Sculpture in inconvenient. It takes up a lot of space and it therefore difficult to collect. There is a funny quote that is variously attributed to Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt: “Sculpture is something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting.” As far as I know, Reinhardt never made sculptures, but Newman did. You can see one of his, Broken Obelisk, in Houston in front of the Rothko Chapel. (And at the University of Washington, at Storm King and at the Museum of Modern Art.)

Admittedly, sculpture can be almost anything now, an idea put forth in the classic essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” by Rosalind Krauss, 1979. The anythingness of sculpture was pushed even further in Thomas McEvilley’s book, Sculpture in the Age of Doubt.

Since 2016, every other year (except 2020) has had a “Sculpture Month” here in Houston featuring a month of sculpture exhibitions at multiple venues across Houston. I want to speak briefly about two of the venues and the sculpture within them. One is a venue I mentioned earlier this week where Nestor Topchy did his performance—The Silos. Topchy’s performance was part of Sculpture Month (going with the almost infinitely malleable definition of sculpture). The rest of the silos were also used for a variety of site-specific sculptures.

The first one I came across after entering the space was by Shawn Smith called UnNatural Influence, made of plywood, ink, acrylic paint and silk flowers.

It is a classically Texas subject, a bucking bull, but made out of blocks of wood that imitates pixels. In some ways, this feels like a very traditional sculpture—a single, free-standing object meant to look like a specific thing. Praxiteles would recognize this sculpture, except maybe for the pixelation effect. He would have been most amazed by the artificial lighting effect, which combined with the cave-like interior of the Silos provides a dramatic shadow.

That shadow makes me think of neolithic hunters sitting around a fire in a cave, recounting their hunt for the wild auroch. Aurochs were wild cattle in Europe and Asia that went extinct around 1650. There are depictions of them in cave paintings, including four painted on the walls of the caves at Altamira in Spain. And Altamira is the name of this exhibit, perhaps in honor of cave-like interiors at the Silos.

Susan Budge made an installation that made use of the entire silo she had. Stardust features a central object, surrounded by other objects. There is a small floor-level hole in the wall of the silo, into which Budge has placed several ceramic objects and lighted with a warm, incandescent light—in contrast to the dark, bluish light for the rest of the silo. It makes me think of a campfire. Above the central object are star-shaped ceramic figures.

I took them as representing actual stars. In the center of the ceiling of the silo is a large ceramic eye, seemingly gazing down on the scene below. If the theme of the exhibit as a whole is based around our primal need to create as represented by the paintings on the cave wall at Altamira, then what Budge has created perhaps is a depiction of hunter-gatherer types sitting around a campfire with a totem under the stars.

The largest piece was by Kathryn Kelley. Kelley is an artist I’ve written about frequently in the past. Her work always combined a fierce physicality and emotionality and an intellectual underpinning. This probably helps explain why she moved away from the Houston area to get a PhD in studio art. Since she moved, I haven’t seen any new work from her locally, which made me sad. But she’s back for Sculpture Month. This three-part installation is called Disproportionate Dream Fragments, and visually doesn’t seem all that distinct from her earlier work. Instead of using cut-up inner tubes as material, she has found new, grungy recycled material to work with. I always worry that I might catch tetanus from just looking at Kelley’s sculpture.

The rusty bedsprings, the loose nails, all adds up to a somewhat dangerous installation. I know that there are artists who have approached this level of pure grunge, especially assemblagists like Robert Raushenberg, Wallace Berman, Ed Kienholz, and George Herms (some of my favorite artists). And yet, none of those artists has ever given me a feeling of physical menace like Kelley does.

That chair could kill you.

What these photographs utterly fail to convey is the clautrophobic sensation of being in these silos with the work. Kelley didn’t make it easy to breeeze through—you kind of have to squeeze past stuff to see everything. And I hardly need to say that photographing all the work in a given silo is next to impossible.

The installation seems to represent a homey, domestic interior made from scratch by a troglodytic family who only knew about things like beds, chairs, and wardrobes from television images. Their cargo cultic approximations of “home” are dangerous to use and not terribly functional.

Having said this, I suspect that Kelley has a well-thought-out reason for everything, amply backed by theory and with a highly personal underpinning. This has frequently been the case with her earlier artwork. Kelley keeps a blog, but for the past few years, most of her posts have been about why an artist should write. It feels like a very solopsistic project, an artist writing about artists writing. Lots of quotations and excerpts. Her writing is dense and poetic. I was hoping there might be some clues about Disproportionate Dream Fragments there, but I didn’t see any—nothing obvious, anyway.

The other Sculpture Month show I wanted to touch on was also a group show held at the house of sculptor Michael Sean Kirby. I like house galleries and apartment galleries. I couldn’t imagine doing it myself—my tiny apartment is too cluttered. But Kirby’s house is kind of perfect for this, presumbly because he, unlike me, is capable of keeping it tidy. The show in his house was called “After Altamira” and featured six artists. I’m going to mention two, partly because of all the photos I took that night, they had the only ones that came out good. I do want ot give a shout-out to Ronald L. Jones’ unphotographable installation, Cavity. His work, mostly made of webs of yarn stretched over a space, is extremely difficult to photograph.

Kamila Szczesna is a Galveston artist who often works with spherical shapes wrapped in stretchy materials. But for this exhibit, the spheres came out of their wrappings. The piece above, interwoven, is made of mouth blown glass and hair. The glass spheres look so delicate, like soap bubbles.

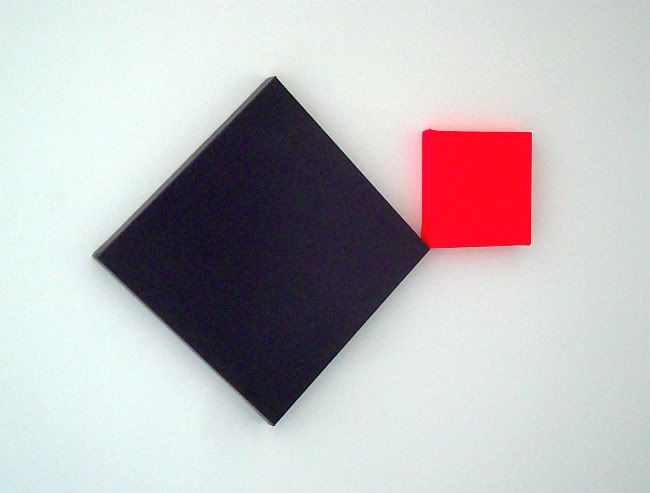

Patrick Renner is an artist I’ve followed for years, writing about his work on my blog and for other publications. His work is closer to the assemblagists I mentioned above than Kathryn Kelly art is—one can certainly see a little George Herms in introvert above. With Renner’s assemblage work, the component parts often have a personal meaning. In this case, they include “the only remaining side of a trick music box my paternal grandfather made when I was a kid” and a “bat house that used to be on my parents’ house.”

The spookiest detail was this tiny bat skeleton encased in acrylic.