The world of art galleries is divided into seasons. I don’t say “the art world” because I consider the gallery world to be a small subset of the art world. But traditionally, we have a fall season that starts just after Labor Day and a spring season that starts just after New Year. Summer is traditionally a dead season. (The bookselling world is divided the same way, as are school years.) I think this comes out of the New York City art gallery world, although I may be wrong. The idea was that everyone was on vacation during the summer, so it made no sense to open your big shows after Labor Day. Why this should be as true in Houston as it is in New York, I don’t know. But for a long time, we got “fall collections” of warm clothes utterly inappropriate for the volcanic heat of Houston—we take our cues from New York, whether it makes sense to do so or not.

I started my personal fall art season by visiting Foltz Fine Art, the Menil Museum, the Art League, and ARC House on Friday. Let’s go through them one by one. There will be a lot of photos in this post and not much criticism. First, let’s look at the large group show at Foltz, The Show is called Texas Emerging: Volume II and featured a lot of work by six artists: Erika Alonso, Dylan Conner, Laura Garwood, Peter Healy, Matt Messinger, and Meribeth Privett. Of these six artists, I was only really familiar with Conner and Messinger, both of whom I have pieces by in my personal collection.

Connor’s work is sculptural, made with salvaged metal and creamy white polymer gypsum. The salvaged metal often has a patina or layer of rust.

I know from experience that the works are quite heavy, but what I like about them is their elegance and almost biological.

Dylan Conner, Wasteland Coral, 2019, steel from pipe with natural patina, polymer gypsum, reclaimed foundry equipment with refractory residue, partially charred hardwood timbers from pallet, and steel hardware

Dylan Conner, Wasteland Coral, 2019, steel from pipe with natural patina, polymer gypsum, reclaimed foundry equipment with refractory residue, partially charred hardwood timbers from pallet, and steel hardwareThese pieces are like pieces of random metal with abstract polyps growing out of them. And I was astonished to see them in Foltz Fine Art, since I have always thought of it as a gallery that specializes in midcentury Texas artists (like Richard Stout and Stella Sullivan, whose retrospective show I reviewed in Glasstire in 2018) and landscape art. But looking at their recent exhibits, I see that more and more of the shows have featured contemporary artists. I hope that they don’t lose their focus on early Texas modernists because they are the only commercial gallery that makes an effort to remember our regional art history. But I approve of them showing younger artists.

I missed Texas Emerging: Volume I, which going by what is on the Foltz website must have been fantastic and perhaps even more daring than this iteration of the show. Most of the artists this time around are painters (Conner being the major exception, though several of the artists have at least some three-dimensional works). I have nothing against painters, of course, and I don’t expect Foltz to start showing installation art or video art anytime soon.

One of the artists I had never heard of was Meribeth Privett, who does these large, gestural abstractions. I’m always a little surprised when I see an artist in 2021 doing abstract expressionist painting, a style that reached its zenith 60 odd years ago. But while we are mostly well and truly over post-modernism, one thing that it gifted us was to tell is that the entire history of art was ours for the plundering. If what you want to express is best expressed with a more-or-less defunct art style, go for it!

I know nothing about Privett, so I went to her website. In addition to painting, she offers up her services as a “creativity coach”. OK, I’m not exactly sure what that is. Which probably means I could use some creativity coaching.

Laura Garwood, left: Untitled (burgundy, red yellow, white), 2019, right: Untitled (Dark purple, Yellow, Pink Stripes), 2018, both are oil and acrylic on canvas

Laura Garwood, left: Untitled (burgundy, red yellow, white), 2019, right: Untitled (Dark purple, Yellow, Pink Stripes), 2018, both are oil and acrylic on canvasBarnett Newman called and wants his sublimity back. Laura Garwood is another artist I’ve never heard of. I used to have at least an inkling of pretty much every artist in Houston, but as time (and isolation) goes on, I know fewer and fewer of them. One great thing about going to all these openings was that I got a chance to reconnect with a bunch of them.

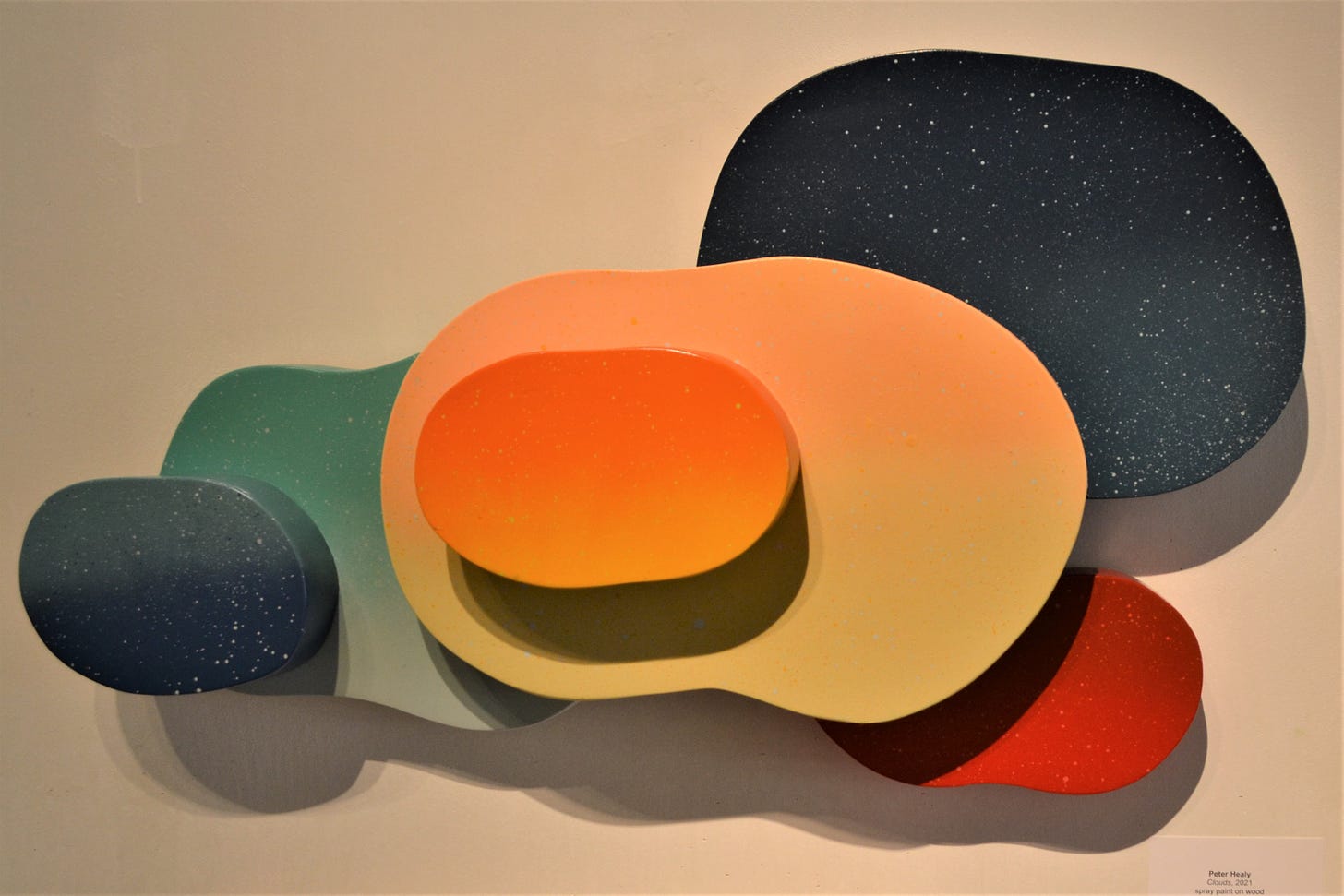

Peter Healy is another artist I don’t know personally, but I think I’ve seen his work around. As far as I can tell from various crumbs online that I’ve found, he is based in Houston but is from Northern Ireland. All of his pieces in this show were fun and attractive. Assemblage #1 is made of “found wood”, but despite that, it looks quite slick and polished compared to other assemblage artists (I’m thinking of Wallace Berman, George Herms or, here in Houston, Patrick Renner). I prefer my assemblage to feel a little more rough-hewn, a little more “street”, but Healy’s assemblages are attractive.

