This will be a bit similar to my "best comics" list in that it reflects my favorites among those books I read that were published in 2015. And reading art books is a bit different from reading comics and graphic novels. Almost all the comics I read are very recently published--usually within the same year I read them. This is absolutely not the case with art books. I might become interested in an artist (for example, both David Hockney and Patrick Caulfield this year) and in researching them, I read old biographical works or catalogs. If it's an older book I read, I left it out of this list. Only 2015 books are listed here here, even though they constitute less than half of the art books I read in 2015. And, of course, this list reflects my own passions; that implies that there are undoubtedly many great art books published this year that are not listed here just because I wasn't interested enough in the subject to read them. With those caveats, here's my list.

Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry edited by Paul Gorman with essays by David Hockney, John A. Walker, Chris Stephens, Lisa Tucker, Guy Brett, Paul Gorman, David E. Brauer and Jim Edwards, and Christopher Finch (Thames & Hudson).

edited by Paul Gorman with essays by David Hockney, John A. Walker, Chris Stephens, Lisa Tucker, Guy Brett, Paul Gorman, David E. Brauer and Jim Edwards, and Christopher Finch (Thames & Hudson).

This year I have followed an interest in British Pop art (as mentioned above), so it is only natural that I'd want to read this book. Additionally, Boshier has an important connection to Houston: he taught at the University of Houston from 1980 to 1992 (with a return term in 1995). Many artists I know remember him as a beloved teacher. As a fan of comics, I always think of him as a teacher of two of my favorite cartoonists, Eddie Campbell and Scott Gilbert. His career has been unusually rich and diverse. He was indeed a pioneering Pop artist, part of the second wave of English Pop artists (the first wave occurred in the mid-50s; Boshier and his classmates, including David Hockney, were students at the Royal College of Art in the late 50s/early 60s). In 1962, Ken Russell filmed a very amusing documentary about Boshier, Pauline Boty, Peter Blake and Peter Phillips, which you can watch in its entirety on YouTube.Boshier's early work definitely reminds me of Hockney's early work--they shared a studio and both had quite painterly styles. Eventually Boshier's work evolved in a more hard-edge direction. And as the 60s progressed, he gave up painting in favor of other media--photography, collage, film, etc. It was a path a lot of artists were taking, but what Boshier couldn't do was be a minimalist or post-minimalist. He comes close at times, but his work remained too much a part of the world. He was interested in culture and politics and couldn't turn away from that completely.

He was also teaching art in the 60s and 70s. One of his students was John Mellor, who later changed his name to Joe Strummer. This relationship lead Strummer's band, The Clash, to hire Boshier to do two books of illustrated Clash lyrics (generously reproduced in the book). In addition, he did the cover of Lodger, the great album from David Bowie's Berlin period.

By the time he moved to Houston, he had started painting again, and his painterly approach seemed to place him right in the then current Neo-Expressionist movement. His paintings from that period are scabrous and often satirical, but it's his handling of color and mood that make the biggest impression on me. A painting of male and female KKK lovers is not just funny and outrageous, it's beautiful as well. When I look at these works, I am reminded a bit of Earl Staley's 70s and 80s painting, and I wonder if there was any mutual influence.

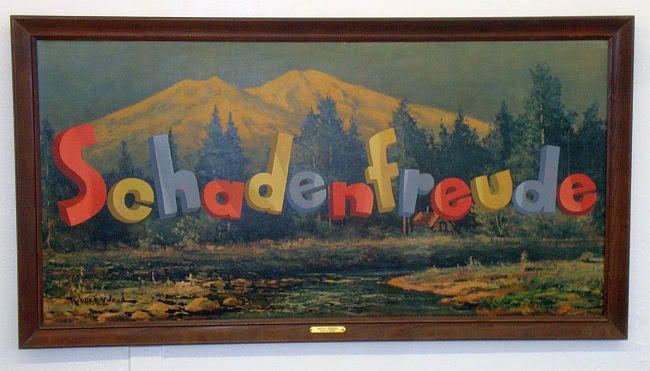

The work he's done since then while living in Los Angeles has in a way combined all the previous tendencies--multi-media, painterly, Pop, collage, satire, etc. The only new thing is that much of the work reflects his love of the city he adopted, Los Angeles.

The book is beautifully designed and the essays are pretty good. And it is very generous in terms of the quantity of art reproduced. I know Boshier has had retrospectives before, but this volume suggests another one is due.

