by Robert Boyd

A big piece of news in the art world this week was the summary dismissal of

Paul Schimmel from

MoCA in Los Angeles (some MoCA board members

insist he resigned). He was MoCA's chief curator for over 20 years. One of Schimmel's first shows was

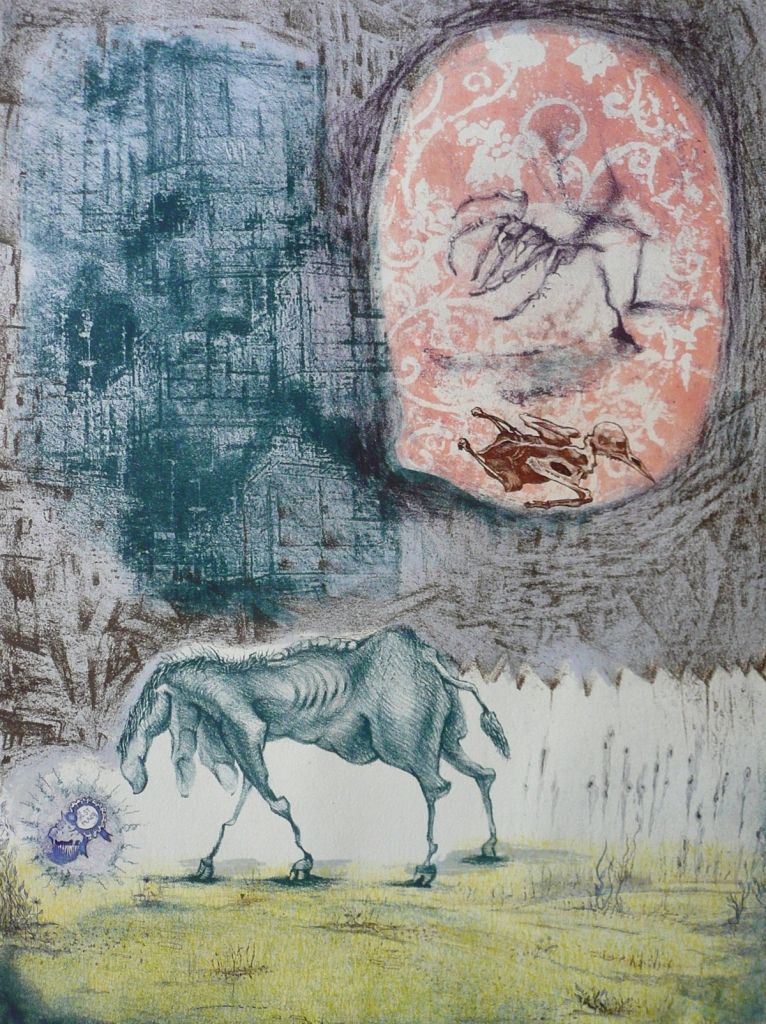

Helter Skelter in 1992, a group show that was generally panned at the time but in retrospect seems very important. Personally, I loved

Helter Skelter. When

Misfit Lit, a show of alternative comics that I helped to curate, went to

LACE, I flew down from Seattle with Larry Reid and Pat Moriarity to help install it. While we were in LA, we went to see

Helter Skelter at the big Temporary Contemporary building (now permanent, it is called the Geffen Contemporary). At the time, what got to me was how dirty the show was--

Paul McCarthy's robotic mannequins fucking trees!

Robert Williams' paintings full of tits and ass! But in retrospect--and very influentially from my point of view--was that it combined very grungy aspects of performance and conceptualism with figurative "low brow" art, and the combination

worked beautifully.

Schimmel (who

was a curator at the

CAMH in Houston in the late 70s) was at MoCA for 20 years, so he must have been doing something right. So what happened? Here's how

Mat Gleason described events:

Paul Schimmel was fired at MOCA - it was the end of the fiscal year and they tightened the belt. It is easier to have a corporate sponsor pay a guest celebrity curator - the curating has been outsourced.

The design department is outsourced to Sheppard Fairey’s design company, the education department gets grants and therefore competes with the Board for power so people there are being hacked away left and right, but the cutting off of Schimmel is a bold move by the Jeffrey Deitch/Eli Broad consortium to advance the outsourced party time event based museum that will not function as a repository of great art but of great parties.

If Moca is downsized into a celebrity-curated kunsthalle style circus, it will give the blue chip Broad across the street more Gravitas. And then of course when MOCA is broke yet again - who will save MOCA by purchasing the best paintings in the collection because the museum is more concerned with event programming? The Broad Museum across the street of course. [Mat Gleason, "MOCA Fires Curator Paul Schimmel," Coagula, 6/27/2012]

Eli Broad is being fingered as the evil mastermind, with Deitch as his hatchet man.