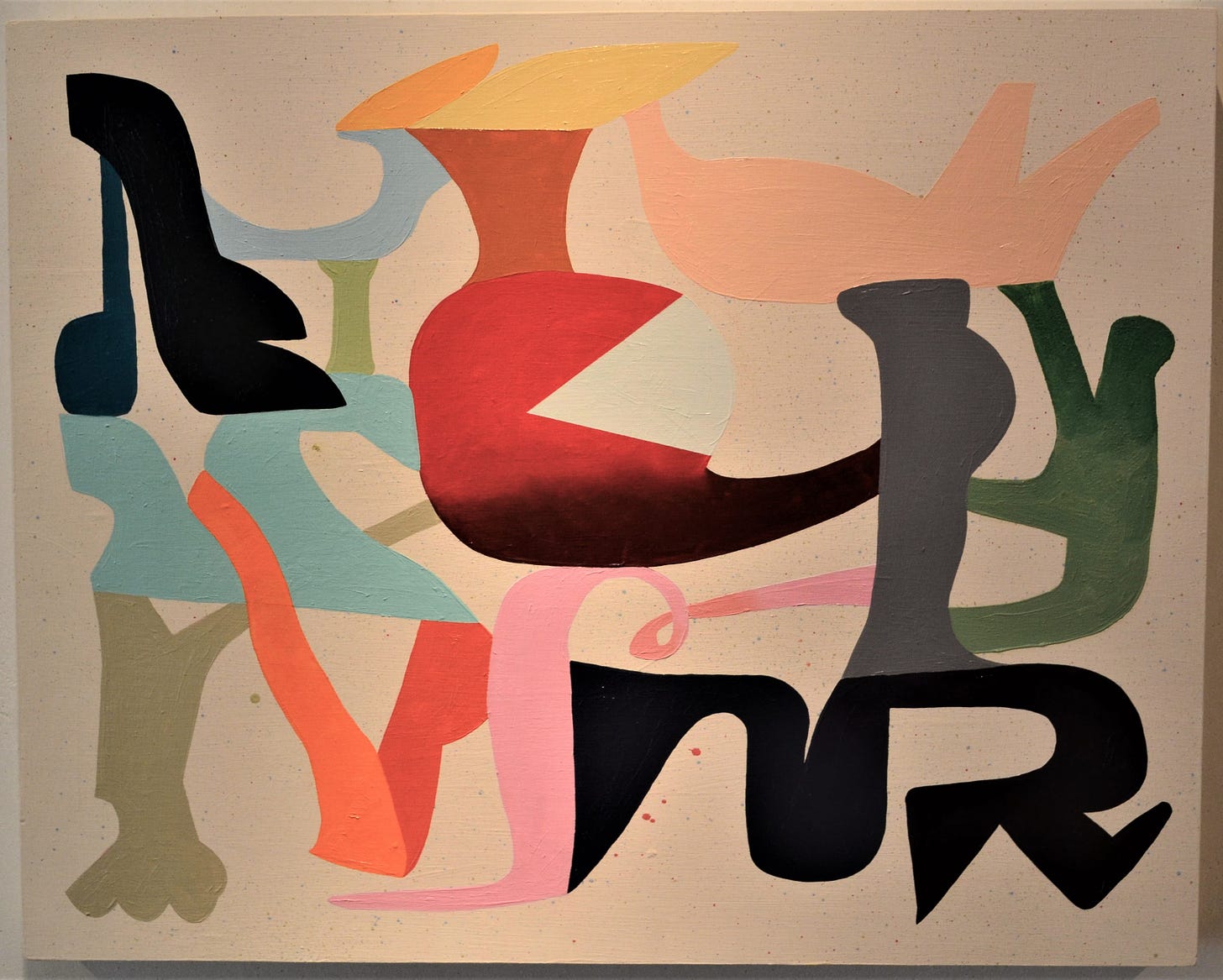

Healy is also a painter, producing jaunty abstractions.

These have the feel of midcentury illustration in a way.

