Today's report is on I, Rene Tardi, Prisoner of War at Stalag IIB Vol. 3: After the War, the third volume of Jacques Tardi's biography of his father as a soldier and prisoner in World War II. I've reviewed volume 1 and volume 2 earlier on this blog. Here is everything I've written about Jacques Tardi on this blog.

Showing posts with label Jacques Tardi. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jacques Tardi. Show all posts

Monday, November 23, 2020

Robert Boyd's Book Report: I, René Tardi, Prisoner of War in Stalag IIB: After the War

Labels:

Jacques Tardi

Tuesday, July 23, 2019

I, René Tardi, Prisoner Of War In Stalag IIB Vol. 2: My Return Home by Jacques Tardi

Robert Boyd

I, René Tardi, Prisoner Of War In Stalag IIB Vol. 2: My Return Home by Jacques Tardi (Fantagraphics Books, 2019)

by Jacques Tardi (Fantagraphics Books, 2019)

This volume is a little more expository than the first volume. As the Russians advanced from the east, René Tardi's stalag was emptied out. He and the other prisoners were marched by their captors to the West, staying out of the hands of the Russians, British and Americans. Jacques Tardi got his father to write a narrative of his imprisonment and gradual liberation some 40 years after the fact, and then researched the route to try to figure out what his father actually did. Like so many displaced persons at the end of the war, the way home was not a straight path. (In this, My Return Home resembles Primo Levi's classic memoir of his liberation from Auschwitz, known variously as The Truce or The Reawakening

or The Reawakening .)

.)

Unlike the first volume, Jacques feels the need to keep us readers informed about what is happening in the last days of the war. René Tardi's group of POWs managed to skirt some of the major events at the end of the war, witnessing occasional aerial battles but avoiding heavy allied bombardments. But while they are slogging through the cold, scrambling to find whatever food they might, we are given a disjointed account of the last days for World War II. It feels overly expository, but it serves the purpose of reminding us readers of how little the vast hordes of wandering displaced persons and foot soldiers knew of what was actually happening all around them.

The book begins almost uniformly monochromatic--black and various shades of greenish grey, but as René gets closer to France, little splashes of color start to appear. In particular the red and blue of flags and red-crosses, which seem to symbolize liberation. Eventually fleshtones return and when René is reunited with his wife Henriette, Tardi allows himself a brilliant pink panel filled with flowers.

I want to make a note about the translation. Earlier volumes of Tardi that were published by Fantagraphics were translated by co-publisher Kim Thompson. Thompson passed away a few years ago, which suggested that maybe the Tardi volumes would stop (given that Thompson was their great champion). But thankfully they haven't and the translation is by Jenna Allen. Even though Thompson was fluent in French, I like Allen's translations better. I can't judge their faithfulness, since I can't read French. But a lot of Tardi's characters (including René Tardi) are tough guys, and Thompson's "tough guy" voice never felt authentic. But Allen pulls it off better than Thompson. (It pains me to say so because I loved the man...)

I, René Tardi, Prisoner Of War In Stalag IIB Vol. 2: My Return Home

This volume is a little more expository than the first volume. As the Russians advanced from the east, René Tardi's stalag was emptied out. He and the other prisoners were marched by their captors to the West, staying out of the hands of the Russians, British and Americans. Jacques Tardi got his father to write a narrative of his imprisonment and gradual liberation some 40 years after the fact, and then researched the route to try to figure out what his father actually did. Like so many displaced persons at the end of the war, the way home was not a straight path. (In this, My Return Home resembles Primo Levi's classic memoir of his liberation from Auschwitz, known variously as The Truce

Unlike the first volume, Jacques feels the need to keep us readers informed about what is happening in the last days of the war. René Tardi's group of POWs managed to skirt some of the major events at the end of the war, witnessing occasional aerial battles but avoiding heavy allied bombardments. But while they are slogging through the cold, scrambling to find whatever food they might, we are given a disjointed account of the last days for World War II. It feels overly expository, but it serves the purpose of reminding us readers of how little the vast hordes of wandering displaced persons and foot soldiers knew of what was actually happening all around them.

The book begins almost uniformly monochromatic--black and various shades of greenish grey, but as René gets closer to France, little splashes of color start to appear. In particular the red and blue of flags and red-crosses, which seem to symbolize liberation. Eventually fleshtones return and when René is reunited with his wife Henriette, Tardi allows himself a brilliant pink panel filled with flowers.

