by

Robert Boyd

The

Hybrid Arts Summit was held in part at the

Austin Museum of Art, which was at that moment was exhibiting

New Art In Austin: 15 to Watch, a group show which the museum hosts every three years. I was in town for the Summit, so I took the opportunity to check out the show. Afterward, I decided to pick up the catalog. I noticed they had the previous three catalogs (2002, 2005 and 2008). Curious, I picked up all four catalogs. I packed them away and carried on with the activities of the day.

Later in the day, I was talking about the Austin scene with

Salvador Castillo, and he offered the theory that Austin is not a very congenial place for artists because there is not a very big collector base there. I countered that Austin certainly had its share of rich folk and well-off professionals--the prerequisite for a good collectors community. His theory was that there wasn't a long tradition of collecting in Austin the way there was in Houston. He wasn't the first person who had put forth a version of this theory.

Art Palace moved from Austin to Houston basically because it was too hard to run a successful commercial gallery in Austin.

I don't know enough about the Austin scene to know if this lack of collector support is due to an inadequate appreciation for art locally or if it's a simple game of numbers (Houston is four times larger than Austin, after all). There seem to be several commercial galleries there (I count something like

nine), and while no one starts a gallery with much hope of getting rich, they are businesses and the idea is to sell enough to cover your expenses with a little left over at the end. So either the gallerists in Austin are delusional and headed for bankruptcy or else they are successful-- or at least scraping by.

So you're an artist in Austin, and you're not too bad at what you do. Will Austin support you? I'm not talking about making a living exclusively off your art, nice though that would be. I'm talking about providing you with the means to live which should include being able to sell at least some of your art, hopefully to Austin based collectors. (As an aside, in

a panel discussion on Regionalism that was recorded for Glasstire,

Christina Rees said that Houston collectors collected the work of Houston artists to an unusual degree. I can't really compare Houston's collecting habits to other cities, but I do know that most Houston galleries--even the blue chip ones that show lots of out-of-town art--show at least some Houston artists. Maybe that's a problem for Austin artists. Perhaps Austin collectors are looking to New York or London or elsewhere for their art.)

With the four

New Art In Austin catalogs, I had the raw material to make an educated guess at how well Austin supports its artists. If you were an artist who was selected for the 2002 show, were you able to sustain a career in Austin? Or did you have to move away? On one hand, Austin is a relatively inexpensive and highly congenial place to live. On the other hand, art by Austin artists is so lacking in buyers that Art Palace moved to Houston.

Matthew Gutierrez, After-During I-V (detail), acrylic on four canvases, 2001 (from New Art in Austin 2002)

Matthew Gutierrez, After-During I-V (detail), acrylic on four canvases, 2001 (from New Art in Austin 2002)

So I decided to try to find out where the artists in the 2002, 2005, and 2008 exhibits were now. Were they still making art? Were they still in Austin? Out of the 65 artists in those shows, about 39 seemed to still be in most recently in Austin. The phrase "most recently" is important--of that 39, not all of them had been mentioned in Google-accessible sites recently. For many, the most recent mention was in 2009, and Matthew Gutierez, who was in the 2002 show, hasn't been heard from since 2002 as far as I could tell. If we look at each individual show, we get this result:

| Still in Austin | Not in Austin | % moved |

| 2002 Artists | 11 | 11 | 50% |

| 2005 Artists | 15 | 9 | 38% |

| 2008 Artists | 13 | 6 | 32% | | |

So over time, artists move away from Austin more and more. But this could possibly be said of artists anywhere, particularly young artists. And that is one feature of the

New Art in Austin exhibits--they feature emerging artists for the most part. Many of the artists are recent college graduates, and some are even still in school when they are selected for the shows. So they live in Austin because they studied there, but life--in the form of career, marriage, family, etc.--may pull them away over time.

