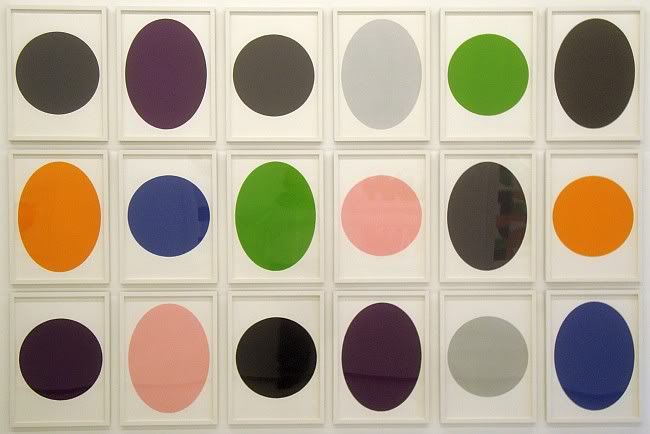

Kyle Young, Infinite Reduction Series, monotypes, 72" x 110", 2012

Infinite Reduction Series by Kyle Young at Art Palace is the key to all the other pieces in the show. The work, both monotypes and paintings, involve cutting up and reassembling circles and ellipses and collaging the results together.

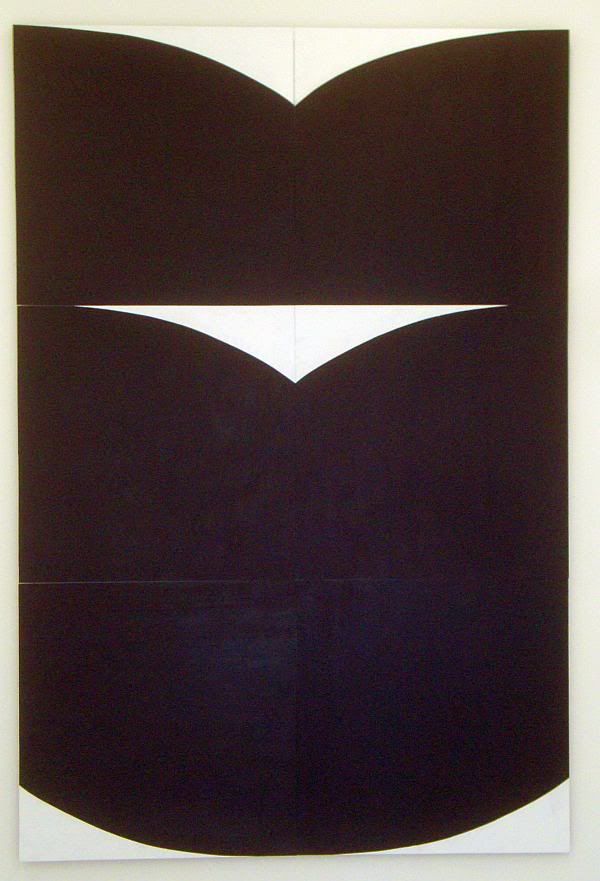

Kyle Young, Chalice Reversed, acrylic on panels, 116" x 77", 2011

Kyle Young, In Search of Human Contact, monotype collage, 32" x 20", 2012

Kyle Young, from left to right, Portrait in Orange and Purple, Portrait in Pink and Gray, Portrait in Green and Orange, monotype collages, 21 1/2" x 14 1/2" each, 2012

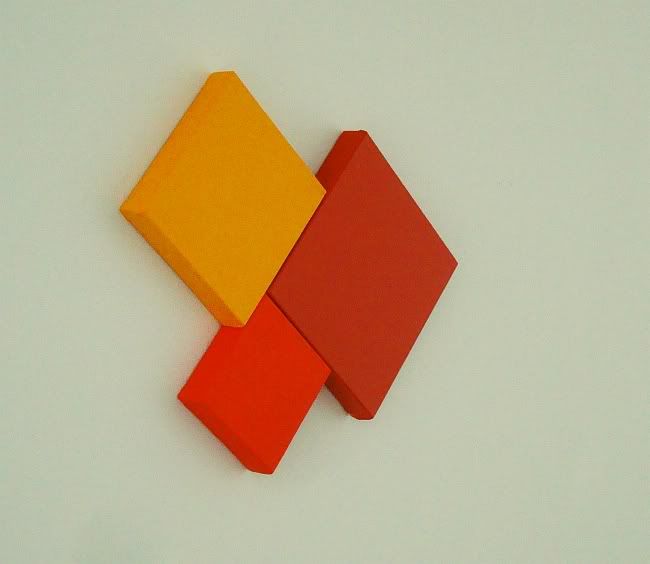

My first reaction to these was that they reminded me of Ellsworth Kelly--bold geometric forms, simple color schemes (only two or three colors), very flat colors (not sign of brushstrokes in the paintings). But the way he assembles his pieces might also remind a viewer of Robert Mangold. What this says to me is that whatever else he is doing, Kyle Young is in a dialogue with early minimal painters. This dialogue is not oedipal. There is no obvious anxiety of influence. He seems to respect his forefathers and is willing to work in the vocabulary that they created.

