by Robert Boyd

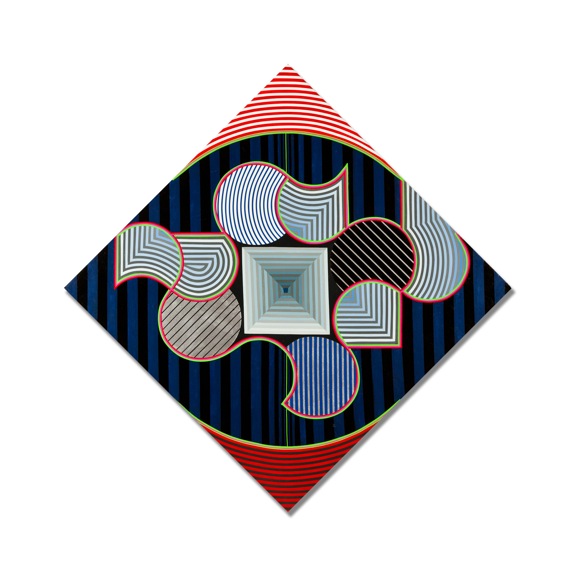

H.J. Bott, Roar Shock Well, 2012, glazed co-polymer vinyls on canvas, 36" x 36". (all photos courtesy of the Anya Tish Gallery)

In the center of H.J. Bott's painting

Roar Shock Well are four spaces filled with a skein of fine lines. The lines that fill each shape are different. They have a pattern, but there appears to be a certain randomness as well--or at least a pattern that the viewer can't discern. The lines that make up these patterns are exceedingly fine. In fact, as far as I can tell, all the lines and curves inside each of the four shapes are differently scaled parts of Bott's "Displacement of Volume" shape.

"Displacement of Volume" or DoV is a geometric form that has been appearing in Bott's paintings and sculptural objects since 1972.

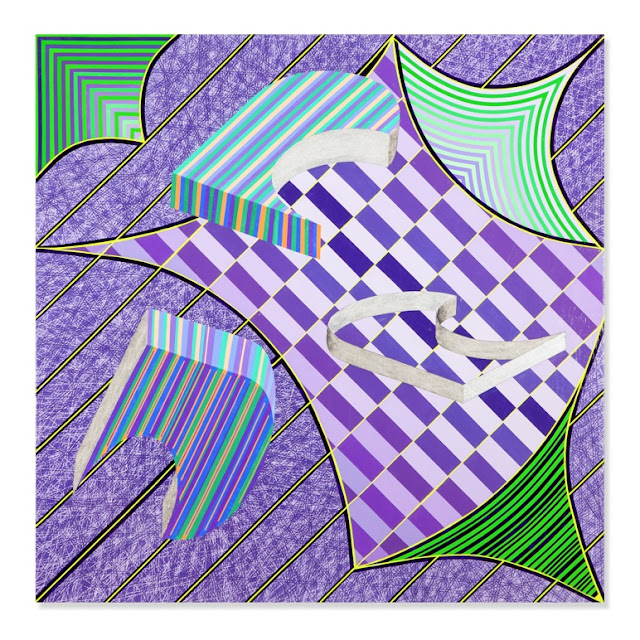

H.J. Bott, Fleur de Enclume, glazed co-polymer vinyls on canvas, 20" x 20"

Bott may have used DoV to create the fine-line patterns in this recent group of paintings (on view at

Anya Tish Gallery through June 9), but the viewer experiences it as an intensely-colored texture. DoV is something that is obviously important and highly meaningful to Bott. But there is no obvious reason that we, as viewers, should care about it except insofar as it is the tool Bott uses to make these paintings.

But I'm going to suggest that beyond whatever meaning that DoV has for Bott, it is interesting that he has created such a rich body of works out of it. DoV is a

constraint on Bott. He has chosen to limit himself to working with a single shape over and over again. Or to put it another way, he has turned his back on total freedom, the birthright of any painter since about 1900. Instead of enjoying that freedom with a painting like

Fleur de Enclume, Bott willingly slips on a straitjacket of DoV. You have to ask yourself why.

