With a city as large and diverse and bustling with artistic activity as Houston, it’s easy to stumble upon great work. So as anyone can imagine, it was not difficult for me to come up with a top ten list for 2013. To be totally fair, however, I didn’t start writing for The Great God Pan is Dead until June of this year—which doesn’t mean much except that I was probably paying more critical attention in the second half of the year than the first. Therefore, it’s possible that I may be biased toward the latter half of 2013. At any rate, the following are my top ten pieces exhibited in Houston last year.

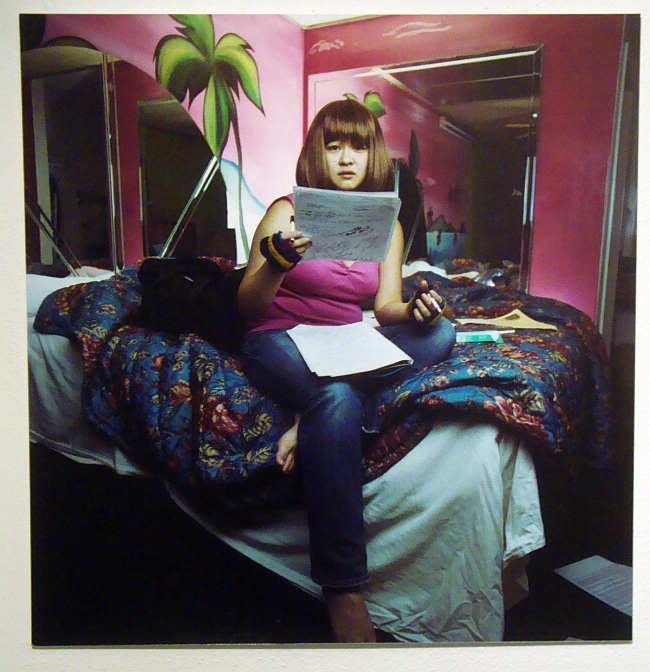

10. Bryan Forrester, Imogene (2012), The Big Show at Lawndale Art Center

Imogene didn’t even hit #1 on my Big Show top five list, so it may be surprising to see it crop up here, in the top ten of everything. But sometimes images stay with a person in unpredictable ways, and this nude, vomiting, tattoo-laden man stuck with me. Vile and rich, Forrester’s photography is lush and personal, and Imogene feels equally fearsome and romantic.

Bryan Forrester, Imogene, 2012, C-print, 24 x 36 inches (courtesy Lawndale Art Center)

9. Katrina Moorhead, Trying to describe the way that space wraps itself around an object (2013), The Bird That Never Landscape at Inman Gallery

Like a free-wheeling toddler, or perhaps the elderly homeless man with a pink tutu that frequents the Heights bike path, Katrina Moorhead’s work harbors an irreverent autonomy, seemingly unphased by its presence within a laser clean contemporary gallery like Inman. Yet strangely enough, it’s as if the work also depends on it being shown there, as if it requires that very platform to appear as autonomous. It is a bizarre and exciting paradox, and in Moorhead’s most recent solo exhibition, Trying to describe the way that space wraps itself around an object does not disappoint. A skeletal, black glittering bottle rack that looks like it came from a goth version of Claire’s, Trying to describe the way that space wraps itself around an object is strikingly, disturbingly, and simultaneously playful and menacing.

Katrina Moorhead, Trying to describe the way that space wraps itself around an object, 2013, antique bottle rack, powder coating, plasticine, bandage, 20”x19”x20” (courtesy Inman Gallery)

8. Geoff Hippenstiel, Untitled (2012), Winter Garden at Devin Borden

I saw Hippenstiel’s solo show Territorial Pissings at Devin Borden in early 2013. While they were nice and engaging enough, there was something almost absurdly commanding about his Untitled shown this past December in the group show Winter Garden. Following his modus operandi of extremely thick, smudgy brush strokes, here Hippenstiel employs sickly decadent silvers, pinks, and golds melding together, toppling each other. Despite its confinement to the wall, Untitled ensnares the viewer, somehow making her feel as though she’s trudging through sugary magma.

Geoff Hippenstiel, Untitled, 2012, Oil on canvas, 36” x 48" (courtesy Devin Borden Gallery)

7. Jillian Conrad, Bonsai Radio #1 (2013), Ley Lines at Devin Borden

When I reviewed Ley Lines earlier in the year, I wrote quite a bit about Conrad’s proclivities for drawing sculpturally, for crafting lines that reside in an anxious place between forming linkages elsewhere and existing as its own object. It’s this uncertainty that makes the work so compelling, and Bonsai Radio #1 is the best example of that liminality. A quiet work, Bonsai Radio #1 feels like it is whispering vital and indecipherable information.

Jillian Conrad, Bonsai Radio #1, 2013, Concrete, brass, rubber, 18”x20”12”

6. Romana Schmalisch, Notation of Efficiency (2013), From Here to Afternoon at the Glassell School

From Here to Afternoon was a cerebral show that required lots of time and attention from the viewer. Schmalisch’s Notation of Efficiency was one such work—but with an enormous payoff. A dry and intentionally tedious slide show of Laban Lawrence diagrams from an old fashioned projector, she infused the work with subtle yet nevertheless effective humor. And by controlling the cadence of the slides demarcated by remotely audible clicks, she was able to manipulate the viewer in and out of a lull while asking fascinating questions about the conflation of movement, labor, and efficiency.