Welcome to Marwencol by Mark E. Hogancamp and Chris Shellen (Princeton Architectural Press).

by Mark E. Hogancamp and Chris Shellen (Princeton Architectural Press).

I've written about this book already, so suffice it to say that it combines a compelling biography of Hogancamp with Hogancamp's amazing photographs. In an ideal world, the biography of the artist wouldn't matter, but it does to me as a reader. I like good stories, and Mark Hogancamp's is harrowing and inspiring.

Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century by Jed Rasula (Basic Books).

by Jed Rasula (Basic Books).

You take a few art history classes and you think you have the basic story of Dada, but you don't. Part of the reason is that what art historians learn and teach about Dada is all about the visual art. Maybe a little about the performances and some of the provocations that feel like modern performance art. But Dada was a literary form, too, and many of the greatest Dadaists were poets. Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, the co-founders of Caberet Voltaire, Tristan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck and many others who have well-known associations with Dada, but never produced any of the visual art associated with the movement. To Ball and Hennings, Dada was primarily about performance. They were Germans who fled Germany shortly after the outbreak if WWI because of their antiwar activities. Hennings was forging passports for war-resistors and had been caught. Using false passports she had made, she and Hennings slipped into Switzerland, where they worked in low-level vaudeville shows. This gave them the idea for an artists' cabaret, which became Cabaret Voltaire. It was surprisingly popular.We Americans are proud of our part in Dada, when Duchamp and Picabia showed up in New York and met Man Ray. But outside of Switzerland, the center of Dada was in Germany. This history felt a little more conventional than one might expect--artists who liked or disliked one another, trying to decide who was really a Dadaist or not, etc. The story of the affair (which was both artistic and erotic) between Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch turns out to be an important part of the story. There are figures like Johannes Baader, aka "Oberdada", who I had never heard of until I read this book--he was a self-aggrandizing figure who managed to alienate the other Berlin Dadaists.

The thing is that Dada really only survived a few years. By 1921, it was mostly over, even though the people we associate with Dada--George Grosz, John Heartfield, Jean Arp, Ray, Duchamp, etc.--were really still at the beginning of their creative lives. Destruction Was My Beatrice does describe how Dada's ripples landed on other shores around the world, but focuses primarily on what was happening in Switzerland, France, the USA and Germany above all. Rasula makes a point of writing about female Dadaists like Hennings, Höch and Mina Loy and the sexism they faced even within the Dada community.

Art Chantry Speaks: A Heretic's History of 20th Century Graphic Design by Art Chantry (Feral House).

by Art Chantry (Feral House).

Art Chantry is a designer perhaps best known for his design for The Rocket, a music newspaper published in Seattle form 1978 until 2000. Because he was there during the rise of grunge, you can also see a lot of his design work on album covers of the era. He was a resolutely low-tech designer. When his peers had adopted the computer, he continued to use X-Acto knives and rubber cement. For example, in designing the column headers for The Rocket, he used one of those old plastic label-makers. The effect felt really "punk" without imitating any of punk's classic design (like Jamie Reid's immortal "ransom letter" type for the Sex Pistols).For several years, he wrote blog posts on Facebook about the weird, sometimes vernacular and anonymous design that inspired him. This book collects those posts, He was quite influenced by what he called 20th-Century American industrial graphic design, which seemed in a way Modernist, but was effected by guys who had "never heard of Milton Glaser or Paul Rand or Helvetica" and learned their trade "by either working in a print or sign-painting shop, in the Army, or taking mail order classes advertised in the back of Popular Mechanics." One of Chantry's best known posters was a direct homage to this kind of design.

Art Chantry, poster for the Night Gallery, COCA Cabana, the Center on Contemporary Art in Seattle, Washington, 1991.

The book looks at design trends and individual designers from the past that have largely been written out of the history of graphic design. One thing Chantry does is show us design ideas that were ubiquitous once but now forgotten. But at the same time, he also digs up obscurities that were never very well-known or influential in the first place. He's the kind of guy who spends his time combing old magazine shops (these used to be not uncommon businesses, believe it or not), junk shops, etc., for something that catches his eye. Then he researches it. This book is the result of those obsessions.

The book is the size of a standard prose trade paperback, but is generously illustrated in color. It won't surprise most people to say that it looks great. Personally, I think it's difficult to be an original graphic designer these days. In fact, the last time I was really excited by print design was when I was living in Seattle and Chantry was un-writing the rules. This book reminds why that was so exciting.

