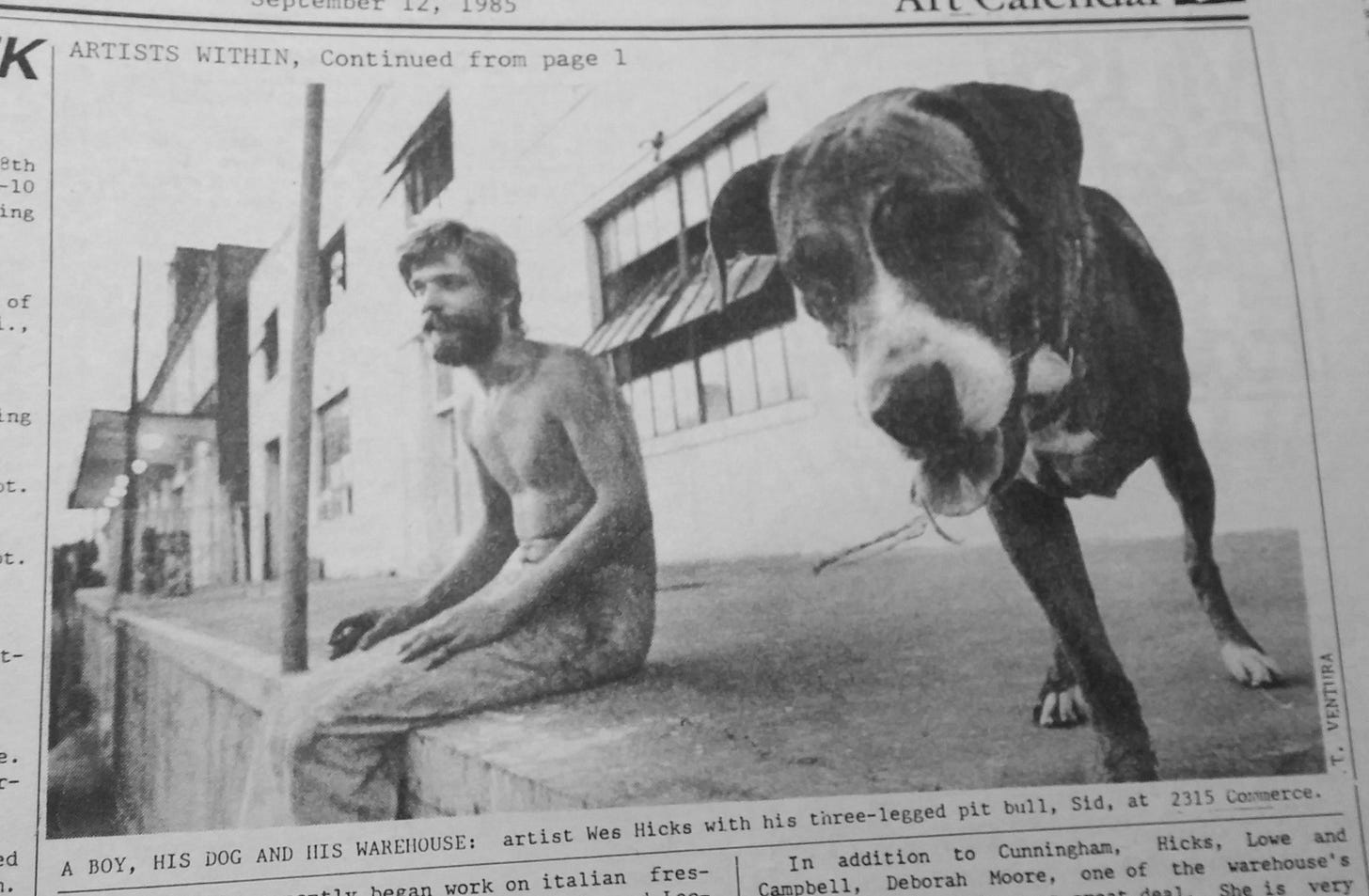

A photo from the late, lamented Public News in 1985. Photo by T. Ventura.BOYD: What did you have to do to make it habitable?