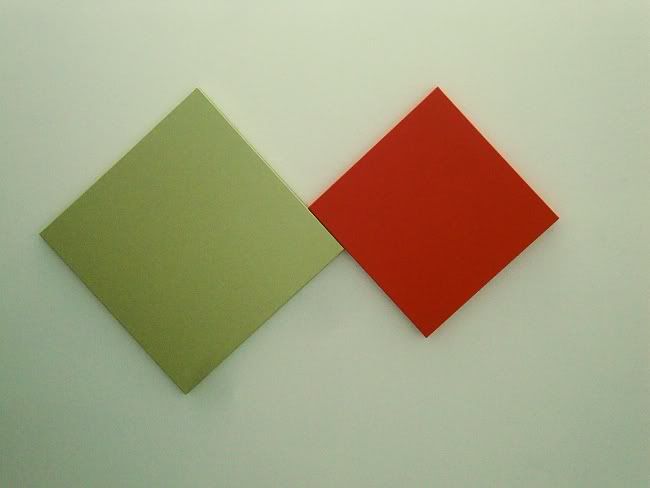

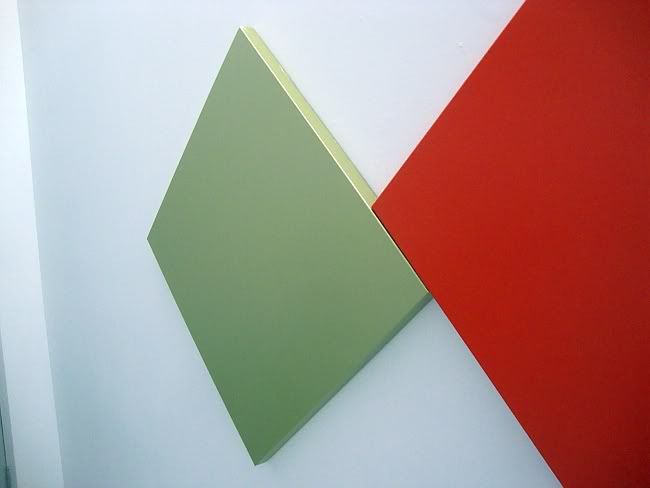

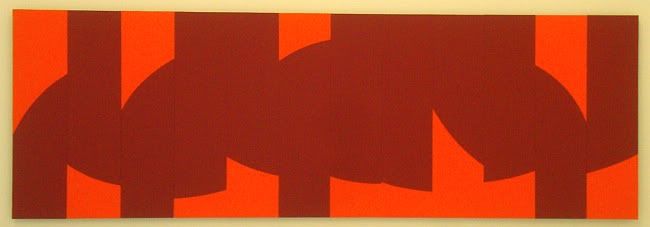

Kyle Young, Dialogue--Red & Orange, acrylic on panels, 40" x 121 1/4", 2012

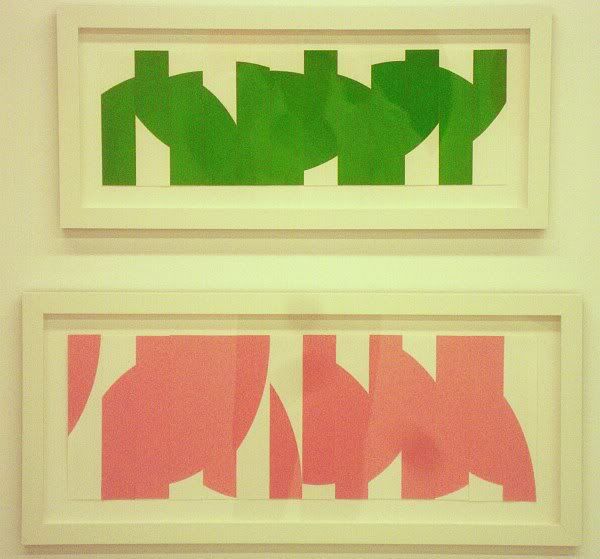

Kyle Young, top Dialogue--Green, monotype collage, 8" x 24", 2011; bottom Thank You, Robert--Pink, monotype collage, 8" x 28", 2011

In these pieces called Dialogues, I think the title refers to the dialogue between the two colors. The collage is arranged so that it almost looks like typography--like a sign. But it could also be the dialogue I mentioned above. And the piece Thank You, Robert--Green might refer to any Robert, but it could be Robert Mangold he's thanking, couldn't it?

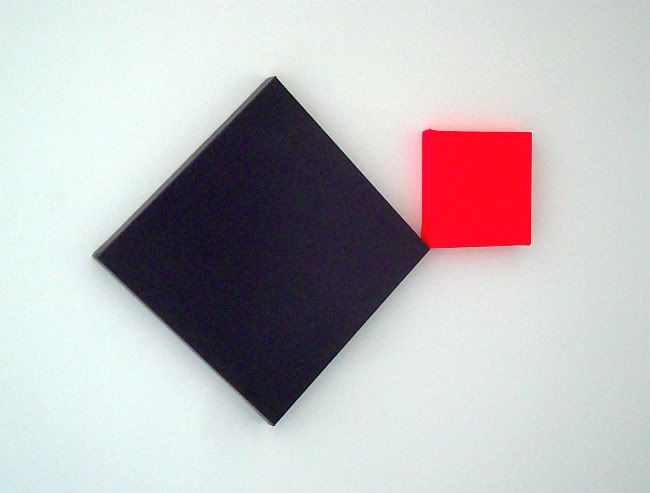

Kyle Young, Fathers, acrylic on panels, 88" x 80", 2011

Kyle Young, In Honor of Our Fathers II, monotype collage, 17 1/2" x 16", 2011

I don't mean to suggest that this exhibit is all about Young's relationship with his minimalist daddies, but with pieces like these, it's not a totally crazy conclusion. But the fathers in Fathers and In Honor of Our Fathers II could be a reference to the circles and ellipses that were sliced up and reassembled to create these collages. In fact, the fact that the word "fathers" is plural might refer to the fact that in each, two circles were sliced up, one black and one red (in the painting) or orange (in the monotype collage). But there are other possible fathers that Young could be referencing, including artistic forefathers.

The pieces are lovely to look at. They encourage a viewer to mentally unassemble them to figure out how Young took apart their source circles and ellipses. And the more art historical viewer might look at this show in relation to such "fathers" as Kelly and Mangold.