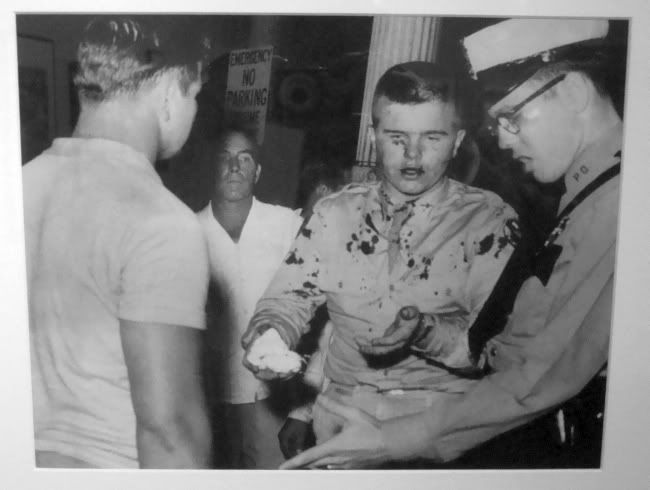

Marvin Zindler, unidentified photo from The Houston Press, 1950s

Most photography shows never get the publicity that Bayou City Noir has gotten. Younger Houstonians or folks who have moved here in the past few years may find this a bit perplexing. But for the rest of us, Marvin Zindler is an icon. He is best known for being the flamboyant consumer affairs reporter for KTRK. Many may also know him as the crusading reporter who got the Chicken Ranch, a rural brothel in LaGrange, closed down. These hardboiled crime photos are a bit of a revelation, but they fit in perfectly with his muckraking career.

What hasn't been discussed as much as Zindler himself is the paper that published them, The Houston Press. In the 1950s, Houston had three major dailies--the Houston Chronicle, the Houston Post, and the Houston Press. The Press was a Scripps-Howard newspaper that was bought out by the Chronicle in 1964. Of the three Houston papers, it was the most tabloidish.

For the nostalgists among us, the key figure at the Press was Sig Byrd, a brilliant columnist who walked among the low-lifes and common folk of Houston, getting their stories for his column, "The Stroller" (a perfect name for his column because Byrd was truly a flâneur). This, to me, is the magic of tabloid newspapers--that they will cover areas of local life that are invisible to more gentile outlets. Sig Byrd is pretty much forgotten today--his book collection of columns, Sig Byrd's Houston, is long out of print. There is a Facebook page devoted to it (which I founded), and Robert Kimberly, a relatively recent immigrant to Houston, has been doggedly scanning old Stroller columns from the U.H. microfilm library and posting them on Flickr.

Sig Byrd would go out among the poor, the African-Americans, the Mexican-Americans, the waterfront types, the barflies, the streetcorner preachers, the prostitutes--people ignored elsewhere in society except to be condemned. He would listen to their stories. He probably embellished them a bit. The result was some of the finest writing ever done in Houston.

Zindler's photos aren't quite as good and Byrd's columns. They also feel like weak echoes of Weegee. Like Weegee, Zindler staged a lot of his photos. I get the impression that this is a journalistic no-no, but those journalistic ethics of impartiality are rules for the bourgeoisie--for people who go to college to study journalism. If Zindler got to the scene a few minutes late, why not pose the participants of the real-life drama that he had just missed. It tells the story better. Not only would he stage some of his photos, he also extensively retouched the photos so they would reproduce better in the paper.

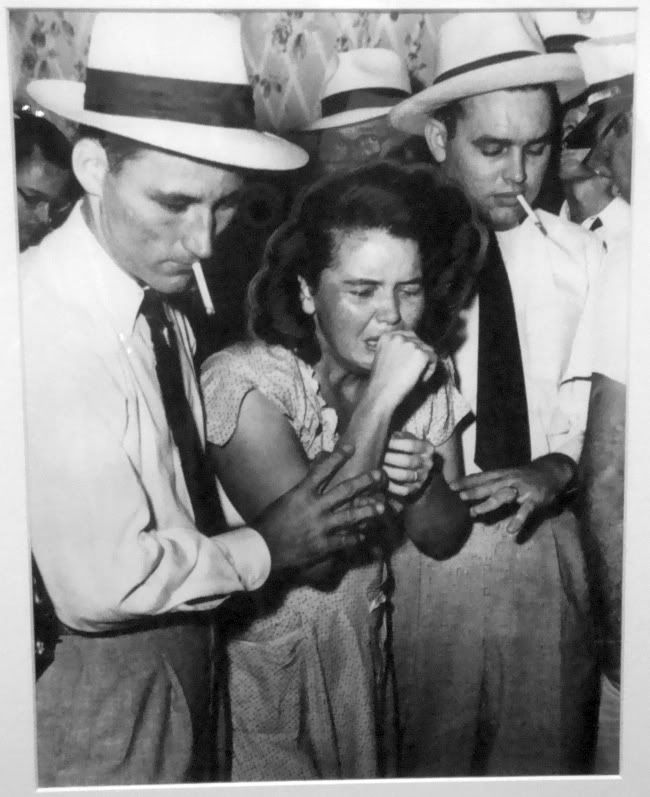

Marvin Zindler, "Husband Was 'Acting Cute'--Now He's Dead," Houston Press, May 22, 1953

If you look closely, all the highlights in the woman's hair are painted in. This helps her head to pop from the background and gives her hair a feeling of three-dimensionality. So is this cheating? Did Zindler deviate from the truth of what the camera saw when he retouched photos? Did he deviate from journalistic truth when he posed photos?

