There are artists and there are people who involve themselves with art. This latter group includes gallerists, curators, critics, collectors, art space and museum directors, grant administrators, art school deans and directors, etc. Let's call the latter group gatekeepers, because their work involves exercising judgment about art. The two groups overlap. And in that overlap lies the possibility of ethical mischief.

The gatekeepers bestow artistic capital on the artists by choosing them. We may struggle with these choices, disagree with them, disagree with the very notion that a choice must be made and certainly with the theoretical frameworks on which the choices are made, whether stated or implicit. But in the end, there is more art produced than can be experienced , displayed, written about, or collected. There necessarily needs to be a culling process. Gatekeepers do this.

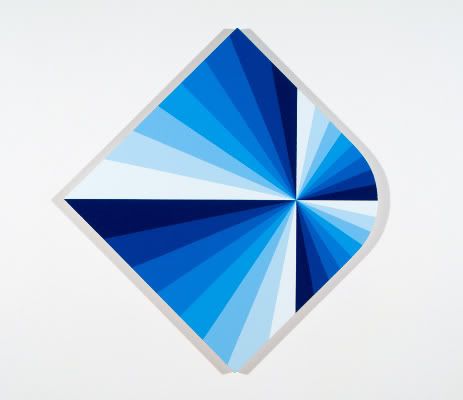

And each time a gatekeeper acts, an artist benefits. She gets some artistic capital (which, with luck, can be turned into economic capital). For example, every year Lawndale Art Center brings in a guest curator to act as the juror for The Big Show. In 2009, the juror was Laura Fried, who is an assistant curator at the St. Louis Contemporary Art Museum. Now the Big Show doesn't bestow a ton of artistic capital on the artists it shows. You haven't made it just because you had a piece in the Big Show. But it gives you a little artistic capital. You get seen by a lot of people. You get a line on your resume. And if you're lucky, you might sell a piece. That's what happened to Jed Foronda. Foronda is a young Houston artist who had two pieces in the 2009 show. I liked them and contacted him. Were they for sale? He said yes. So I bought one of them. So Foronda's artistic capital was turned into a small but nice chunk of economic capital.

But he also gained additional artistic capital by being collected. Different collectors bestow different levels of capital, of course. Charles Saatchi gives an artist he's collecting more artistic capital than, say, John and Becca Thrash, who in turn give a lot more than me. We're all collectors, but as collectors, our stock of artistic capital to spend varies wildly. But I give additional artistic capital above and beyond the meager supply I have as a collector because I'm also a critic. Foronda benefits from me not just because I bought a piece of his, but because I've written about his art. This is the way a critic bestows artistic capital. I've generally written good things about Foronda's art--but even if I had criticized it, he would have gotten a little artistic capital because being criticized by name means that your art is worth thinking about.

Jed Foronda, The Wheels Keep On Spinning (detail), masonite, magazines, 2009

But Foronda's stock of artistic capital is still pretty low. He hasn't had a solo exhibit (as far as I know), which would be how a curator would shell out artistic capital, nor is he represented by a commercial gallery (as far as I know), which is the main way a gallerist pays out artistic capital.

The reason I'm talking about this is because the ability to bestow artistic capital is power. And power can be abused.

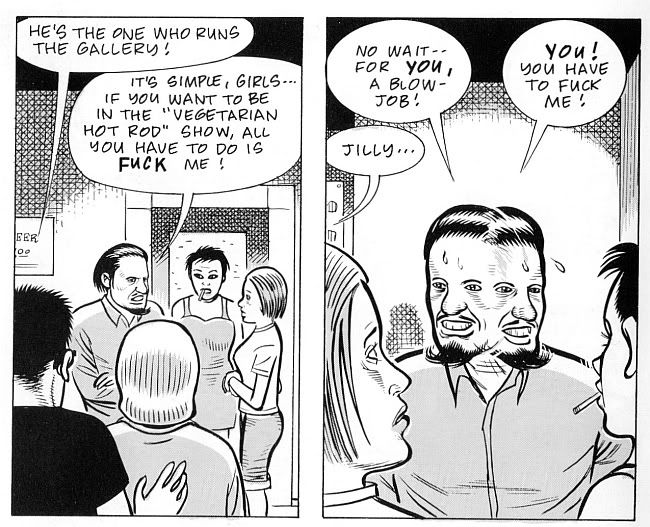

Dan Clowes, from "The Artist's Life" (collected in Pussey!)1993

This abuse can be overt and obviously malign, as in these panels from one of Dan Clowes's scabrous "Dan Pussey" stories. But a different ethical issue for gatekeepers came up in conversation this weekend. What if you are a gatekeeper? You have an artistic soul, and maybe you studied art. Maybe you're a Sunday painter. Do you exhibit your own art? Do you promote yourself as an artist, in addition to being a (gallerist, critic, curator, collector, etc.)?

My answer is that you probably shouldn't because you already have some power, some artistic capital to spend. If someone else wants to be on the receiving end of your artistic capital, they won't want to turn you down when you ask to be in a group exhibit or gallery show, or if you ask to have your stuff reviewed. So because of the power you have, you may displace an artist who has no power. You, as a gatekeeper with artistic capital to spare, might prevent an artist with none from being in an exhibit or a group show, all because of your own artistic vanity.

The thing is, there are curators and artists and gallery managers and owners and even collectors who do their own artwork. They are sincere and serious artists. But for me, from an ethical point of view, they need to be very careful about what they do with their art. They need to make sure that they are not getting shown because of their position in the art world, because of the artistic capital they have in their pockets to spend. In general, I think they should err on the side of not being exhibited. But that might be my inner goody-two-shoes talking.