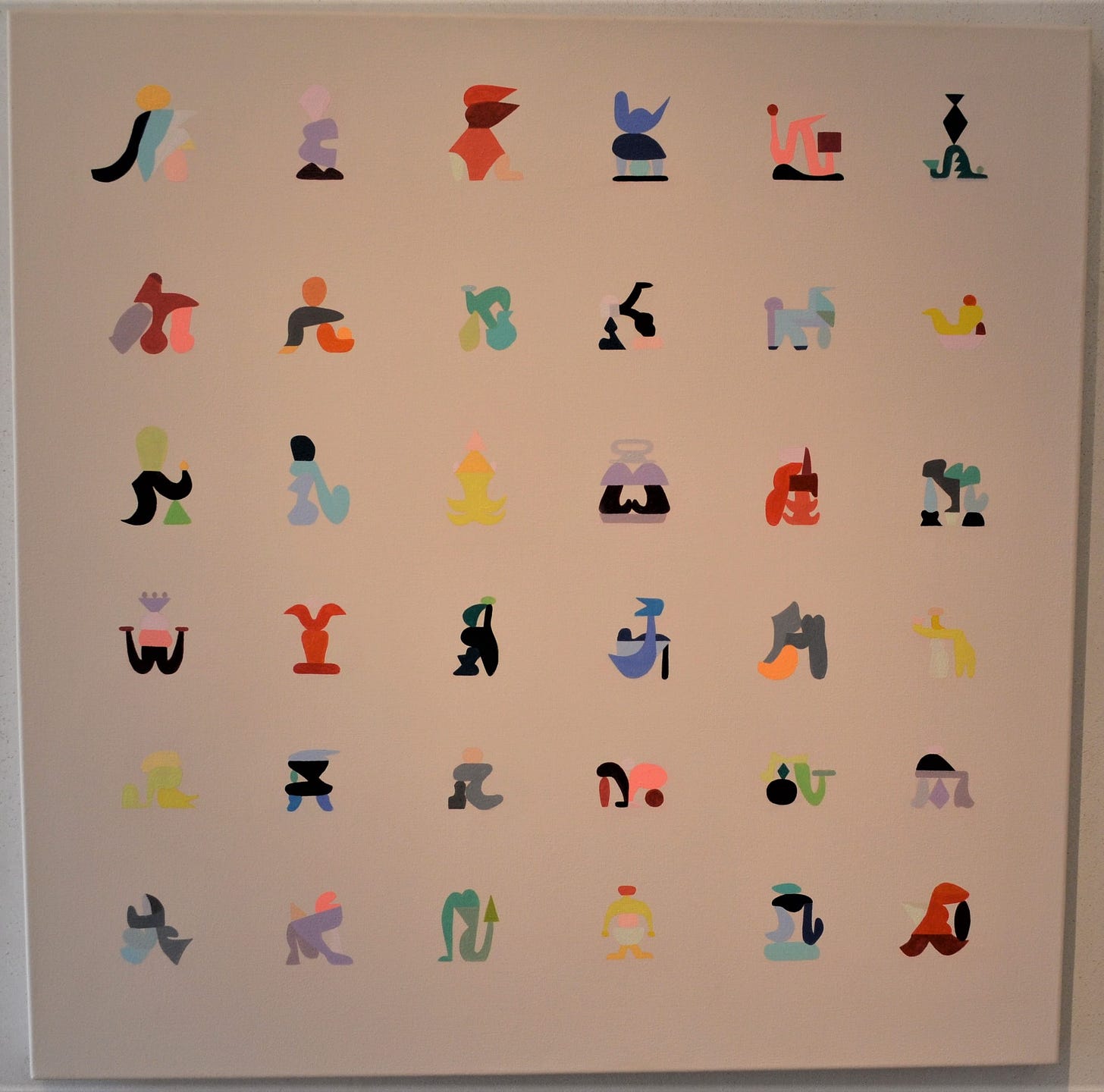

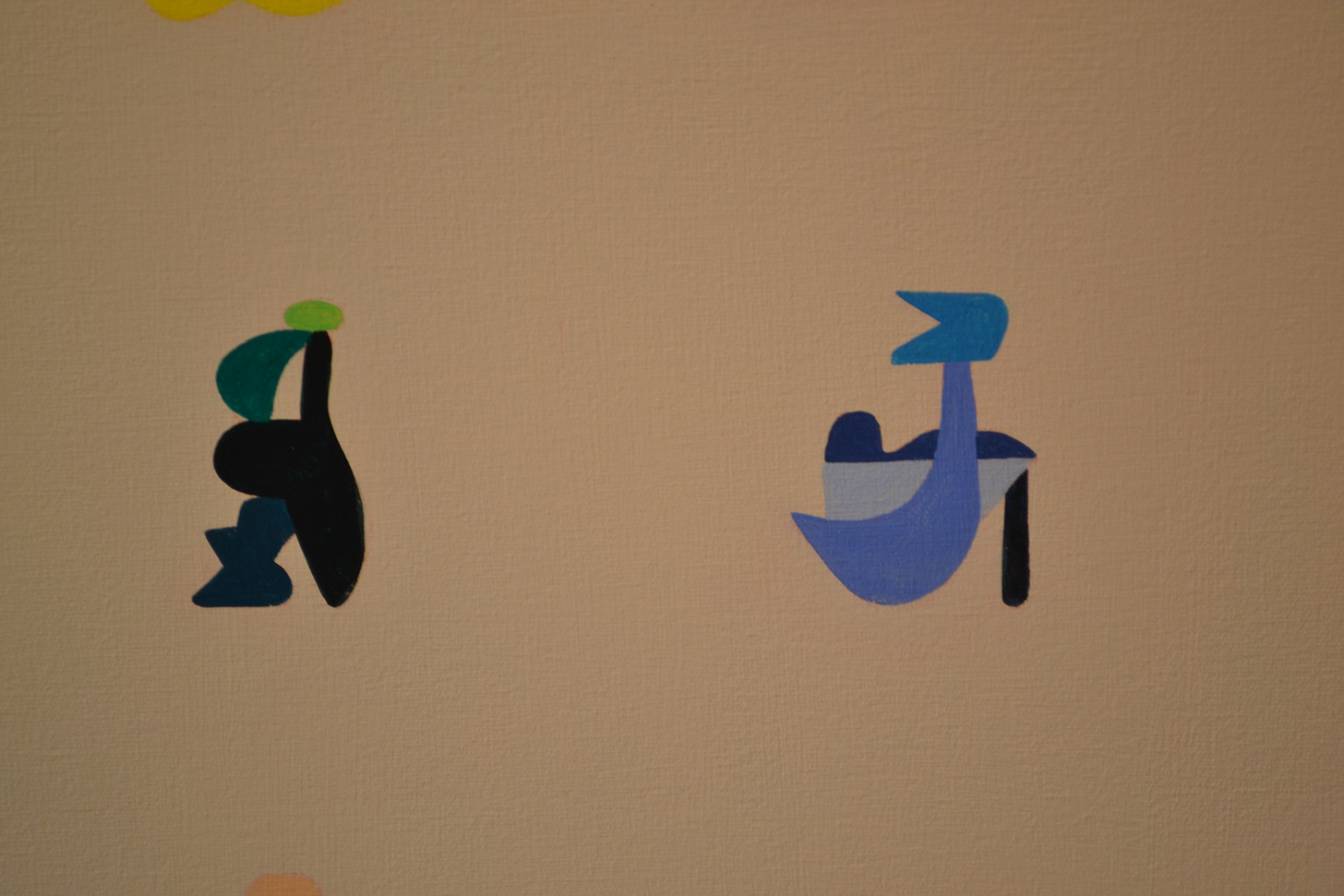

Community #2 is like a model sheet for little abstract figures for an animation.

Having seen the model sheet, I want to see the story that they star in.

This piece made with found wood has that rough hewn quality that I like.

