The middle gallery exhibit is kind of a weird hodge-podge. It's just called "Group Exhibition," and it features work by David Ireland, Jess, James Drake, and Jay DeFeo. Why these artists?

James Drake, Snakeskin Engine, motorcycle engine, python skin, 1994

That question applied to James Drake is easy to answer. He's one of the artists that Moody Gallery represents. And right now, he has a large show on view at the Station Museum. And as Don Thompson contends in the $12 Million Dollar Stuffed Shark, being shown in a museum adds brand value to an artist. So while Drake's brand is being enhanced, why not remind people where you can buy Drake (for you have $30K to spare)?

James Drake, Spoiled, graphite, tape on hand-cut paper, 2010

But what about us plebes who don't have $30K? Well, if you're like me, and you liked the Drake show at the Station Museum, this gives you a chance to see of couple of more excellent pieces by the artist. And that's an important service that commercial art galleries perform--they are like little free museums. I don't have much to say about Snakeskin Engine that I didn't say about a similar piece at the Station Museum, but check out Spoiled! This cut-paper technique was one Drake used in a few pieces at the Station show. I didn't get a good photograph of them then, but I liked them. They seem very delicate and almost feminine, which something unexpected from an artist as consistently macho as Drake. But Drake undercuts this femininity. One of the Station Museum cut-paper pieces shows a snarling dog. This one is, obviously, spoiled--dirtied and torn. Drake's work is filled with pain and regret at male violence. Perhaps here is is addressing specifically violence by men towards women. At least, that seems like one possible reading. (This ambiguous machismo is, to me, the hallmark of certain artists associated with Texas--Drake, James Surls, and Michael Tracy.)

Jess, Xrysxrossanthemums, collage, 1978

But as I mentioned, there are also pieces by Jess and Jay DeFeo, two artists associated with the San Francisco beatnik scene. Why pull these out of storage (besides their excellence)? In the case of DeFeo, she has work up right now in the Menil as part of their recent acquisitions show. A little branding there, maybe. And Jess? I don't know. While he does have work in the excellent Poems & Pictures show at the Museum of Printing History, but it's hard to imagine that adding much brand value to Jess's work. But maybe just because that show will remind a few people about Jess, Moody thought it worth the effort to bring this piece out of storage. But another reason is that it might remind people of classic Al Souza.

Al Souza is probably best known for creating dense collages out of picture puzzles. While there are lots of collages here, none of them are made from puzzles, and generally they feel less visually choatic than the puzzle collages. He uses circular forms in several of them, including Man Holes.

Al Souza, Man Holes, cut paper, 2009

This collage is arranged in six concentric circles. The circles alternate between black and white images of manhole covers and color images of orchids, with a single manhole cover at the center. I loved this utterly unexplicit but nonetheless rather smutty picture. Of course, one is supposed to think of vaginas when one looks at the orchids. Now to consider a vagina to be a "man hole" is pretty damn crass, but what can I say--it's right there on paper. (I wonder, though, if I would have made the association without the title.)

Man Holes is both beautiful and juvenile, which seems to be a tension that Souza likes to play with.

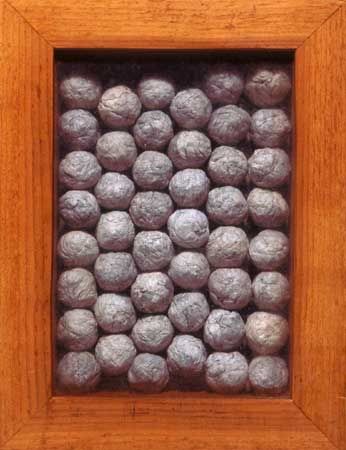

Al Souza, 46 Big Spitballs, paper in wood and glass box, 2005

This is an older piece and has even been displayed at Moody Gallery before. But even with a relative bargain price (at $3000, it's the cheapest piece in the show), it may be a hard sell. I'm guessing spitballs are a little too cutting edge for the Houston collecting community. I like it--I think it looks great and I am happy to be slightly creeped out by it.

But don't get me wrong. I picked out two works which have a kind of 11-year-old boy taboo quality to them, but the whole show is not like that. There is a lot of humor in the works, but also elegance and beauty.