Art Fag City lends some credence to this theory by pointing out Broad's recent involvement with MoCA.

According to the email, Schimmel was let go in conjunction with a number of curatorial assistants and other employees. This news comes just four years after wealthy benefactor Eli Broad pledged to donate up to $30 million over five years to the museum with “the expectation that the museum’s board and others join in this effort to solve the institution’s financial problems.” At the time, it was hailed as “the billionaire’s bailout” for the museum, which suffered losses in investments due to the stock market crash. Broad will match contributions to the endowment up to $15 million, and make annual donations of $3 million earmarked for exhibition support. ["Why Would MoCA Fire Chief Curator Paul Schimmel?", Art Fag City, June 28, 2012]

But if Broad was set on taking over MOCA or acquiring some of its best work for his own museum, how would Schimmel pose a problem? AFC suggests the issue was animosity between Schimmel and Deitch.

Reporters have cited the acrimonious relationship between MoCA’s new Director Jeffrey Deitch and Chief Curator Paul Schimmel as a possible cause for dismissal. The LA Times’s Christopher Knight wrote over Twitter this morning that “[t]ensions had been brewing for a long time.”

This March, The LA Times reported that key financial personnel left the museum. Should personality conflict have been an issue, it would not surprise many. Schimmel is widely respected for exhaustive, thought-provoking exhibitions. Deitch is infamous for his belief that no distinction should exist between art and entertainment. Their personalities could not be more different.

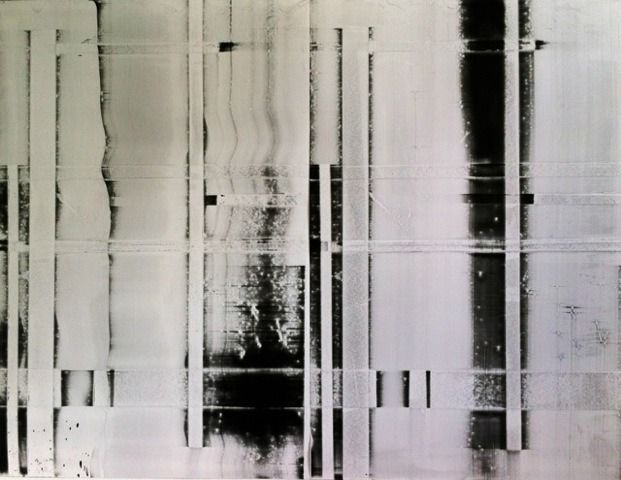

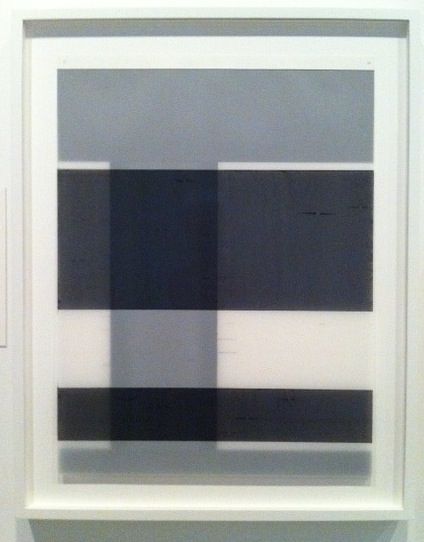

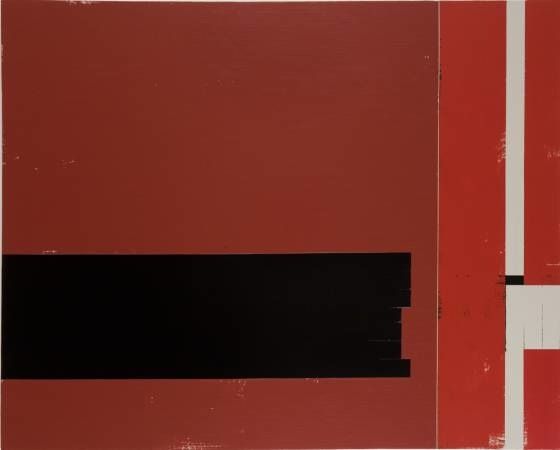

More broadly speaking, however, the firing harkens back to the fears of critics who expressed trepidation about Deitch’s appointment in 2010. Would a man who so indiscriminately embraced kitsch be a good match for the country’s best contemporary art museum? We already had questions after we saw the cancellation of their Jack Goldstein exhibition for a show of paintings by the late actor Dennis Hopper. The firing of an internationally renowned curator only further calls his leadership into question. ["Why Would MoCA Fire Chief Curator Paul Schimmel?", Art Fag City, June 28, 2012]

Jerry Saltz expresses similar opinions, fingering Broad as the man behind the scene.