Mark Schatz, Pastel Crash, crashed car, polystyrene foam, and interior house paint, 2002 (from New Art in Austin 2002)

Mark Schatz, Pastel Crash, crashed car, polystyrene foam, and interior house paint, 2002 (from New Art in Austin 2002)

Many move because they have gotten teaching jobs elsewhere.

Mark Schatz, (2002) for example, first moved to Houston and recently moved to Ohio to work at Kent State University. Of the artists that have moved away, at least five are teachers/professors. (Please keep in mind that all these stats are somewhat fuzzy. They represent the best information I could get through Google.)

Hana Hillerova, Swarm, installation with cardboard, plastic, paint, digital prints, 2004 (from New Art in Austin 2005)

Hana Hillerova, Swarm, installation with cardboard, plastic, paint, digital prints, 2004 (from New Art in Austin 2005)

So of the 26 that moved, where did they go? No particular surprises here. Seven went to New York. Five are in the Houston area. The rest are scattered to the wind--but often to college towns like Bellingham, WA, Cambridge, MA and Ann Arbor, MI. (None to Dallas or Fort Worth, as far as I could tell.) Two of Houston's best known artists were in

New Art In Austin shows--

Hana Hillerova and

Robert Pruitt.

Robert Pruitt, Great Scott, Iz She a Theef?!, conte crayon on butcher paper, 2001 (from New Art in Austin 2002)

Robert Pruitt, Great Scott, Iz She a Theef?!, conte crayon on butcher paper, 2001 (from New Art in Austin 2002)

All that said, a majority of these people are still in Austin, and as far as I can tell, a majority of the Austinites are still active artists. Austin is a great place to live, so even if it's hard for an artist to make a living there, these 39 stalwarts are making it work for themselves somehow.

One question I'm left with is this--is this rate of artist-exodus typical? If you took a random sample of youngish artists who exhibited in any other city in 2002, 2005 and 2008, would the results be much different? Do more artists leave Austin than other places? I don't know, so I am loathe to suggest that it is harder for an artist in Austin than in any other city.

However, I think it's true that if the collector base in Austin was larger and more willing to "buy local," that would give artists more of an incentive to stay. I don't think there is any special virtue in "buying local" in art--collectors should buy what they like, wherever the origin. But there are good reasons for a collector to buy work from local artists--you get the opportunity to meet them and get to know them, which is nice, and their work is often quite reasonable compared to out-of-town artists. In any case, if I were an Austin artist, I'd want to cultivate the local collector community, and would have a vested interest in seeing it expand.

As for the current exhibit, Michael Bise

savaged it in

...might be good. He wrote, "What it does offer is a great deal of justification for artworks that, while not egregiously awful, seem a long way from meriting serious consideration in a museum exhibition." I can see his point, but that didn't keep me from enjoying some of the pieces. In other words, why should I care if something is museum-worthy if I like it? But his next sentence was this--"More than a few artists in the show take on projects of artists before them and find themselves outmatched." This does speak to the provincial quality of the work. It's just very hard to be original.