HICKS: Well, first we had to get permission from the landlord. And then we just started cleaning up. We made a deal with the landlord that she'd get an electric box for the front of the building. She'd bring the electricity to the building, and she would fix the roof. And once that was done, we'd start paying rent to the tune of I believe $1800 or $2000 a month. Which works out to about 14 cents per square foot, I think if I've got my numbers right. So that's what she did and that's how it started. We had this kind of very tenuous situation with the city, where the fire marshals were coming over and letting us do things that were plumbing and electrical ourselves, as long as we got electricians to come check it and make sure it was all done right. It was kind of an interesting relationship we had with the city.

Because of Houston's laissez faire no-zoning thing, they were willing to let us do really crazy stuff. They were shaking their heads--the fire marshal people. And they did weird things, too. Like one time, we were gonna do a huge benefit for the South Texas Nuclear protest project, because they were gonna build a nuclear plant in South Texas on Padre Island or some place. All these bands were going to play there and do a fundraiser for the protesters. The fire marshal came around and wrote me something like 13 citations for violations, and I knew this guy. He said, you know, if you're open tonight, I'm going to come here and arrest you; then he goes, if you're not open tonight, I'm just going to tear up these citations and we can just forget this ever happened.

BOYD: So what did y'all do?

HICKS: Oh, we weren't open that night. We told the 13 bands or however many there were that the show was shut down, which sucked ass. I can't go to jail and shut down this space. That was the end of that. But they actually moved it to another warehouse space. Some artist who apparently weren't aware of the situation. The fire marshal came there and arrested them and shut down their space. We were always at the mercy of the cops and the fire marshals who made it very clear to me that we existed only because they wanted this.

I don't think the cops really cared too much or the fire marshals cared too much about whether those buildings burned down or not. That was one of the things about Commerce Street, in relationship to the fire marshals and the Axiom, too. Because the way they were set up, you couldn't actually have a fire like those nightclub fires where 200 people died in Brazil and stuff. That couldn't happen in these places because there were all these giant exit doors that were open. Because it was so hot in Houston. People could just stampede out in a fire scenario.

BOYD: Once you started building it out as a studio space, at first it was just one big open space, right? How quickly did you guys build up walls and stuff.

HICKS: Well, actually it was two big open spaces. The back part of the building (the performance bay) was the original Westinghouse warehouse that was built in the 1920s or maybe even earlier. It was all wood with giant cypress posts that were like 18 inches by 18 inches, holding up a giant wooden ceiling. And that's now been demolished and taken away. It's a car park. And then the front of the building was added for war effort for World War II to build electric motors for the Victory Ships.

BOYD: The ones that were turned out pretty quickly for Great Britain.

HICKS: Yeah, exactly. They were making these giant motors there--these huge electric motors that weighed many tons. That's why the foundation of Commerce Street was this big, huge six-foot concrete block. It was because they had many tons of electric motors. It was two giant buildings and there was a wall between them with two big doors. We started almost immediately building walls. People that wanted them. That was totally individual. Some of the earliest complete studios were Dr. Robert Campbell--built his out pretty quick. He picked one of the worst corners of the building to build in. His walls in the back had to be 20 feet high. I don't know how high the ceiling was. More than two layers of sheet rock. So yeah, like 18 to 20 feet tall. And John Calloway built a big studio back there. Jack Massing built a little studio in the back space. And up front we decided where the corridor was going to be, and because of the way the steel beam structure was and the ceiling and the beams. You could kind of see how each space was going to be this rectangle, 1200 square foot. Like 30 ft by 40 ft. We designated all the studio spaces and when you moved in (all the early people), you either hired somebody or you built walls.

BOYD: People lived somewhat in their studios, right? Some did.