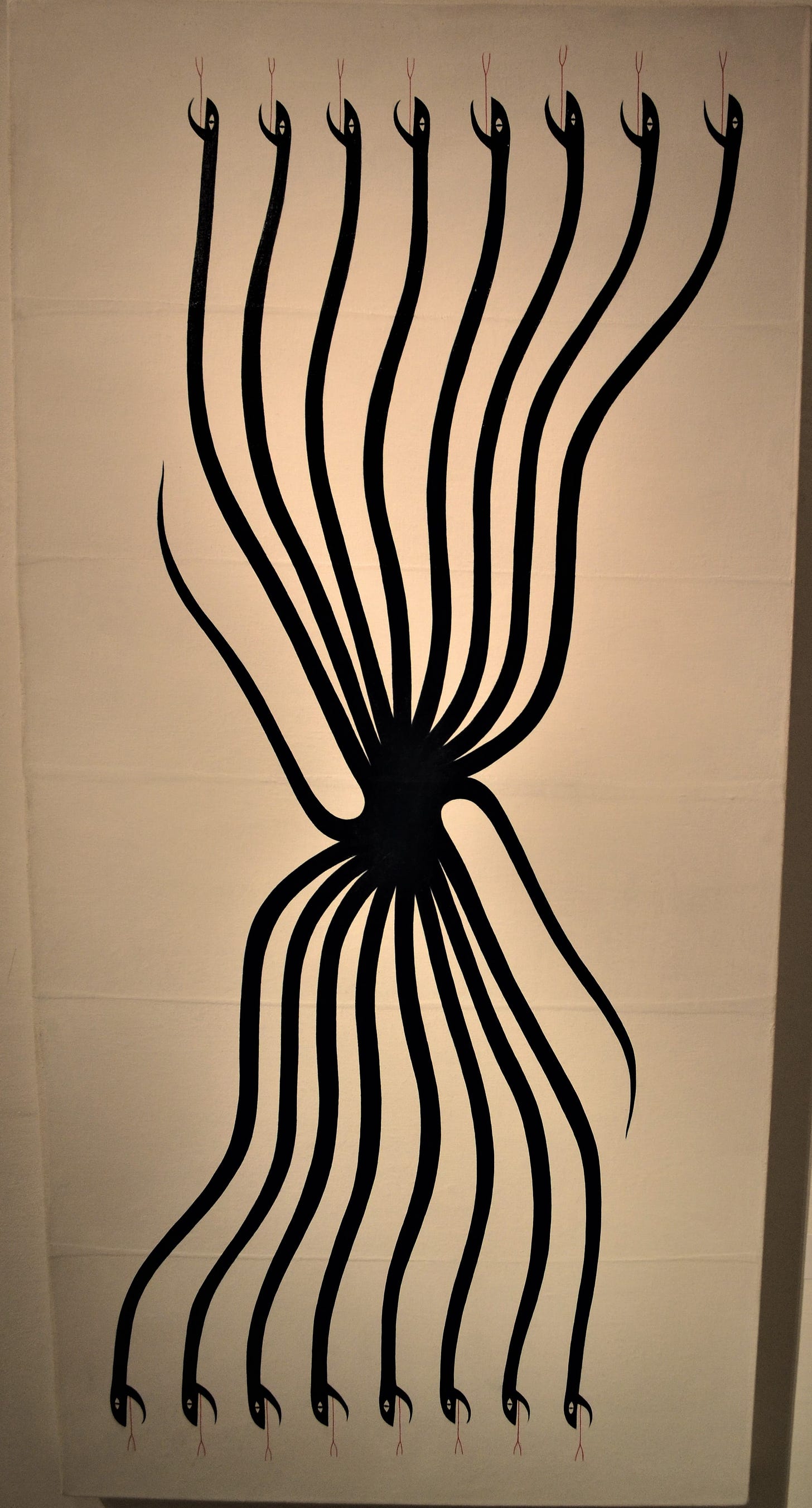

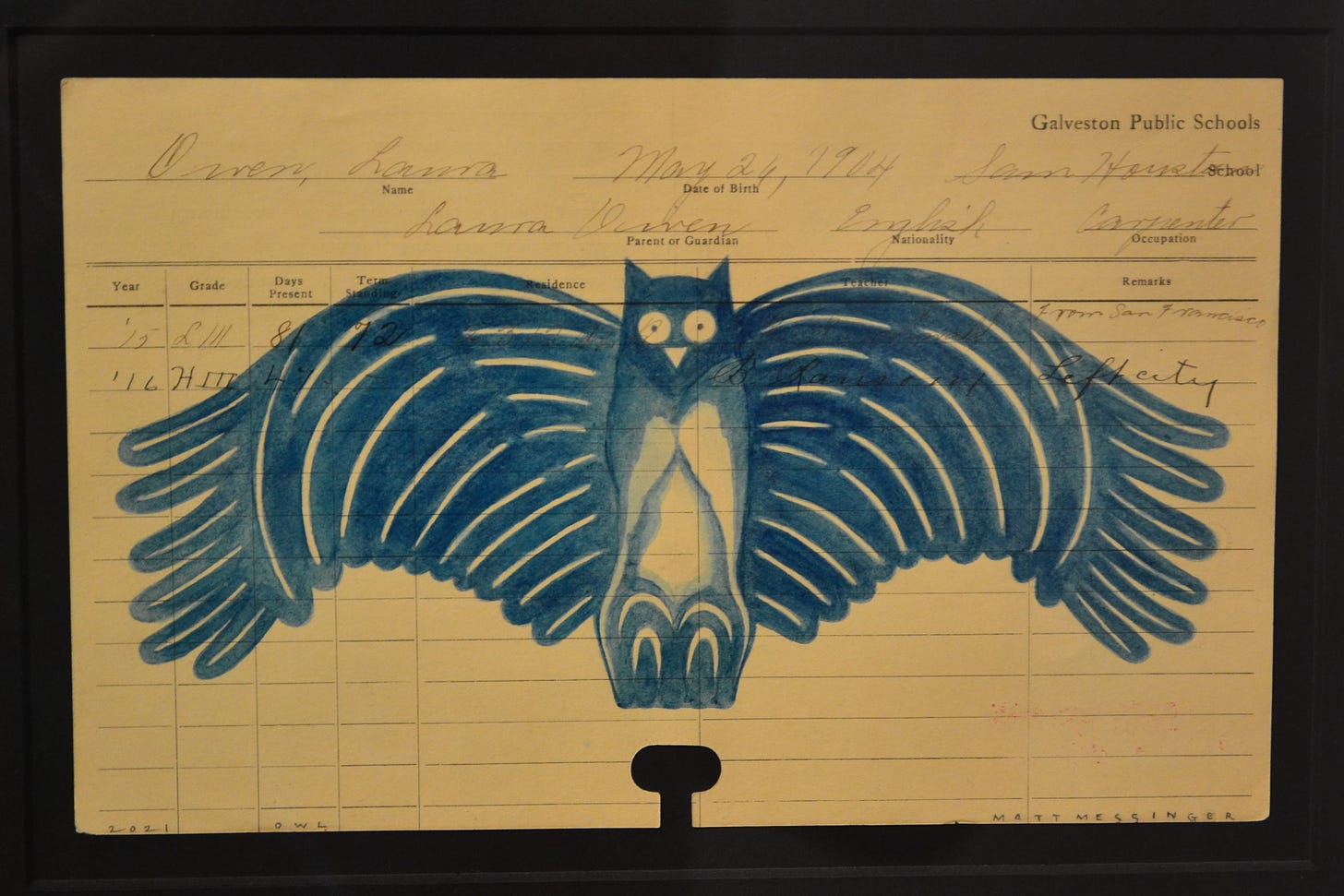

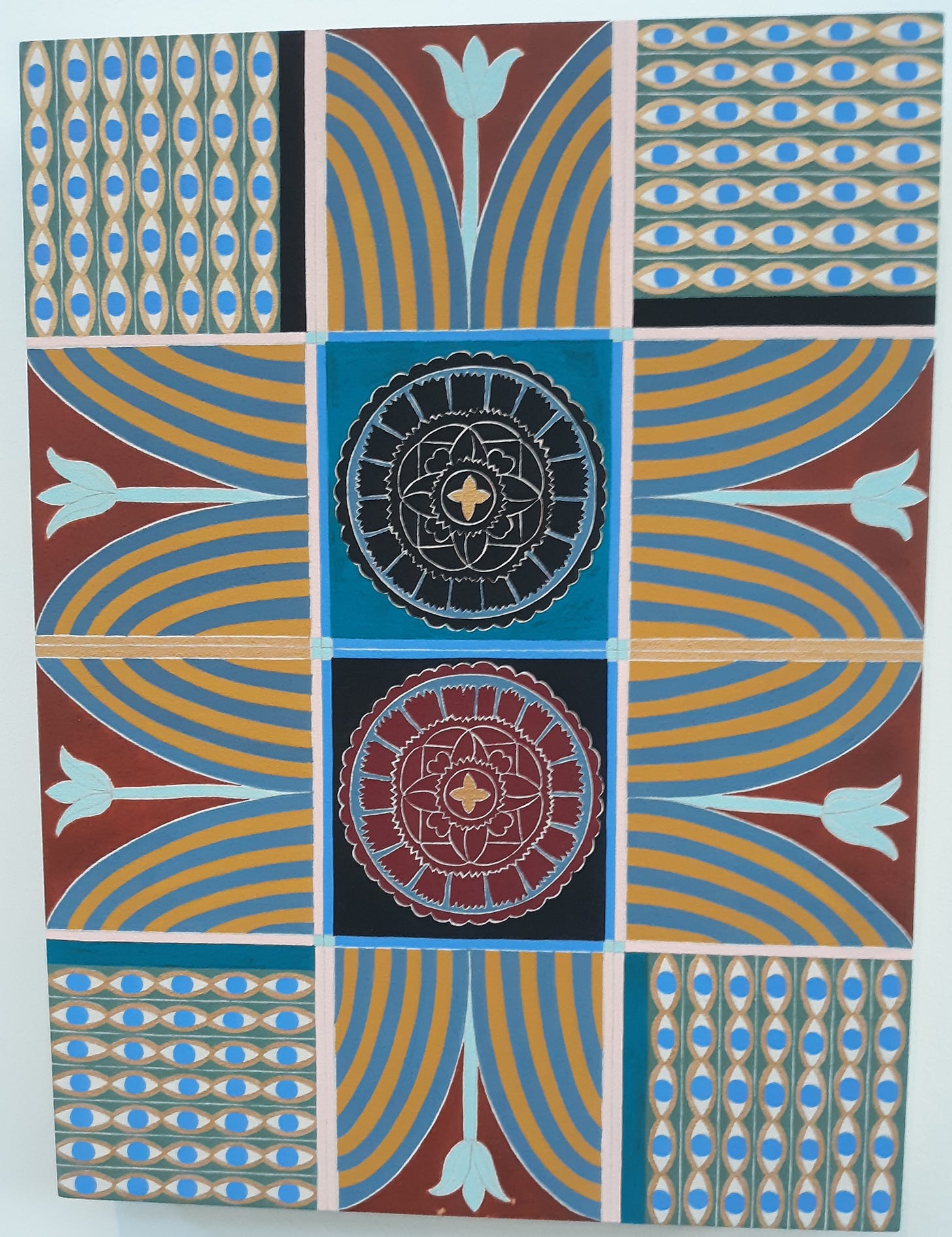

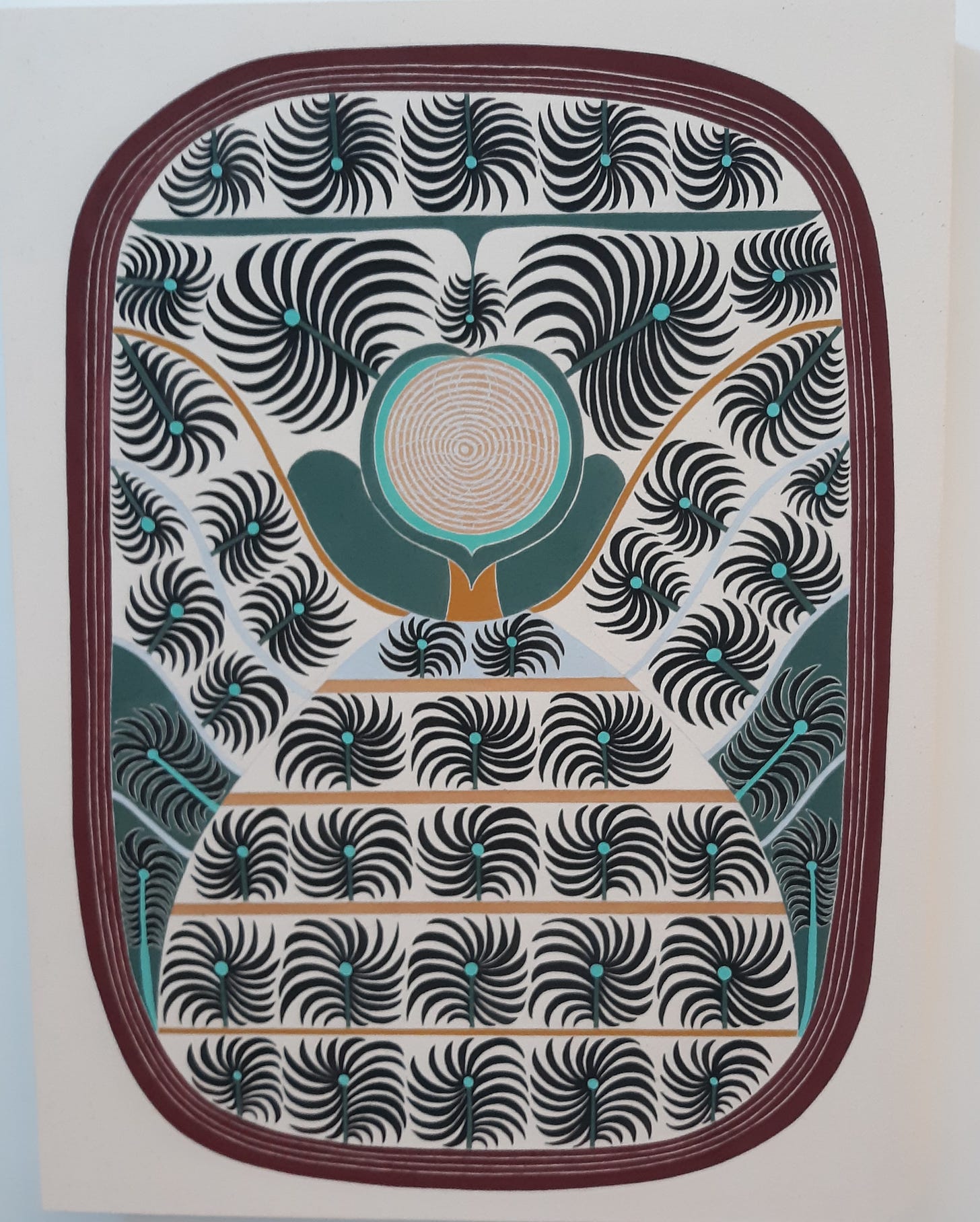

Matt Messinger is an artist I know personally. From where I sit, I can look at a painting/collage that he made. I remember first seeing his work at the 2011 Big Show at Lawndale. He has been around in the Houston art scene but has never gotten the recognition that I think he deserves. For this exhibit, Foltz Fine Art gave him his own room within the gallery.