Zindler didn't shy from showing blood and guts--far from it. Tabloids knew their readership wanted to see blood.

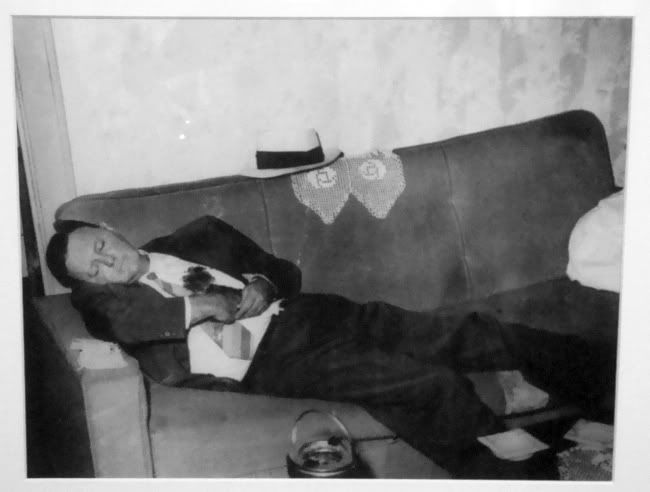

Marvin Zindler, date and headline unknown

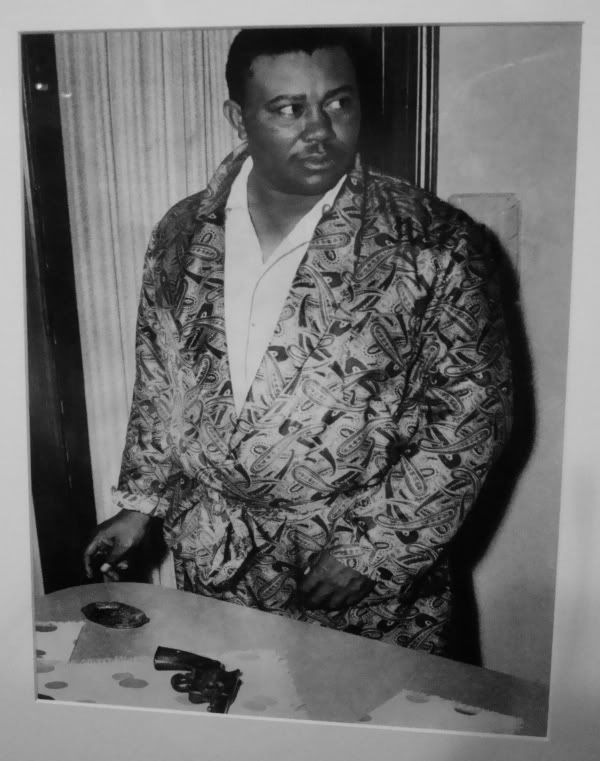

One weird thing about the exhibit is that all the criminals, victims, lawmen and bystanders are white, except in one dramatic photo.

Marvin Zindler, "Bomb Home in Riverside!" Houston Press, April 17, 1953

Jack Caesar, a cattle trader, had moved into Riverside Terrace, then a white neighborhood. Someone then bombed his house. So the only time Zindler photographs a black man is when he is a victim of racist terrorism. The scared but defiant Caesar is a good subject. But contrast this to Byrd, who regularly wrote about African Americans and gave them a degree of humanity that wasn't all that present in the media of the time, particularly in a Southern city like Houston.

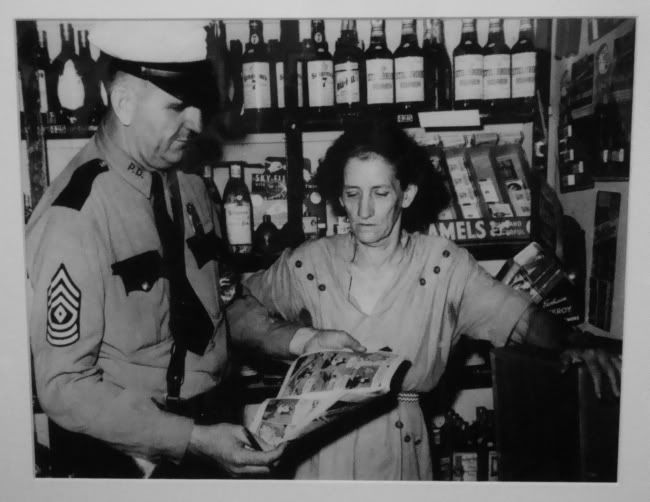

Marvin Zindler, date and headline unknown

Some of the best photos are some of the most inexplicable. Why are this woman and this cop reading a Felix the Cat comic book in a liquor store? I'm sure the explanation is banal, which makes it all the better that there is no explanation in the exhibit.

These photos are fascinating and maybe occasionally they rise to the level of art. But I wonder what people thought of them and of the Press in the 1950s. Was it a disreputable tabloid, the kind of paper respectable folks didn't take? I think of the terrible local TV news with their "if it bleeds, it leads" mentality. Sixty years from now, will curators be showing videos from them in museums? Time can certainly change our perceptions--these photos pandered to the bloodlust of the Press's readership, like gladiatorial competitions did for the Roman masses. Yet sixty years later, we can look at a long-dead bloody corpse and discuss it as art.

Tweet

Great story. Thanks for sharing. I also liked the photos. And yes I do remember Marvin Zindler.

ReplyDelete