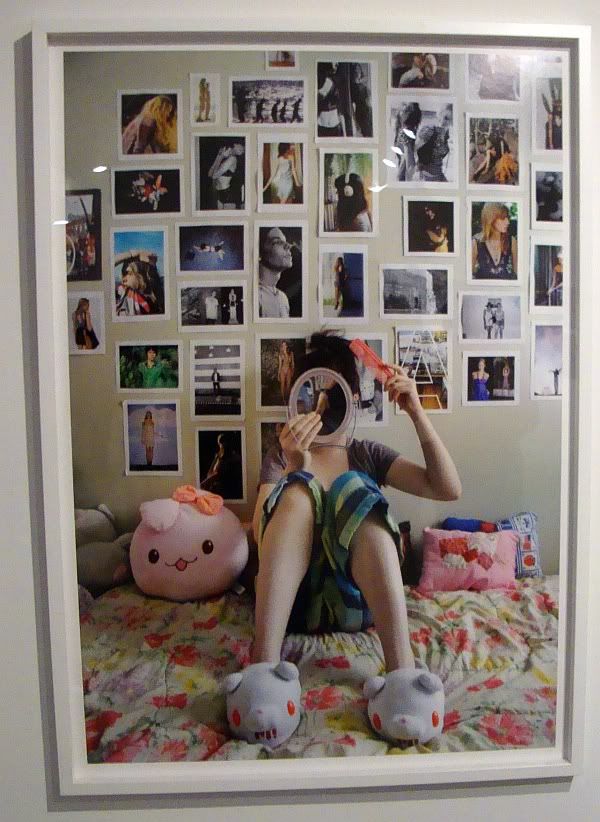

Santiago Forero, Hammer--Self Portrait, The Olympic Games Series, archival inkjet print, 2010 (from New Art in Austin 2011)

Santiago Forero, Hammer--Self Portrait, The Olympic Games Series, archival inkjet print, 2010 (from New Art in Austin 2011)

That said, I enjoyed some of the pieces. I had seen

Santiago Forero's work

at the Station Museum, where one of his photo self-portraits showed himself as a soldier. The three here depicted him participating in classic Olympic sports. The catalog text claims a lot for these photos, more than they can really sustain. But they have an uncomfortable power. Forero is a dwarf. To create these photos, he trained to be in top physical condition and had clothing appropriate for each sport custom made. But Forero

can't be an Olympic athlete, any more than he can join the U.S. Army (minimum height requirement, 58 inches). So these photos are fantasies, and could be seen as bitter reflections on the worlds that are closed off to dwarfs. But at the same time, they look

really cool. Forero really pulls it off--everything looks

perfect, better than a real photo of an Olympic athlete would look.The expression of total seriousness on his face is completely convincing. And this just adds an additional layer to the viewer's discomfort. Here is a dwarf, dressed up to

amuse us.

Ian Ingram, Our Koruna Muse, charcoal, pastel, encaustic, silver leaf and butterflies, 2009 (from New Art in Austin 2011)

Ian Ingram, Our Koruna Muse, charcoal, pastel, encaustic, silver leaf and butterflies, 2009 (from New Art in Austin 2011)

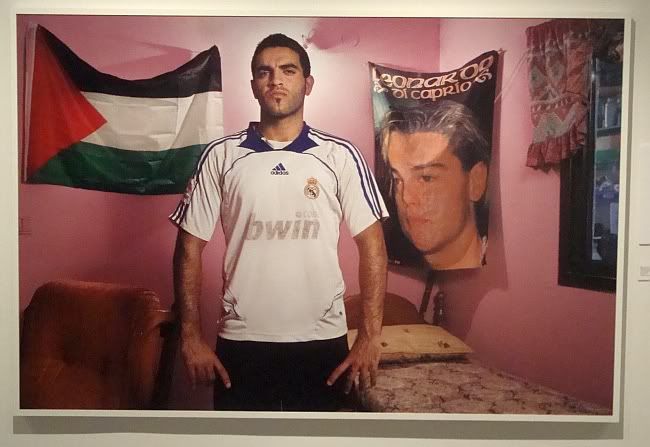

In terms of sheer bravura skill,

Ian Ingram's hyper-detailed portraits are completely amazing. But he's not attempting photo-realism. At least, that is only a side-effect of his ambition. On the contrary, he wants his work to be expressive. He attaches three dimensional objects to his paintings--butterflies, cloth, beads. These objects are real and layered on top of a realistic-but-constructed image. If this distinction is not important to Ingram, then why bother painting at all? Why not just take large-scale photographs? I think for Ingram, the end result is not the critically important thing--the process is. Now this is kind of a weird thing to say of a hyper-realist painter. For most of painting's history, what mattered was the image one ended up with. No one looking at, say,

The Oath of the Horatii, would think that the main thing about this painting was the process--the work, mental and physical, that David did. (No one with the possible exception of David himself.) Thomas McEvilley would explain this as a separation of art and life--specifically,

he would look to the way Kant divided aesthetics, ethics and cognition into distinct categories. McEvilley has written that this distinction began to break down with

the action painters--where the process was right on the surface--and then with performance artists, who fused art and life. I think for many artists throughout history, the intense concentration of making a painting or sculpture was therapeutic (long before that word gained currency) and meditative. For artists, at least, art and life are not separated. I think this is the case for Ingram--despite the fact he is toying with hyper-realism, what is important in these paintings is the intense process behind them.

