As you might expect, however, this hasn't been constant. From January to August, I got about 2570 page views a month. Then I discovered Reddit. I started posting my posts in appropriate Reddit forums, and my page views show up. After September, my average page views per month were about 6360 per month. Now this may be as good as it gets. After, my two main subjects, contemporary art in Houston and art comics, are not hugely popular. There's a reason Gawker covers celebrity gossip instead of contemporary art.

Reddit surprised me in another way--the posts people liked the most weren't necessarily what I would have guessed (although in retrospect, their popularity makes sense). Here are the ten most popular posts from 2010, based on page views.

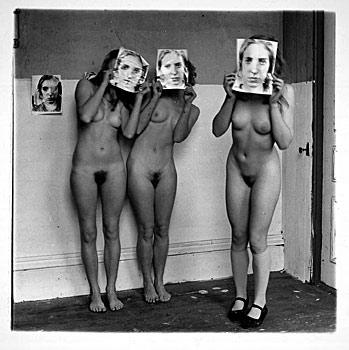

Francesca Woodman, untitled, photograph, 1976

Francesca Woodman, untitled, photograph, 1976

1.The Woodmans: This post was about a film about the late photographer Francesca Woodman and her family. When I posted it up on Reddit, the number of people visiting Pan exploded.

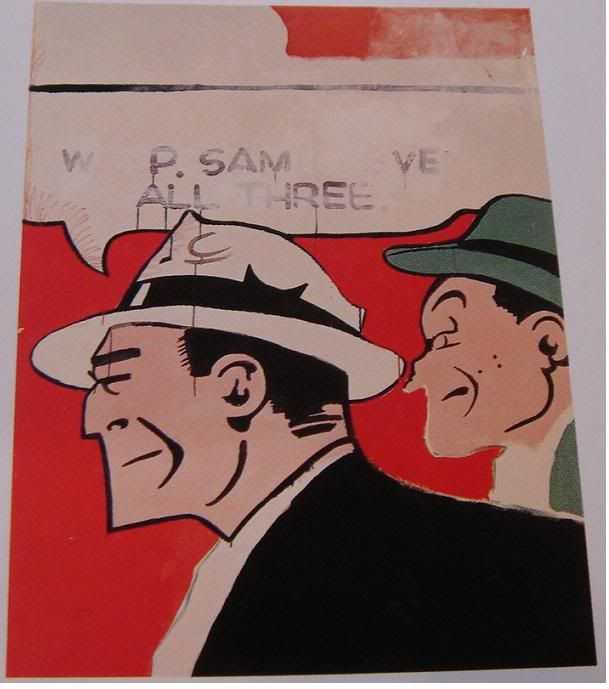

Andy Warhol, Dick Tracy, 1960

2. Where Does a Work of Art Get Its Value? This post was from September 2009, but when I posted a link to Reddit, it took off. That said, it is a post that readers often manage to find--the issues surrounding what makes a given piece of artwork valuable are always interesting.

Tara Donovan, Bluff detail, buttons and glue, 2007

3. Lady Art at McClain. This is another one from last year (December 24, 2009). It's about an ill-conceived group show at the McClain Gallery, which is about the bluest of blue-chip galleries in Houston. Why is it popular? I don't know--I can't credit Reddit for this one. I will say one thing about it, though. I was really snarky--it's one of the few bad reviews I've written. And given the way people liked it, maybe I should write some more!

Norman Lindsay, Visitors from the Moon, watercolor

4. Two Books by Norman Lindsay. This post was a review of a novel and a memoir by the eccentric Australian erotic artist, Norman Lindsay, with whom I became somewhat fascinated by over the course of 2010. Why is this post so popular? Well, I suppose it's that sex sells!

5. Every Painting in the Museum of Modern Art. I wish I could say that it is my writerly brilliance that brings readers to Pan, but this popular post demonstrates otherwise. It is essentially a repost of a video from New York Magazine.