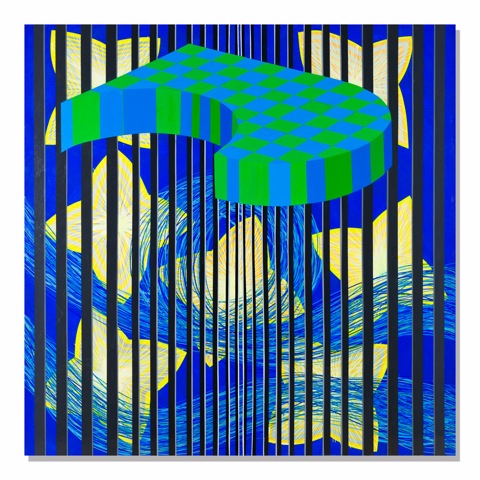

H.J. Bott, Hip Hop Core, 2011, glazed co-polymer vinyls on canvas, 43" x 43"

I think the answer is that a constraint can be an immense boon to creativity. This has always been known in poetry. Sonnets, villanelles and haikus have very strict constraints on number of lines, meter, line lengths and so on.

Oulipo created new constraints for writers in the 60s. But if we look at 20th century art, artists are constantly taking the gift of total expressive freedom and turning their backs on it--limiting themselves by form, by materials and in other ways--think Mondrian, Ad Reinhardt, Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, various minimalists, etc.. Bott is taking a constraint, the DoV, that on the face of it is inherently limiting, and uses it as a means of

increased expression. So a painting like

Hip Hop Core radiates a relative calm compared to the jittery

Fluer de Enclume, where the near symmetry makes the work feel like it should be perfectly balanced--except that it isn't.

H.J. Bott, Polchinski Perturbations, 2012, glazed co-polymer vinyls on canvas, 36" x 36"

In some of Bott's paintings, DoV floats out to become a three-dimensional image. Paintings like Polichinski Pertubations remind me a little of the work of

Al Held--but Bott is far more antic. That this mostly blue-violet painting has a black-and-green corner speaks to Bott's willingness to push his colors as far as they can go. It wouldn't be wrong to call the work in this show psychedelic.

H.J. Bott, BeyondBar Symmetry, 2012, glazed co-polymer vinyls on canvas, 30" x 30"

Like psychedelic art of 60s rock posters, Bott plays a little with placing two different colors with similar brightness next to each other. The blue and green in the solid DoV in

Beyondbar Symmetry vibrate. A majority of the pieces in this exhibit are square, which also links them back to a certain kind of art that flourished in the 60s and 70s--album cover art. It is possible to see each of these as an album cover for a psychedelic or prog band, like Traffic or Yes. Does it diminish the work to suggest this connection? I don't think so--abstract art doesn't exist in an abstract, impersonal world. It exist in

our world, and connects to our culture in not-always-predictable ways. If this work makes you think of, say, a particularly angular Robert Fripp guitar solo, that just adds to its richness.

H.J. Bott, Mesocarp Mischief, 2012, glazed co-polymer vinyls on canvas, 48" x 72"

In any case, Bott himself makes all sorts of associations. Just look at his titles--they reference fruit (

Mesocarp Madness), physics (

Polchinski Perterbations), ninjas (

Shuriken's Mob), psychology (

Roar Shock Well), and, yes, pop music (

Hip Hop Core). His work makes you think of artists as diverse as

Von Dutch (Bott did auto pin-striping as a teenager) and Al Held. His generally cool colors have personal associations.

J.L. Borges, in his introduction to

Brodie's Report, wrote:

I have tried (I am not sure how successfully) to write plain tales. I dare not say they are simple; there is not a simple page, a simple word, on earth--for all pages, all words, predicate the universe, whose most notorious attribute is complexity.

H.J. Bott created a constraint, a shape that on its own looks "simple." And he uses this shape to create his own complex visual universe.