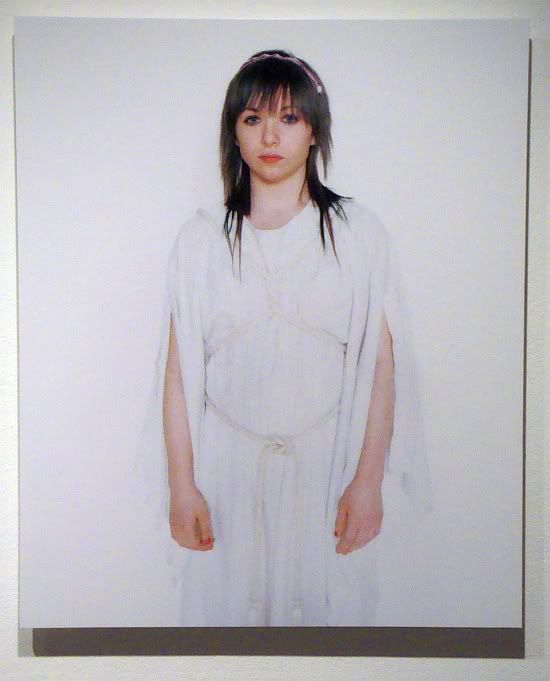

Debra Broz, Feeding, found ceramic objects, epoxy compounds, paint and sealer on a painted wooden stand, 2010 (from New Art in Austin 2011)

[Parallel]

Debra Broz, Feeding, found ceramic objects, epoxy compounds, paint and sealer on a painted wooden stand, 2010 (from New Art in Austin 2011)

[Parallel] by

Jesus Benavente and

Jennifer Reminchik strikes me as a prime example of work that "take[s] on projects of artists before them and find[s itself] outmatched," as Michael Bise complained. This performance,

in which each artist takes turns being a servant for the other artist, seems unsubtle, rehashed, and altogether lacking in fun. Another artist whose work is likely to remind one of earlier, bolder work by other artists is

Debra Broz. This is also work where you might think--does it really belong in a museum? But in another context, it would have been fine. I think these chimeras are amusing and well-made. As works of art, they are slight but pleasing. And the craftsmanship is top-notch.

Nathan Green's work has been growing on me. I don't love it, but I'm starting to like it. I reviewed works of his in a show last year at

Art Palace, and

what I wrote then still applies. Green has a solo show opening at Art Palace this week, and I may use it to try to make a more involved evaluation of his brightly colored, highly-patterned painting/installations.

There is something inherently problematic about an exhibit like this. A Nathan Green solo exhibit, for example, has a strong unifying factor--all the work is by one artist. And if a curator is building a show from scratch, she may have a concept of a visual conceit or a subject that unifies the show. The excellent show at the Blanton,

Recovering Beauty, is a good example. The artists in it were all veterans of a particular art space in Buenos Aires in the 90s, but even more important, they formed their own

school. The linking concept behind their work (yes to beauty, no to conceptual sterility and expressionist angst) was really strongly reflected in the work itself. But you can't have a unifying concept like that in

New Art from Austin. It has to be what the curators think is the best work being done in Austin by emerging artists, whether or not their work has any relationship with one another's work or not. Such shows are necessarily hodge-podges. There are several artists here whose work would be much better as a solo show in a gallery or an art space. Maybe this was what Bise meant when he wrote "seem[s] a long way from meriting serious consideration in a museum exhibition."