Messnger uses all the space in this little room to show his art. Imagine having the Serpent Rug on the floor of your home. Would you ever walk on it?

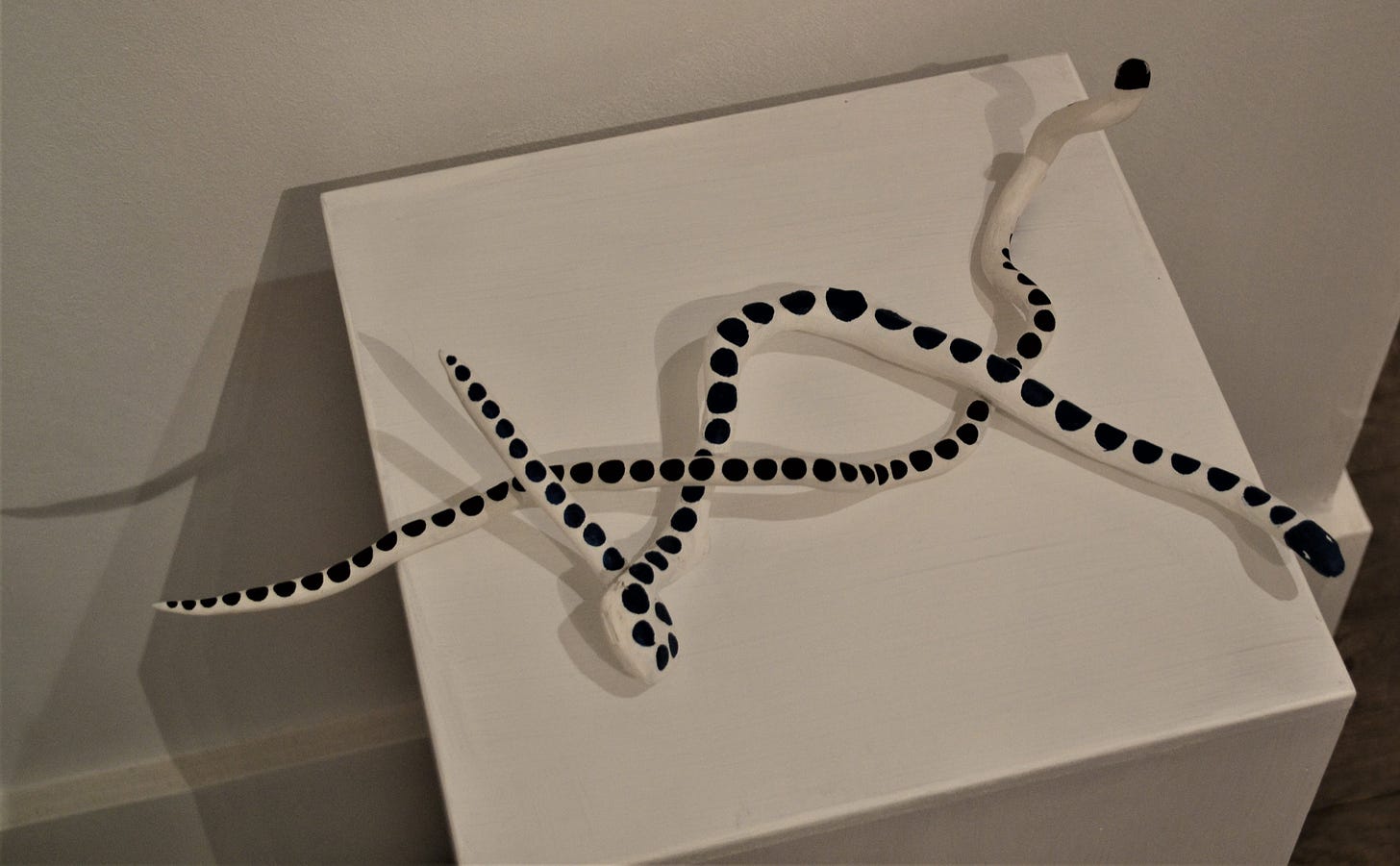

The first work I saw by Messinger seemed to reference quite old pop culture (the piece I own is a silhouette of a Fleischer Brothers’ Popeye, a cartoon series that was produced in the 1930s). But nowadays, Messinger seems to produce mostly animals and mythological beasts, in a way that suggests totemic use.

OK, I suspect that Theodore is not a totemic spirit animal. I’m guessing he is just a house cat. \

In addition to these works on paper and paintings, Messinger also produces three-dimensional work, often assemblage based.