The Collected Hairy Who Publications 1966-1969 by Dan Nadel (Matthew Marks Gallery).

by Dan Nadel (Matthew Marks Gallery).

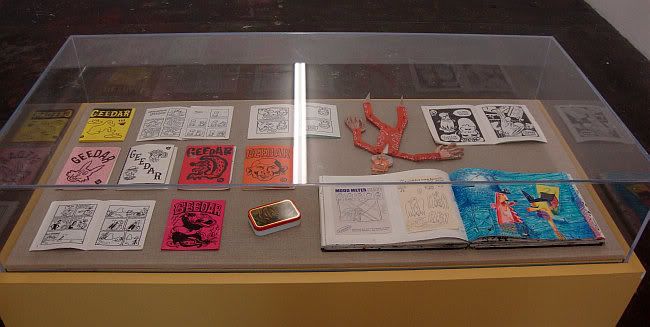

Dan Nadel curated a show called What Nerve! which I saw at the RISD Museum. It traveled to one other location. It was a weird place for a museum show--Matthew Marks Gallery. But we've started seeing this a lot more lately--large New York art galleries acting like museums. The relationship Nadel established with the gallery was clearly a productive one, as they published this deluxe reprinting of all the Hairy Who's comic books/show catalogs.In 1966, when they had their first group exhibit, the Hairy Who (Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, Karl Wirsum, Suellen Rocca, Art Green and Jim Falconer) decided to publish a comic book instead of the traditional show catalog. This went over so well that they did it for all their shows (four in all). These four comics comprise about 2/3rds of this book. Nadel has taken a lot of care to reproduce them legibly while retaining their status as objects. (This is not typically how comics are reprinted, even in the most deluxe editions. They usually foreground the artwork independently from its previous existence as an object--a comic book).

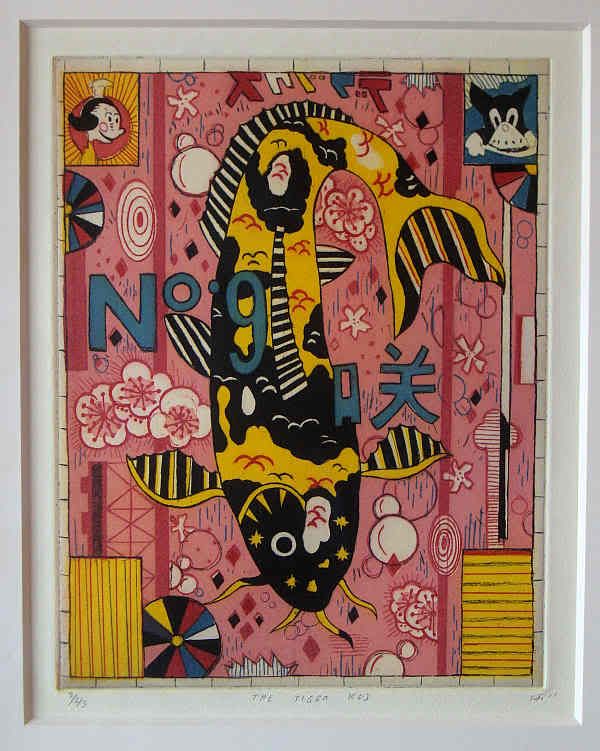

Karl Wirsum, Serration Saturation from the The Hairy Who Sideshow, 1967

The book ends with a section of posters, artists photos, drawings, chairs (!), installation photos and other ephemera. I like this because it gives one an idea of what it looked like to be a member of the Hairy Who. And while I like looking at the artwork very much, I also want a catalog like this to provide contextual/biographical information, whether written or photographic.

I have to say I have coveted these comics ever since I read about them as an undergraduate in the mid-80s. They were listed in The Official Underground and Newave Comix Price Guide by Jay Kennedy (a bible for me at the time, not because I cared about the prices, but just as an encyclopedic handbook), but I never actually saw one in the flesh until decades later. Now here they are, published in a beautiful hardcover. The wait was worth it.