Michael Crowder, Du musée Sauvignons detail, glass, 2009

6. L'heure bleue d'Michael Crowder. This is another post from 2009 that somehow has remained popular throughout 2010. The gallery linked back to the review, which I presume drove some of the views. But really, I don't understand why this post--a review of a nice show by a Houston-area artist--should have been so much more popular than many other similar posts.

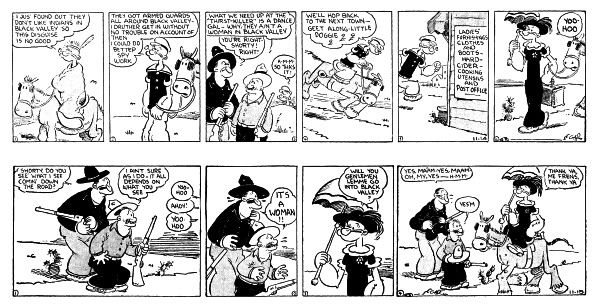

E.C. Segar, Popeye daily strips

7. "I Yam What I Yam" On the other hand, I know exactly why this post is so popular. It's a post about how frequently E.C. Segar, the creator of Popeye, put Popeye in drag--and how comfortable Popeye seemed to be cross-dressing. It was a response to a post by Jeet Heer on his excellent blog Sans Everything. He mentioned my post on his blog, which sent some readers over. Apparently, someone at the popular liberal blog Alas! A Blog saw Heer's post and posted a link. Which was very nice. That said, I don't think that posting about cross-dressing comic strip characters would, in general, increase my readership. (This post appeared exactly one year ago today.)

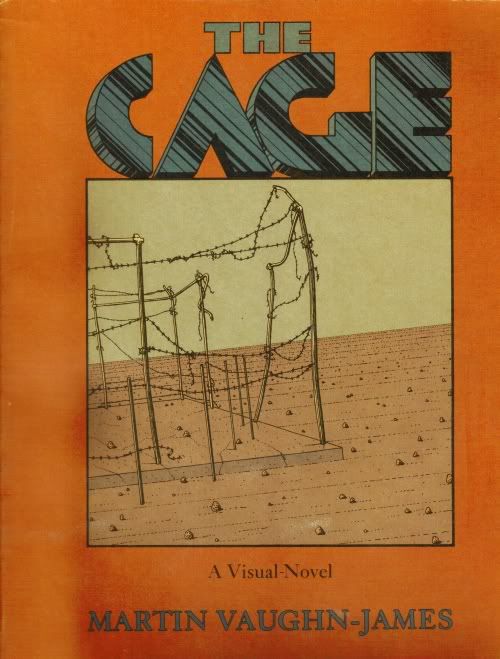

Martin Vaughn-James, The Cage cover, 1974

8. The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James. This one was from November, 2009. It, like many others, was given a new lease on life when I uploaded a link to Reddit. On the face of it, it seems strange that an avant garde graphic novel published in a small print run in 1975 should be of any interest to readers today. But it has a kind of mystique attached to it, and many contemporary readers and creators of art comics are extremely curious about it. It's an amazing work, and one that should be reprinted.

Laurel Nakadate, Stay The Same Never Change film still

9. What I Saw When I Saw Stay the Same Never Change. I saw this Laurel Nakadate film during FotoFest. I hated it. I wrote a highly negative review and quoted some hilarious things Nakadate said about the film. Perhaps this is a signal that I should continue to write negative reviews. Or perhaps it just means that Nakadate remains a popular search engine subject (maybe for artsy people who like to see naked ladies--which would help explain the popularity of the Francesca Woodman post as well).

still from Boogie Woogie

10. I Saw Boogie Woogie So You Don't Have To. This post is sort of a review of this movie set in the art world. And it is pretty negative, which strongly suggests a trend. BUT! It also has nudity--boobs to be precise--so that's another trend. That's what you people like--snarky negative reviews with naked boobs.

So that's it--the most viewed pages of the past year. Expect to see more crossdressing cartoon characters, more boobs, more bad reviews, more movie reviews, and more reposting of popular posts from other blogs. Happy New Year!