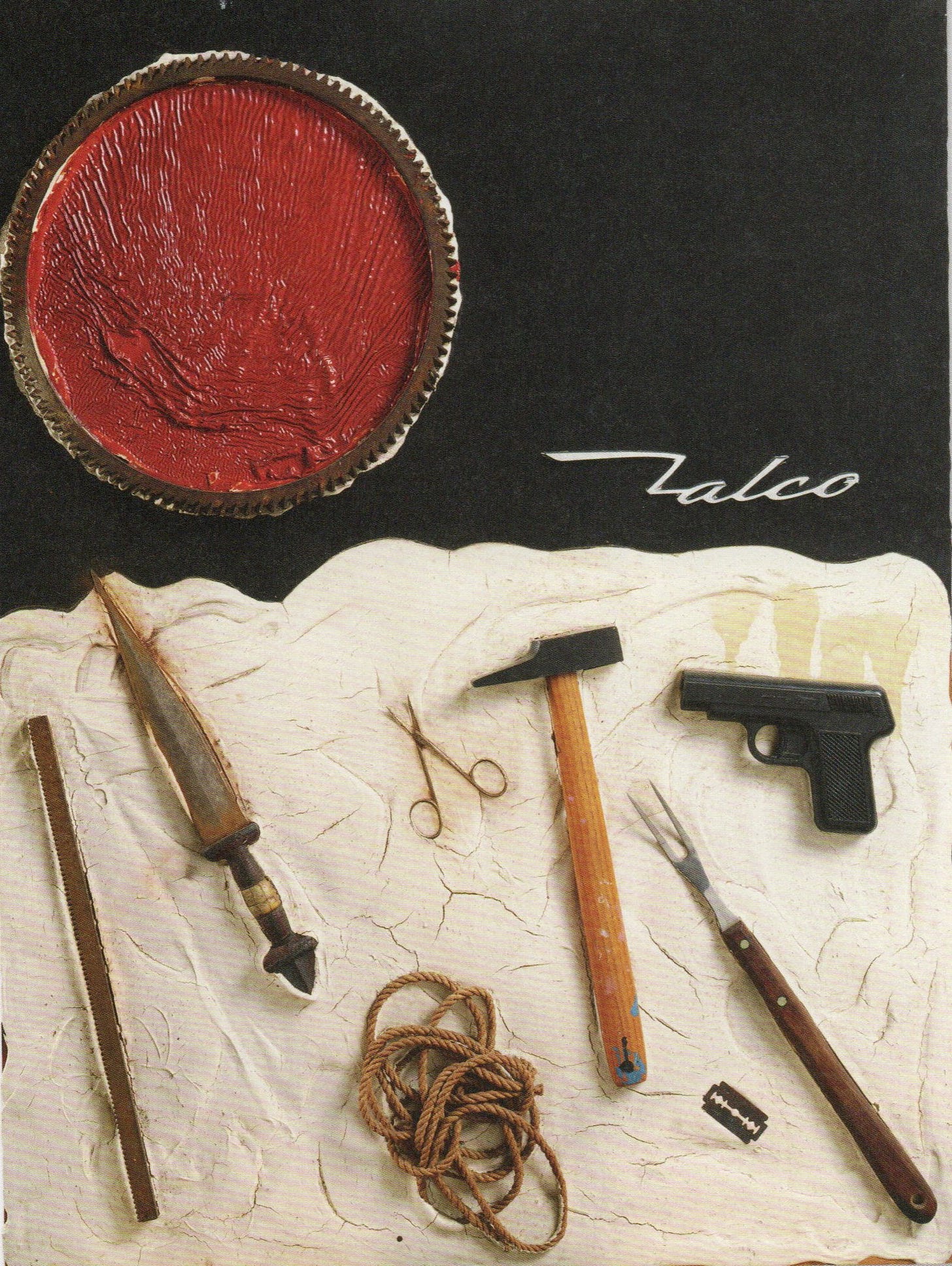

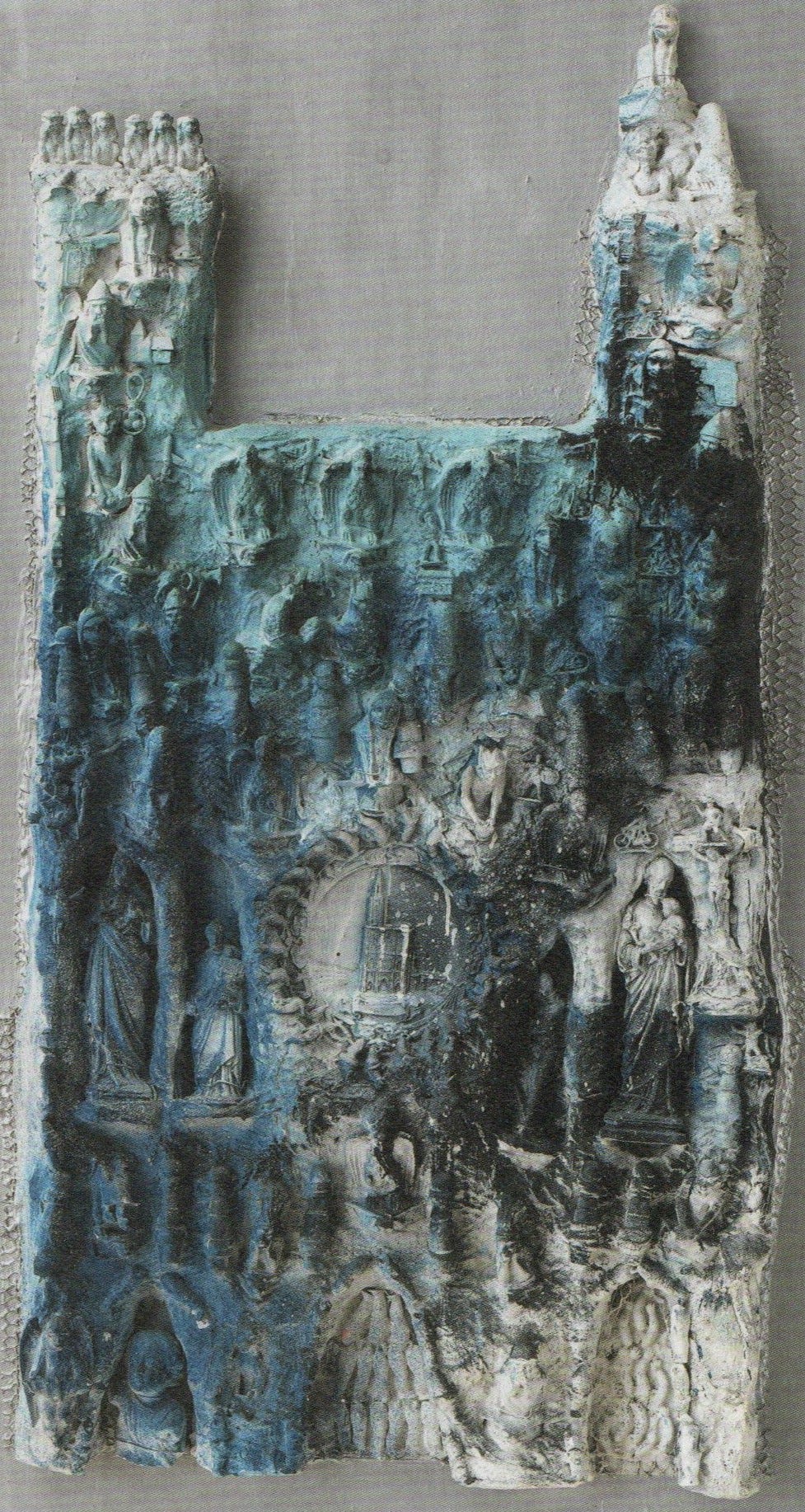

After I visited Foltz Fine Art, I went over to the Menil Museum to check out Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s. Niki de Saint Phalle was one of the artists in Nouveau réalisme movement in France that started in 1960 which included such artists as Yves Klein, Arman, César, Mimmo Rotella, and Christo. It is often seen as the French version of Pop Art, though with Yves Klein and Christo, it doesn’t feel all that Pop. And really, the work by Niki de Saint Phalle in this show seems, at best, tangentially related to Pop.

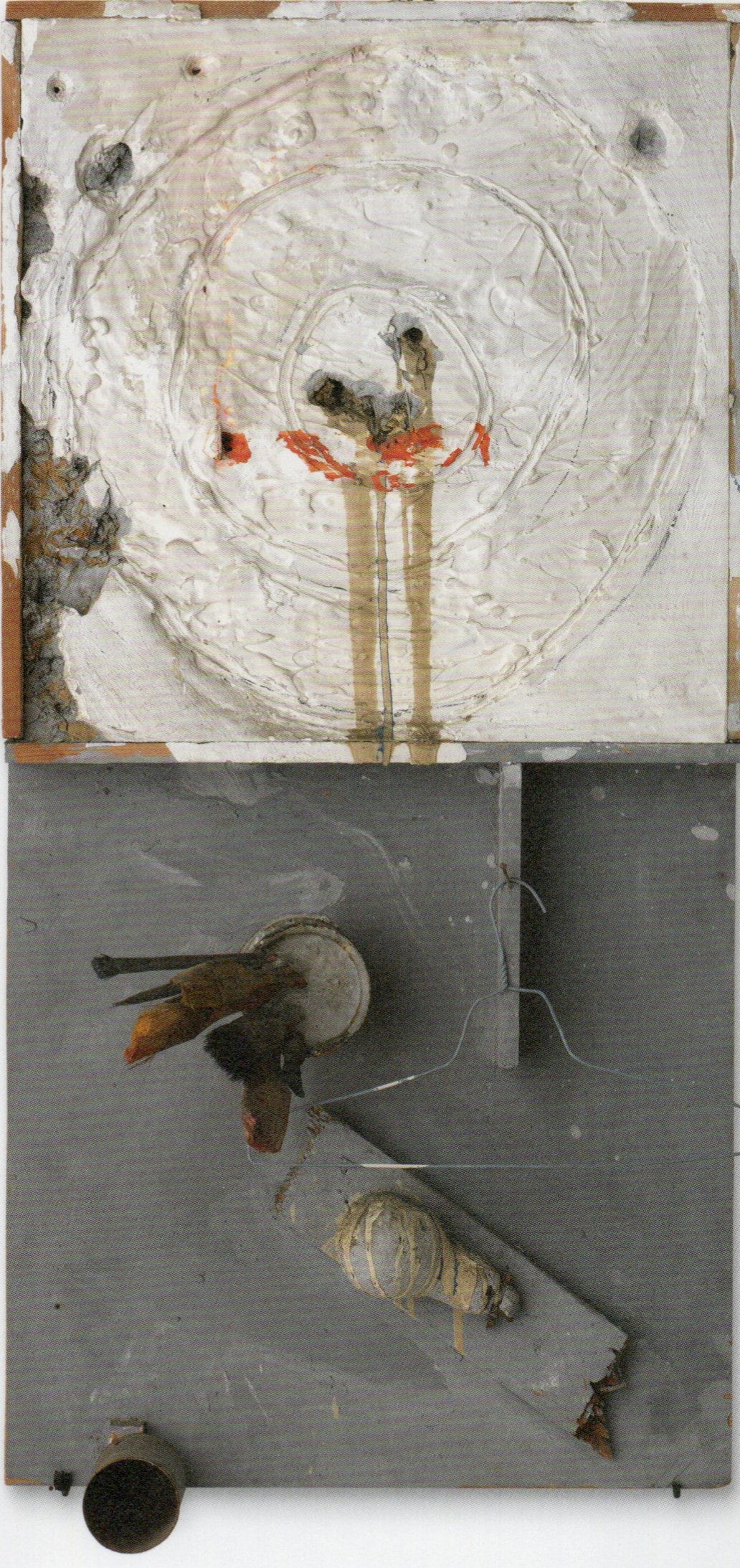

One thing that was in the air at the time all over the Western World was assemblage. I was reminded of Robert Rauschenberg looking at Tu est moi.

One series of works she did in the early 60s were called Tirs. “Tir” is French for “shot”. Saint Phalle would build plaster constructions with bags of paint on them then shoot them with a rifle wo let the paint run down over the painting. She often invited other artists to participate in the shooting part. In this example, she takes one of the most famous images that Jasper Johns painted repeatedly, the target, and used it as an actual target. She made four bullseyes as well as a large number of bad shots. The lightbulb and can with paintbrushes directly refer to specific works by Johns. It seems perfect that Saint Phalle took Johns idea of a target for its intended purpose. Johns took something that had no aesthetic value—a target—and turned it into art. Saint Phalle returns it to the world by shooting it.