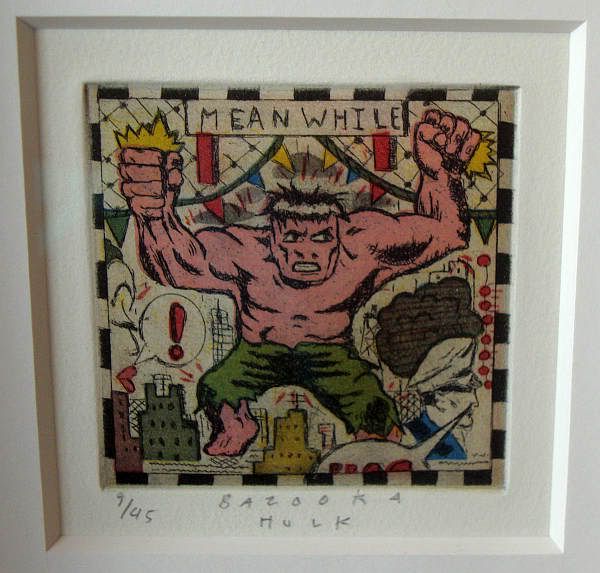

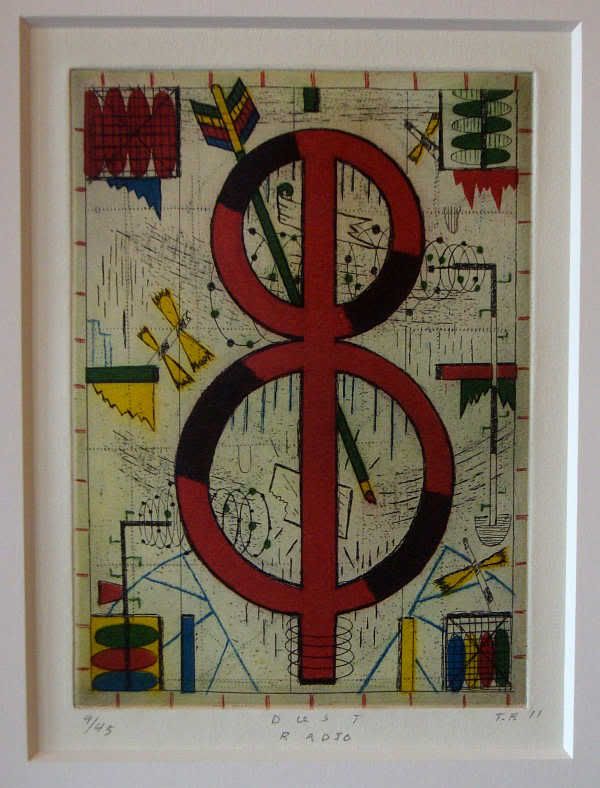

Dime Stories by Tony Fitzpatrick (Curbside Splendor).

by Tony Fitzpatrick (Curbside Splendor).

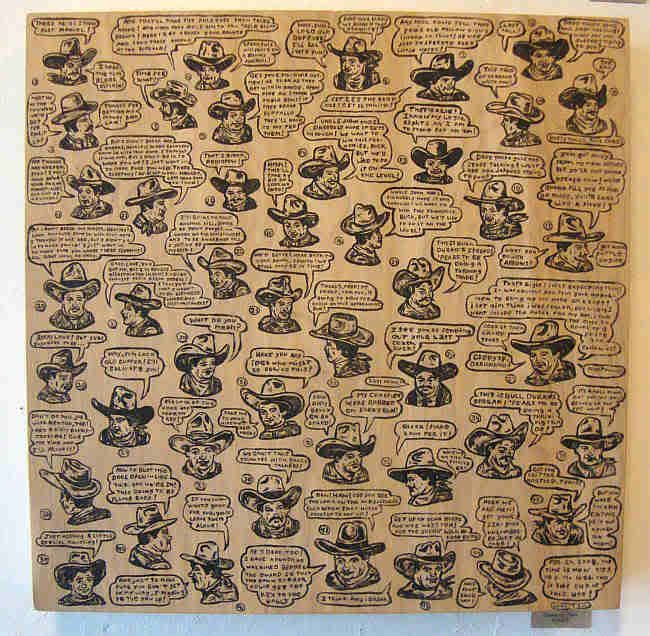

I saw a lot of this work on Tony Fitzpatrick's blog. A blog post would contain an image, consisting of drawn elements and collaged elements, and a prose section. The images would incorporate poems written by Fitzpatrick. It's very dirty art--written, drawn, pasted, prose and poetry all mixed up.Fitzpatrick comes across as a kind of professional Chicagoan sometimes--the city and its mythology is one of his favorite subjects. The essays (or feuilletons) touch on whatever is capturing Fitzpatrick's attention at a given time--places he's been recently (New Orleans, Ohio), characters from his life, past and present, politics (local and national), art and culture. His writing is at its best when he's telling a story.