Romana Schmalisch, Notation of Efficiency, 2013, Slide projection and model (bamboo sphere)

5. Wols, Oui, Oui, Oui (1946-7), Wols: Retrospective at the Menil Collection

In a recent review I compared Wols’ Oui, Oui, Oui to spelunking into a cave. What makes this painting so enrapturing is not only Wols’ ability to fervently convey a deeply interior language, but also his scrawling attempt to link the work back to an exterior world.

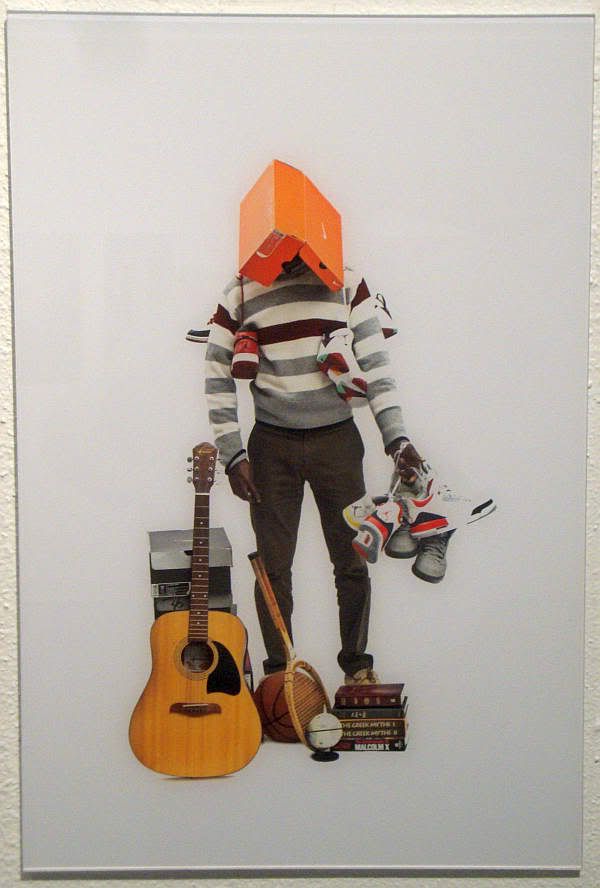

4. Jamal Cyrus, Texas Fried Tenor (2012), Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art at CAMH

I didn’t see the actual performance; instead I saw the remnants in the Valerie Cassel Oliver curated Radical Presence. And quite honestly, I don’t care about the performance and would even go as far to say that it doesn’t need it. A fried saxophone, it is voluptuous and grotesque, indicative and inviting of performative elements from the artist and viewer alike. It invokes scathing sensations of crunching and the taste of bitter metal while debilitating one form of expression to create another. And without a hint of didacticism, it poignantly and very tangibly lets the viewer in on the beautifully varied and layered complexities of blackness.

Jamal Cyrus, Texas Fried Tenor, 2012, Fried saxophone, taken from www.studiomuseum.org