I want to make a note about the translation. Earlier volumes of Tardi that were published by Fantagraphics were translated by co-publisher Kim Thompson. Thompson passed away a few years ago, which suggested that maybe the Tardi volumes would stop (given that Thompson was their great champion). But thankfully they haven't and the translation is by Jenna Allen. Even though Thompson was fluent in French, I like Allen's translations better. I can't judge their faithfulness, since I can't read French. But a lot of Tardi's characters (including René Tardi) are tough guys, and Thompson's "tough guy" voice never felt authentic. But Allen pulls it off better than Thompson. (It pains me to say so because I loved the man...)

Labels:

Jacques Tardi

Friday, July 30, 2010

More Recently Read Comics

Birchfield Close by Jon McNaught

This tiny book is a designer's notion of a good comic. It contains a variety of suburban vignettes, all of which appear as if you are an observer standing some distance away from them, quietly observing them and taking note. They don't cohere into a story or even have much relationship to one another. You see part of some television show. You see a cyclist fall off his bike and pick himself up. You see the aerial ballet of a large flock of birds. It's all rather impersonal, and the art reflects that. It's a lovely, gemlike piece of work.

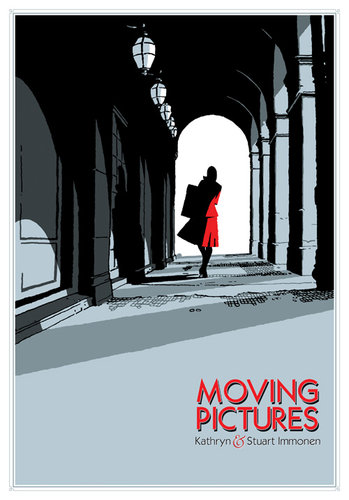

Moving Pictures, written by Kathryn Immonen and drawn by Stuart Immonen

Set in an interesting milieu (the Louvre during World War II), this book is doomed by its pointlessly oblique storytelling, its terrible dialogue, and its characterless art. Apparently Stuart Immonen is a popular mainstream (i.e., super-hero) comics artist. I am unfamiliar with that work, but here he seems to be attempting a clear line style. His work resembles that of Paul Grist, but he lacks Grist's dynamism and humanity.

Weathercraft by Jim Woodring

One doesn't "review" a story like this. One genuflects before it. Mysterious as usual, we see what seems like a near redemption of that most human of creatures, Manhog.

Wally Gropius by Tim Hensley

Hensley has always been a talent to watch. Prior to this book, the coolest thing I had from him was a soundtrack he recorded for Dan Clowes' Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron. This book takes a lot from Clowes. Like Clowes, Hensley has an interest in the minimalist anonymous comics for small children from the 1960s and 70s. Wally Gropius is not merely a pastiche of them. I hesitate to say it is a deconstruction, because that implies a certain logical approach. Instead, Wally Gropius reads like an attempt by an alien civilization to communicate with us, having only read these comics prior to the attempt. Meaning is struggling to come to the surface of this sea of signs.

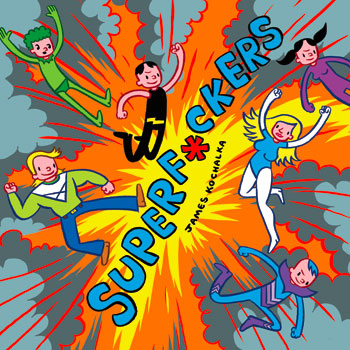

Superf*ckers by James Kochalka

Superf*ckers is a seriously funny idea, and it works for a good chunk of this book. It starts to run out of steam in the end, though. The superhero team here are a bunch of hard-partying teenagers. Instead of incomprehensible teenage super teams like the New Mutants or the Teen Titans, this team acts more like the cast of a reality show. And that's really funny. Kochalka's intensely colored art here is really pleasing as well.

Wilson by Dan Clowes

Really deserves a long, analytic review. Suffice it to say here that Wilson is really good--a story of a deeply unpleasant misanthrope told in a visually interesting and formally inventive way. It's good to see Clowes not working on mediocre movies and instead doing really great comics--the thing he was born to do.

It Was the War of the Trenches by Jacques Tardi

Another book that deserves a long, detailed review. It's a great one that you must own if you are serious about comics as art. One thing that struck me is how indebted Tardi is to Louis Ferdinand Celine. Celine's cynical "fuck it" attitude permeates French cultural production, and It Was the War of the Trenches is no exception. In this series of short stories, the luckless protagonists seem to be asking, over and over again, "Can you believe how fucked up this is?"