The relationship between each essay and the accompanying piece of visual art may only be tangential, but they work together. And if he seeks to embody a certain urban, Chicago sensibility in his writing (with middling success), his images always feel like Chicago in my eyes--busy and dense like a crowded neighborhood. The collaged elements show Fitzpatrick as a nostalgist (many of them are matchbook covers for long defunct businesses), and his drawing reminds me a bit of the great Chicago "outsider" artist Joseph Yoakum. His flea-market/"outsider" aesthetic shows his connection to the Chicago Imagists (such as the Hairy Who), but he is about 20 years younger than they are. It suggests that maybe there is a thing in Chicago that produces artists with these sensibilities (earlier artists like Leon Golub and H.C. Westerman had it as well as contemporaries of Fitzpatrick like Kerry James Marshall).

I love Fitzpatrick's art and enjoy reading his essays, and this handsomely produced volume displays both very well indeed.

Philip Guston: Prints: Catalogue Raisonné (Sieveking Verlag).

(Sieveking Verlag).

I was a little surprised by how few prints Guston did in the course of his career. He started relatively late--the earliest print listed is from 1963. The first 19 prints (mostly lithographs but also one silkscreen on plexiglass (!)) are abstract. They were all done between 1963 and 1966. What struck me is that figuration was trying to break on through. Perhaps this is a side effect of the graphic, drawn nature of the work. But almost all of these prints show a field of distinct visual objects or figures. They're still abstract, but it seems clear that Guston just needed a little push.There is a gap until 1970 for his next lithograph, and suddenly we are seeing the figuration that we came to expect from Guston. But the medium itself is not an important one for Guston. After the first figurative lithograph from 1970, he doesn't do another print (except for a poster design) until 1980.

Guston died on June 7, 1980, and that half year was a semi-annus mirabilis for graphic work. He published the majority of the prints he would ever do in those short five months. Twenty-five beautiful editions were published in 1980 (all printed by Gemini G.E.L.). Additionally, he had 12 unpublished proofs in his studio when he died, which are included here. Most of these unpublished proofs look finished to my eyes, but there are a few which I can imagine that had Guston lived, he might have worked on a bit more.

These 1980 prints are bold and grungy. This book is a beautiful document of an aspect of Guston's art that was only reaching its peak the year he died.

Out of Sight: The Los Angeles Art Scene of the Sixties by William Hackman (Other Books).

by William Hackman (Other Books).

By this point, a LOT has been written about the 1960s art scene in Los Angeles. The standard story is that a bunch of young artists in the late 50s were discovered by Walter Hopps, Ed Kienholz and Irving Blum and shown at Ferus Gallery. A lively scene happened for a few years but then fell apart by the end of the 60s and L.A. art went into a period of decline. This story is only partly true--L.A. art never really declined, just the commercial gallery scene. Plus, there was a lot of stuff happening that had nothing to do with Ferus.My favorite book on this subject is Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s

The thing is that the art scene as a site for mostly white men really did die in the late 60s. Galleries closed or moved and the artists themselves scattered hither and yon. The scene grew much more diverse and disconnected in the 70s. There's a good book about that, too--Creating the Future: Art and Los Angeles in the 1970s

Drawing Blood by Molly Crabapple (Harper).

by Molly Crabapple (Harper).