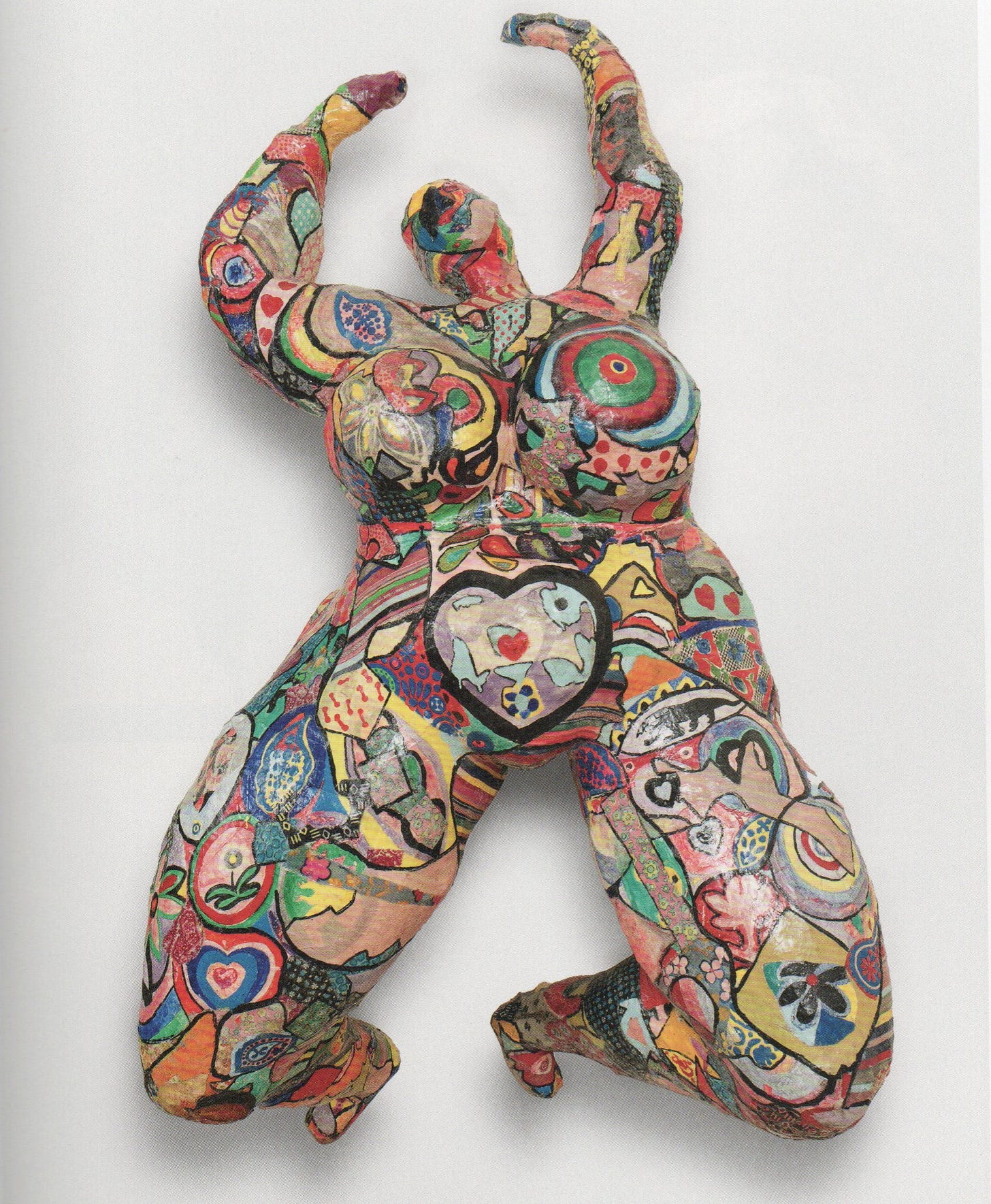

Lili ou Tony is an examples of Saint Phalle’s series of giant, colorful female figures called “Nanas.” She started doing Nanas in the mid 1960s. Perhaps the most famous Nana was Hon, created in 1966 in the Moderna Museet de Stockholm. Here the Nana was gigantic, on her back, with her legs spread, and an entrance at Hon’s vagina that visitors could enter. I’m curious to know what was inside Hon. Unfortunately, they did not attempt to reproduce Hon for this exhibit.