Jamal Cyrus, Texas Fried Tenor, November 29, 2012, performance

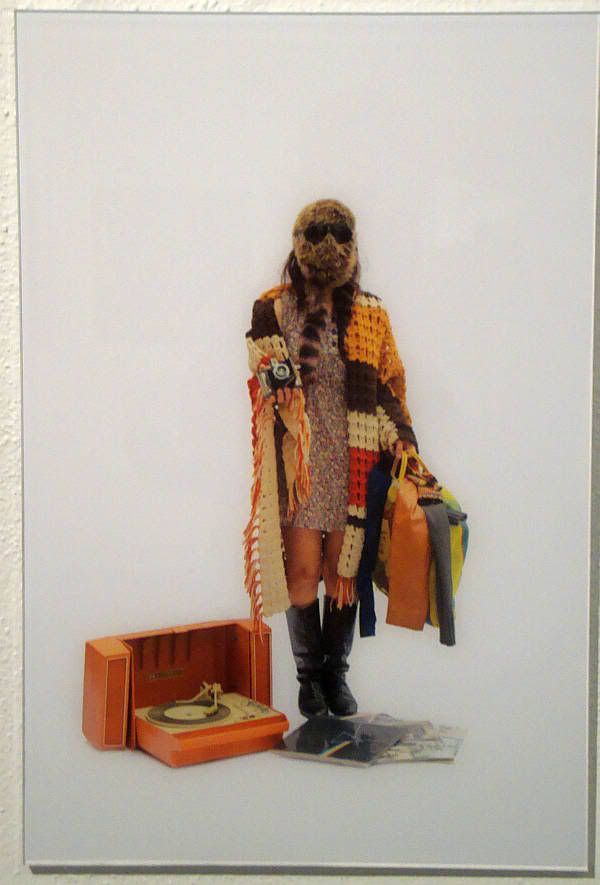

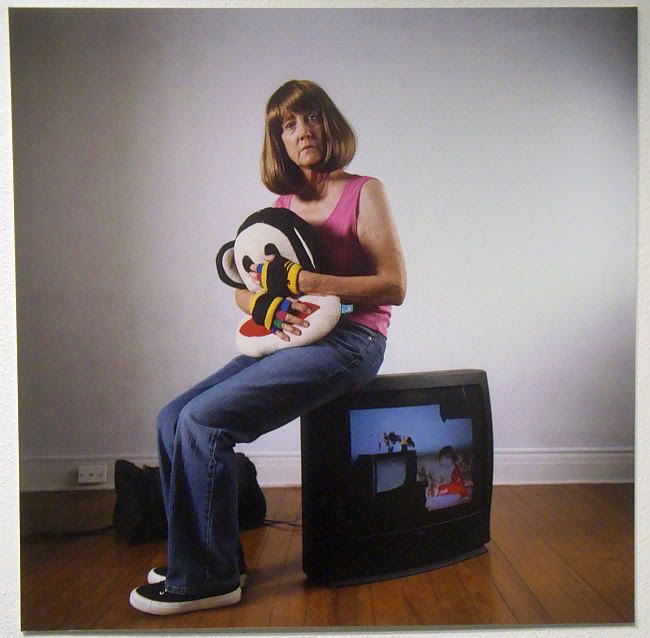

3. Joan Jonas, Good Night Good Morning (1976), Parallel Practices: Joan Jonas & Gina Pane at CAMH

Jonas is a pioneer of feminine performance and video art, and Good Night Good Morning is a seminal work from the art historical canon. A largely conceptual work, at the CAMH it was exhibited as an elderly video piece emanating from an outdated TV set—yet it still felt contemporary for both intentional reasons and not. While using repetition in all art, not to mention conceptual works, is thoroughly tread and fully utilized territory, it still feels fresh here: one can pick up on miniscule though revealing nuances as Jonas consistently greets the camera each morning and night. Also, due to glitches in the then-new technology, the camera created faded double images as Jonas would traverse the room. A happy accident, the work is fraught with ghost images of Jonas haunting herself.

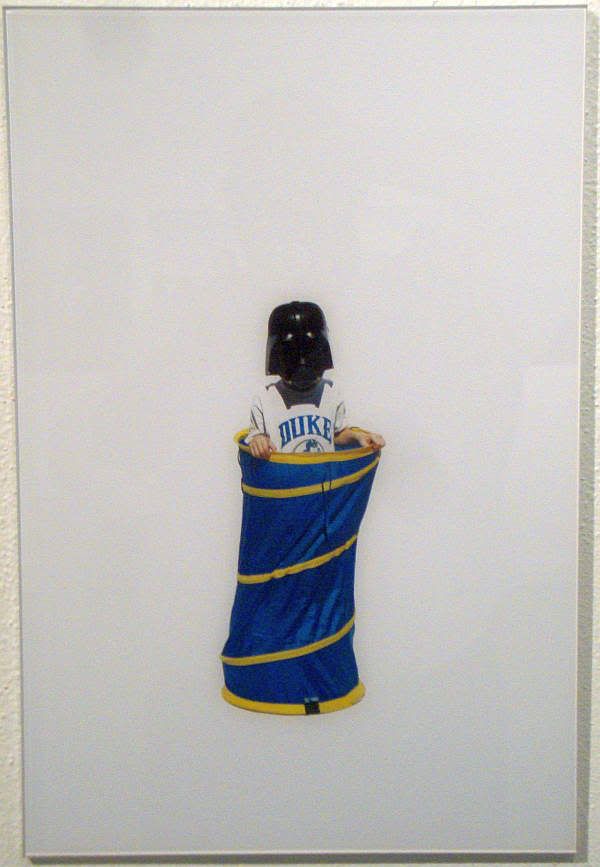

2. Leslie Hewitt and Bradford Young, Untitled (Structures) (2012) at the Menil Collection

Speaking of hauntings, Untitled (Structures) is a cinematic recounting of present day architecture that inhabited various critical moments within the civil rights movement. Long time collaborators Hewitt and Young formally captured the innards of these spaces with barely detectable movement, providing mere glimpses or suggestions of history. These lush cinematic shots fuel an air of mystery, leaving the viewer craving more information, with no choice but to fill in the blanks herself.

Leslie Hewitt and Bradford Young, Untitled (Structures), 2012, Dual channel video

1. Soo Sunny Park, Unwoven Light (2013) at Rice Gallery

No one can argue against Unwoven Light’s airy and dynamic pulchritude. A weaving structure filling the installation space at Rice Gallery, Unwoven Light contains thousands of lightly tinted acrylic panels continually refracting light, constantly changing color throughout the day. But the real game changer for me was its unexpected commanding, and really demanding, movement from the viewer. Using tons of winding chain link fence, Park builds an armature that in some places hugs the viewer in like a vortex while spewing him out in others.

So Sunny Park, Unwoven Light, 2013, Chain-link fence, Plexiglas, acrylic film, dimensions variable