Rumors of bad-blood between Schimmel and the duo of Deitch and Broad have circulated for years. That's not surprising, considering that go-go impresarios and a hard-nosed curator are like hydrogenated oil and muddy water. I've no idea whether Schimmel's shows are extravagantly expensive (as is rumored) or whether he was hard to handle (ditto). I know it's the job of a museum director to make sure curators don't run amok and overspend, though I should note that it's also a curator's job to want more. I suspect here that Deitch is probably just a pawn in Broad's game, someone to do his bidding, and that he'll eventually be gone, leaving total control in the hands of Broad and a board that he's hand-picked. (Broad is already building his own museum across the street from MoCA.)

From where I sit, the whole thing stinks. Despite solid attendance numbers, MoCA seems to be in the state the Guggenheim entered in the early 2000s, under its megalomaniacal director, Thomas Krens. MoCA is becoming a tourist attraction for one-shot visitors, a rogue institution stripped of the reputation won for it by generations of artists. Schimmel's leave-taking confirms what was already known: The institution is being damaged, enough to suggest that MoCA may no longer be a genuine member of the artistic and creative community of Los Angeles. ["Saltz on the Firing of L.A. MoCA's Chief Curator, Paul Schimmel," Jerry Saltz, Vulture, 6/28/2012]

I think he may be onto something here. Broad brought in Deitch. Broad thinks his tastes and ideas, expressed through Deitch, should rule the day. Why should a curator have so much power over what art is shown? After all, it's the Broads of the world who determine what good art is these days. They do it through the auction houses, at the art fairs, through their private museums, through their displays of their private collections at public museums, and so on.

This reminded me of an incident that has been in the news the past few weeks. This is the firing (and subsequent reinstatement) of

University of Virginia President Teresa Sullivan. Sullivan, who had been president of UVA for two years, was abruptly fired by the Board of Visitors (UVA's version of trustees). The story here is complex, but similar to the MOCA story. Powerful donors and Board of Visitors members didn't like the direction Teresa Sullivan was going with the university--specifically, they wanted a very quick transition to online university classes on the

Coursera model, which seems to be the flavor of the month. And, because they are rich and successful, they figured that whatever disagreements they had with Sullivan were a result of her inadequacies. The story of the scheme was leaked to the public and it quickly fell apart. The governor of Virginia quickly appointed a largely new Board of Visitors who reinstated Sullivan.

Some commentators have suggested that what the Board of Visitors was doing was part of a general attempt by conservative Republicans to seize control of higher education, which they see as one of the bastions of liberalism. After all, Virginia Bob McDonnel is a Republican and appointed all of the Board of Visitors. The suggestion is that if state universities are transformed into primarily trade and professional schools and away from the research institution/university model, they will no longer be liberal redoubts. And maybe this is true, but I think there is a slightly different (if overlapping) explanation, one which Siva Vaidhyanathan, writing about the Sullivan debacle for

Slate, put his finger on.

At some point in recent American history, we started assuming that if

people are rich enough, they must be experts in all things. That’s why

we trust Mark Zuckerberg to save Newark schools and Bill Gates to rid

the world of malaria. Expertise is so 20th century. ["Strategic Mumblespeak," Siva Vaidhyanathan, Slate, 6/15/2012]

And I think we are seeing this in the art world. It's a world that has always been controlled by rich people, at least on an institutional level. But there is a complex dance between professionals (curators and directors) and the big-money trustees and donors. What the MoCA firing suggests is that big money is getting impatient with this dance. And this impatience is evident everywhere these days--the museum shows highlighting specific collectors, the private museums to show off super-rich collectors' collections, etc.

But hasn't it always been so? Didn't

Nelson Rockefeller and Stephen Clark fire founding MoMA director Alfred Barr in 1943? So how is Broad, acting through Deitch and the trustees, firing Schimmel any different? I don't think it is

qualitatively different. But what we have seen is the massive rise in the number of super-wealthy individuals and a rise in this kind of meddling--whether at universities or at museums. In some cases, these wealthy individuals might be self-dealing. They get a museum to show their collection, and that causes their collection to become more valuable. But I think probably just as often there is a sense of, I'm rich, I earned my money through my wits and my savvy, therefore I am imminently qualified to be a curator or museum director--or at least pull the strings of any nominal director or curator.

In short, events like the firing of Schimmel may be just one more sign of how the balance of power in the U.S. and in the world generally has shifted away from the 99% all the more firmly into the hands of the 1%--or more realistically, the .01%. (Since the expansion of the .01% has been largely driven by economic rents extracted by the financial industry, I think we should call these people the "basis point," which is finance jargon for 1/100 of one percent.) Broad, with his fortune derived from home building and insurance, is one of the top basis points in the U.S. And he is letting us know that when it comes to running an art institution, he knows better than any seasoned professional.