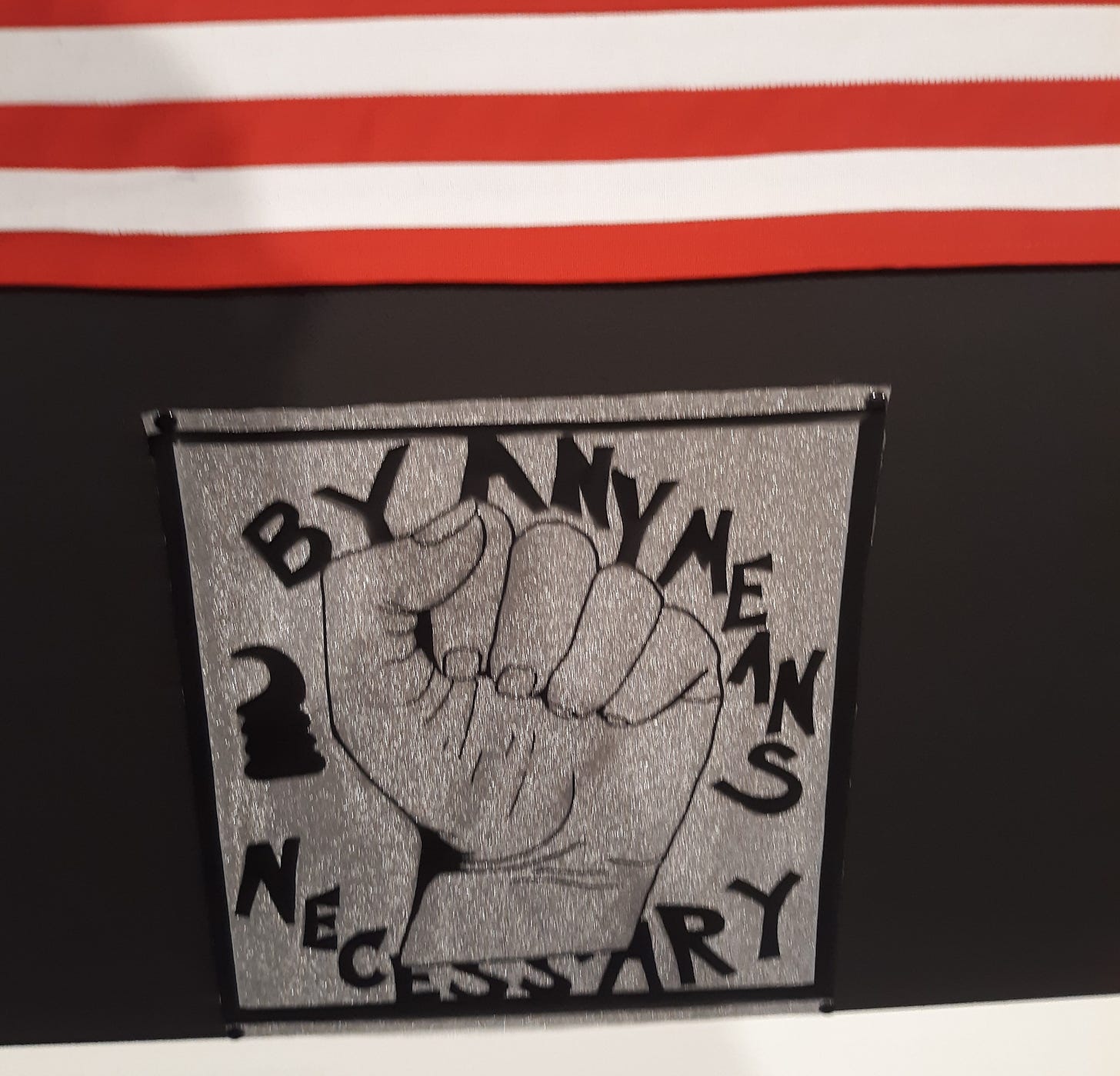

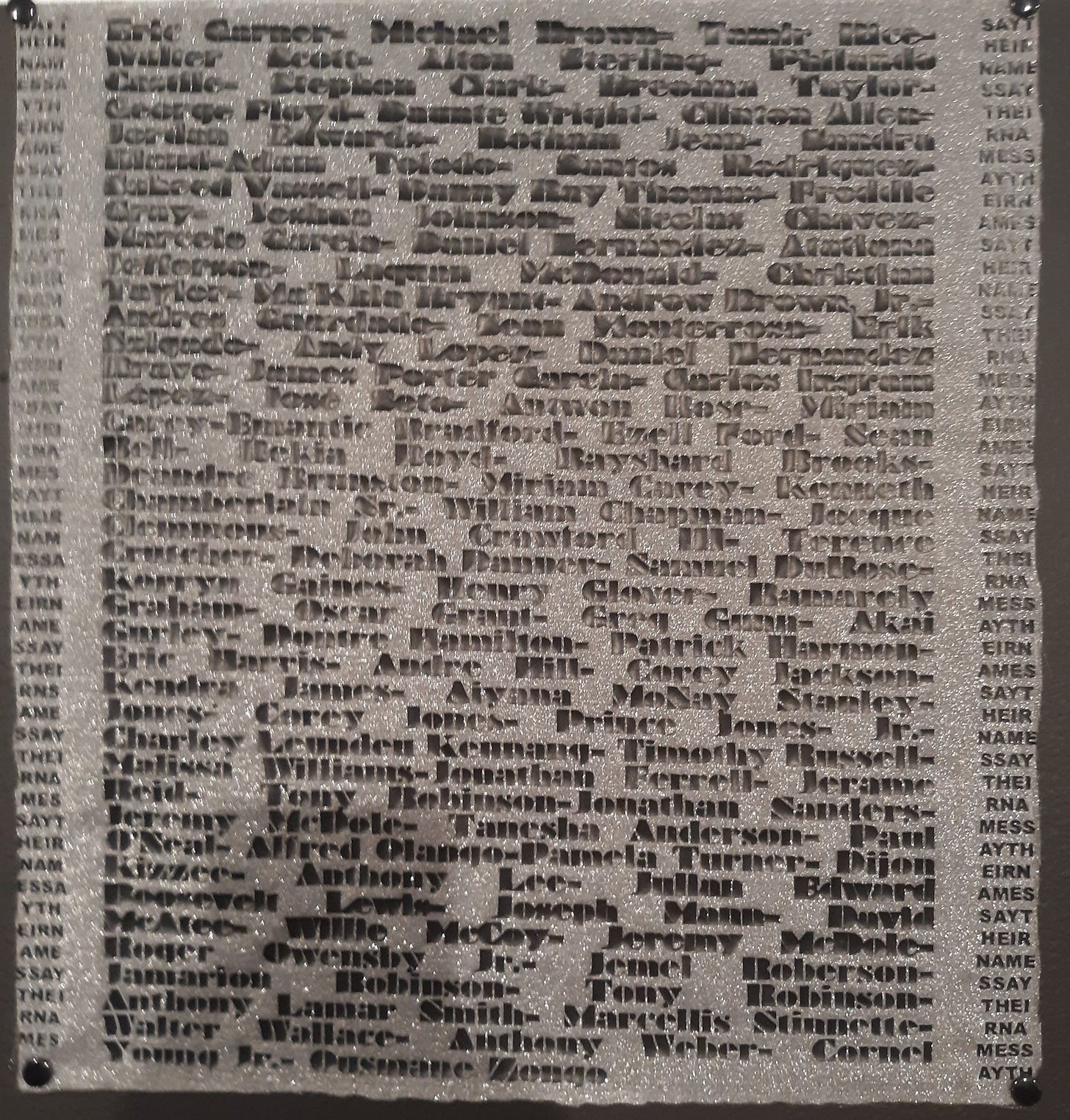

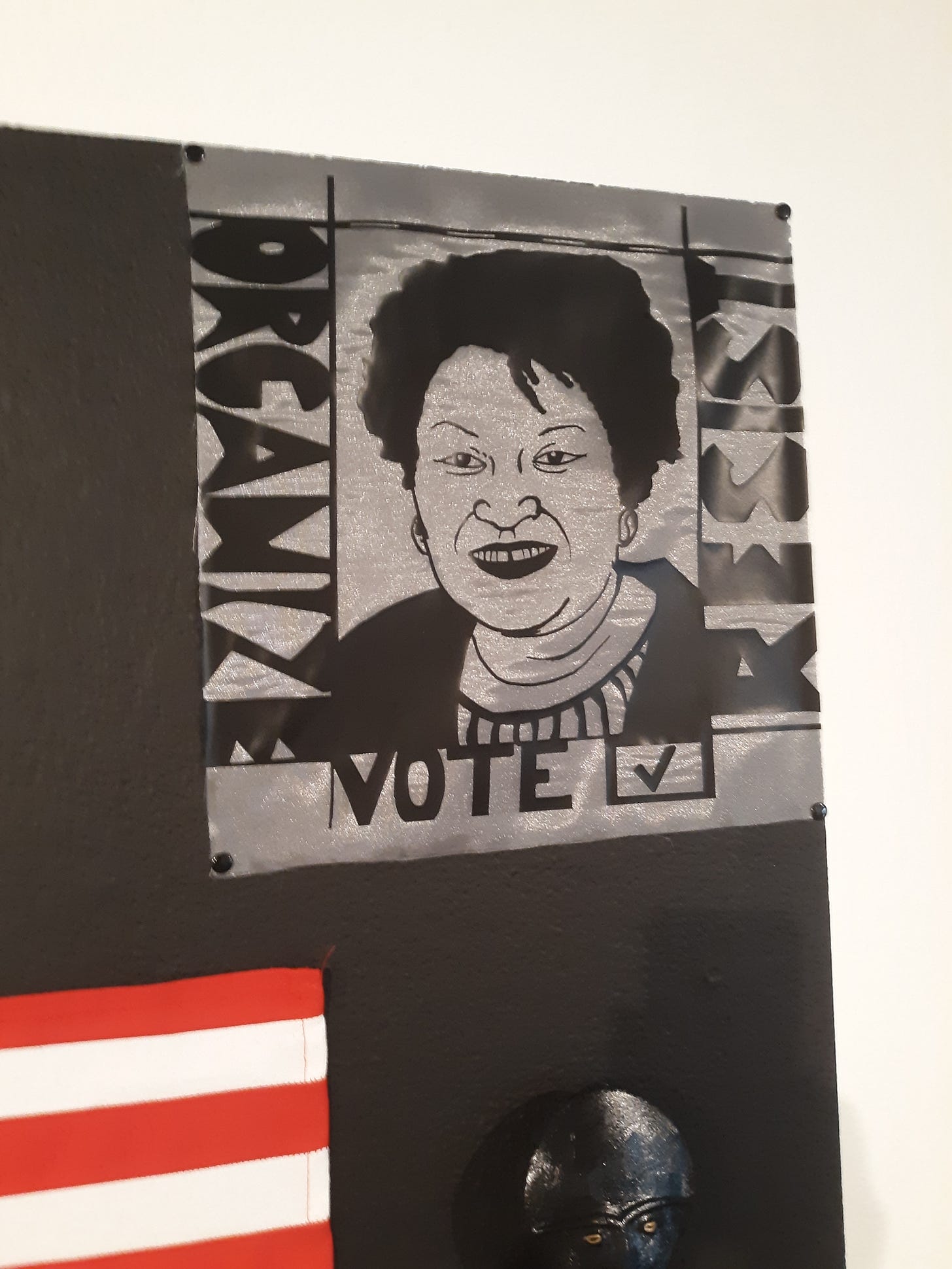

Vicki Meek is the 2021 Texas Artist of the Year at the Art League Houston. Every year they pick an artist (or a collective, as when Havel & Ruck were honored in 2009) for the honor. I don’t know all that much about Meeks. I saw an exhibit she curated at Project Row Houses a few years ago, Life Path 5: Action/Restlessness, back in 2009. But “curated” is the wrong word. Meek collaborated with all the artists on their installations. But aside from that one exhibit, I haven’t seen much of her installation-based artwork. One cool thing about the Texas Artist of the Year exhibits is that the Art League publishes a small monograph about the selected artist. So now I have a book about Meek to catch up on her work. For the exhibit, there are several large works, some of which are wall art but closer to installation in their polyvalence. For instance, Elizabeth Catlett Political Prints & Sculptures Reimagined features not only a central image of a stretched out American flag, it features also African sculptures on two small shelves on either side of the flag, with reimagined political posters above and below the flag.

And what makes it even more installation-like is that it faces an almost identical piece on the opposite wall. Identical in format, but the surrounding political prints are different.

There are more large installations in the front gallery.

This is a recreation of an older piece. Standing in the background are artists Jake Margolin (left) and Nick Vaughan (right), who were out with their extremely energetic baby. One of the reasons I like these openings is that I get to catch up with old friends. The last time I saw either of these two artists was before COVID, before they had a son to drag along to exhibits.

From the Art League, I drove over to ARC House for a small Catherine Colangelo show. ARC House is a private house built on stilts after Harvey to be relatively flood resistant. They have been hosting art exhibits for several years now.

This exhibit showed mainly older works by Colangelo. A week later, a show of her new work opened at Front Gallery.

And as with many of the exhibits, I got to speak with artists I hadn’t seen in over a year. I saw Catherine Colangelo, of course, but also Tudor Mitroi, who has had an exhibit at ARC House early in 2020, before COVID shut everything down.

Those were the exhibits I visited on Friday, September 10. In Part 2, I look at what was happening on Saturday.