HICKS: A lot of people did. Most of the really hard-core artists did because they were young and that's what they had to do. But then about half the people didn't.

BOYD: Did you live in the studio?

HICKS: Yeah, I lived upstairs. There was a front office part of the building--that's where the toilets were and kind of an entrance foyer, and then there was an upstairs. It must have been the executive offices. And that was a big brick building with hardwood floors that were painted over. We put two studios up there and one of them was mine and the other--it may have been Nestor Topchy and Rick Lowe were the first people to occupy that space upstairs. Nestor and Rick were living upstairs with me, opposite in offices. They were in the western wing and I was in the eastern wing.

Another shot from the Public News by T. Ventura. Wes Hicks (left) and Sid the dog (right)

BOYD: What happened in the Performance Bay?

HICKS: The Performance Bay was mostly performances. But then, I gave myself a show there. Mike Scranton had a huge show there. Nestor had a huge big show there. It lent itself really well to big sculptures, like Nestor's spheres, Mike Scranton's dinosaurs. We did hang art on the walls, too. There was a long hallway. There's a long hallway that goes down to the front. We would hang art all the way down that hallway. Perry Webb's gallery could also be filled with art. It was more intimate and small. Also, more delicate because you could actually lock that room up. If something like prints that were more valuable, framed with glass or something, you could lock those up. At this time the building was open to the street 24/7. Nothing really ever happened, but in the middle of the night, drunk people could run up and down the hallway and knock art off the walls. People could ride motorcycles through the building. That’s what Perry Webb provided us with—an art space that looked like a traditional art gallery. It didn't operate like a traditional art gallery. A lot of times we hung art salon style. But I think all the best shows there were not art shows of paintings. Some of them were maybe sculpture shows. But they were soundscape, industrial music, performance; those were the shows that really captured the spirit of the age and the space and the part of the city we were in better than anything, in my view. Things like Crash Worship-- I think they played two shows there. Have you ever heard of them?

BOYD: No.

HICKS: They were a San Francisco drumming group that would just work up the crowd into a trance, and everybody just starts jumping up and down, lighting fires, and then they just move around the building and break out into the street, this whole crowd becomes incredibly tribal. And they had a huge following in Houston. So 300, 400, 500 people would show up for their shows, and form this big, huge hopping mob. People would pass out and go into speaking in tongues. Things like that were real shamanistic in a way. Real connected with the wilderness aspect. We were in an urban wilderness.

This is Crash Worship playing at The Abyss in Houston in 1997.

BOYD: Back then, streets like Commerce St. didn't have tons of traffic.

HICKS: In the middle of the night there was no traffic. Really after 6 o'clock at night the traffic died down to zero. Also, Commerce St. at that time was six or seven lanes wide. Two or three hundred dancing down the street, half naked, lighting fires and drumming didn't bother anybody. No one would call the police on them. And the police, if they showed up, they'd just watch. It was a wilderness area, an urban wilderness. The warehouses were abandoned around us. People from HSPVA--there was a group of them that would come out to our shows. This is like 86 or 87. And they would do stuff like drop acid and climb around these abandoned warehouses. I was always a bit concerned for them because they went into places that were pretty scary in the dark. In the full moon. We did crazy thing. It was a true wilderness--you could do anything you wanted.

It was an urban wilderness--not like a national park wilderness. We had these industrial music bands like Voice of Eye--have you ever heard of them?

BOYD: No, I haven't.

HICKS: Jim Wilson was one of the founders of Voice of Eye with his girlfriend Bonny. They pioneered a lot of that industrial music in Houston and played at Commerce Street maybe a hundred times. Often to crowds of 10. [laughter] But it didn't matter--it really didn't. Also with the acoustics of the Performance Bay--four people doing industrial, abstract sound--was also incredibly romantic. I felt really connected to the romantic artists of the 17th century. All that crazy stuff.

No comments:

Post a Comment