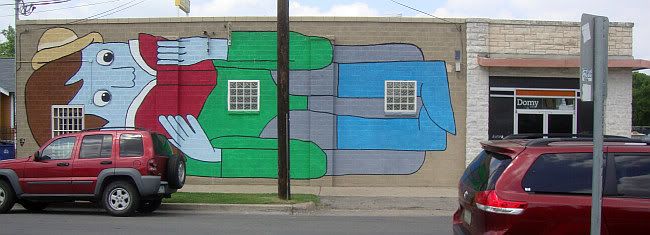

Molly Crabapple is an artist best known for her pen & ink & watercolor journalistic illustrations. She is one of the few contemporary artists who specializes in drawing as journalism, in fact. (Joe Sacco, who provided a blurb this book, is one of the others.) This kind of art is mostly ignored by the contemporary art scene, which shows how narrow the contemporary art scene can be sometimes. This book is a memoir of the 33-year-old artist. It may seem like a young age for a memoir, but she has had an unusually action-packed life. One thinks of artists often as inherently un-bourgeois, but most artists I know live utterly conventional lives compared to Crabapple. The daughter of a professional artist and a political activist, she was roughing it in Europe as a teenager, sleeping on the spare beds at Shakespeare and Company and sleeping with older men who acted as her mentors. She used her beauty that way, and writes about her affairs thrillingly. She also posed nude regularly at the Society of Illustrators in New York, which allowed her to make contact with many of the best illustrators in town. She got involved with the revived burlesque scene in New York and was one of the first Suicide Girls. But she quit them when their contracts and business practices became oppressive.All along, she was drawing, ultimately studying at the Fashion Institute of Technology (which she hated and derides repeatedly; she eventually dropped out). As an artist and a "professional naked girl" (as she puts it), she became deeply involved with the culture of alternative sex work, becoming at one point an artist-in-residence at Box, a high-end sexy cabaret in New York that charged its Wall Street bro clientele top dollar for bottle service to see some truly wild burlesque and live sex entertainment. But while painting a mural for a new Box opening in London, she became aware of the anti-austerity protests happening at British Universities and started to wonder whether her work titillating the ruling class was what she really wanted to do with her life. (This was in 2010.)

That winter in London politicized her and her art. She was very much involved with Occupy and has done journalistic writing and illustration from Guantanamo and Greece and Syria and elsewhere.

Crabapple has a fast-moving writing style. Her art is full of little flourishes and filigree, but her writing has a journalistic directness. She has a talent for an inspiring aphorism or quote. Here are a few:

"Why should I feel bad for using my looks? Or the fact that I'm a woman?" Cosette asked. "Think of all the things I haven't gotten because I'm a woman."There are a lot more like this. She has some zingers for the art school establishment and especially for MFAs (and most especially for MFAs from Yale), whom she refers to as trust-fund artists. She is obviously someone with little interest in art theory, conceptualism, high-end white cube galleries, and much of what we think of as being "the art world." She sees the difference between the art world and what she does as a class issue. She referred to artists like herself as possessing a "blue-collar level of craft." And Drawing Blood is written in a prose style that is the exact opposite of international art English.

...

When I was seventeen and drawing at Shakespeare and Company, art felt closer than my skin. I'd cared about things beyond professional advancement. I used to think my pen could fight me into a new world.

But for the past few years, I'd let that part of me die. What had started as a scramble to scrape together enough resources so I could afford to draw had become an obsession with the resources themselves. I was twenty seven [...] I had spent years--wasted years?--doing work for cash instead of desire.

...

In the winter of 2010, the world started to burn.

I was painting pigs in Nero's nightclub.

As I read Drawing Blood, I imagined that bohemian 20-something-year old girls might find her an aspirational role-model and bohemian 20-something-year old boys might fall in love. But I was a little put off by the way older men were into her--the kind of guys who think of themselves as progressive and "cool", like comics writers Neil Gaimen and Warren Ellis (both of whom have walk-on roles in Drawing Blood). Here was this super-talented, interesting, politically progressive artist who also happened to be a sexy (often naked) goth girl. Crabapple allows them to be dirty old men without guilt. But I think her view was the same as the one she assigns to her friend Cosette above. She uses this interest by older men to her advantage repeatedly and without apologies.

The book is heavily illustrated. I think many of the illustrations were original for this book, but others are examples of the work she was doing during whatever episode in her life she is writing about. The art is mostly reproduced in color and is well-integrated with the text.

I have mixed feelings about her art and writing, but I love the fact that she is writing and drawing with evident passion. So much art these days seems bloodless and designed to slot easily into some artistic or intellectual tendency. That kind of art pushes me away. And despite my somewhat mixed feelings toward it, Crabapple's art and writing have the opposite effect on me.

I realize that this "best of" list makes it appear that I am not interested in sculpture, nor in performance art, conceptual art, photography, social practice, installation, video, etc. Not so! But I confess that this year has been a year in which I looked back at art that barely registers on the art world, that is mostly untheorized, that doesn't come out of the académie (the MFA system). Hence my stronger interest in comics this year, for example.

But part of it is simply that art books I read in the specific fields listed above tended to be older. For instance, Words for Art: Criticism, History, Theory, Practice

Still, there is something about this list of books that probably reflects some of the issues that made me quit writing this blog (for the most part). I only want to read what I like to read, and I only want to look at art that gives me pleasure. That inherently narrows the field. To write a good art blog, you have to be willing to engage everything, and I did that for years before I got tired of it. And in a way, this reading list reflects that.