Thursday, June 3, 2010

Great Comic Art at the Latest Artcurial Auction

Here in the U.S., the big auction house for comics art is Heritage Auctions (in Dallas of all places). They run their auctions primarily but not exclusively online--it is really easy to bid with them.

I wish French auction house Artcurial made it as easy. Their website is in French and English, which implies to me that they want an international clientele. But the way they do internet bidding is really weird and confusing to me, not practical and easy the way Heritage does.

Still, they have really nice auctions with huge amounts of interesting comics art, mostly Franco-Belgian, but including some great pieces from around the world. The next Artcurial comics auction takes place June 5, so if you find yourself in Paris, stop by and bid on a few lots! Here are some of the things I would be bidding on if I were there...

Soirs de Paris cover by Avril

A page from Aguirre by Alberto Breccia

A page from Leon La Came by Nicolas de Crecy

An illustration by Jacques Tardi for Death on the Installment Plan

I wish French auction house Artcurial made it as easy. Their website is in French and English, which implies to me that they want an international clientele. But the way they do internet bidding is really weird and confusing to me, not practical and easy the way Heritage does.

Still, they have really nice auctions with huge amounts of interesting comics art, mostly Franco-Belgian, but including some great pieces from around the world. The next Artcurial comics auction takes place June 5, so if you find yourself in Paris, stop by and bid on a few lots! Here are some of the things I would be bidding on if I were there...

Soirs de Paris cover by Avril

A page from Aguirre by Alberto Breccia

A page from Leon La Came by Nicolas de Crecy

An illustration by Jacques Tardi for Death on the Installment Plan

Labels:

Alberto Breccia,

auctions,

Avril,

comics,

Jacques Tardi,

Nicolas de Crecy

Thursday, December 24, 2009

The Best Comics of 2009

Robert Boyd

I was going to do the top 10 comics of 2009, but I just couldn't limit myself to 10. So here are my top 15. Some big caveats going in. First, there are comics that came out this year that look really good that I haven't read yet. (For example, the new Joe Sacco book.) There are also probably comics that came out this year that are really good that I just don't know about. And finally, this list is personal and idiosyncratic. It is the list of a guy who values art comics and alternative comics far more than mainstream comics. My tastes were formed in the 80s and 90s, and I think that shows. I am someone who loves the comic strip form, especially as practiced before World War II. Also, I have found over the past few years that I haven't been reading many comic books. So the only comic book on this list is Multiforce (and calling it a comic book is kind of a stretch).So with that in mind, here we go!

The Top 15

1) Asterios Polyp by David Mazzucchelli. See my review here. A beautiful, rigorously structured, funny and moving book.

2) You Are There by Jean-Claude Forest and Jacques Tardi. See my review here. This is, like so many things on my list, actually quite an old work. But this edition is the first published in English.

3) Jack Survives by Jack Moriarity. This powerful body of work was mostly published in RAW in the 80s. Moriarty approaches these comics as a life-long painter, and this edition reproduces them as paintings, not as high-contrast line drawings, which is how they were originally printed. The result is mesmerizing without detracting from the stories. The stories are kind of abstractions of early 50s manhood. A guy in a hat with his family and his house... Brilliant pieces of minimalism created with a neo-expressionist painter's brush.

4) The Book of Genesis Illustrated by Robert Crumb. Awe-inspiring. In a way, Crumb has been too faithful. Using a very literal translation of the Bible by Robert Alter as his starting point, he tries to keep interpretation to a minimum. One result is that the comic form is compromised in at least one obvious way. The Bible will have passages that read, "He said, Blah blah blah" In the Bible, there are no freestanding quotations of spoken words. So in a panel where Crumb is depicting someone speakings, there is always a little caption preceeding the word balloon that says something like, "And then Jacob said" This is really weird. What these captions are saying is being shown through the use of the visual device of the word balloon. This was just one of the awkward things that comes from including every word of a prose work in a different medium (comics). Of course, his artistry makes up for a lot of awkwardness. You can stare at this book forever. One aspect of Genesis that is really boring is the listing of names--the "begats." But Crumb, drawing all these hundreds of faces, turns that weakness of the text into an overwhelming strength--each face, so individual, implies a story, a life. It's a beautiful piece of work.

5) George Sprott (1894-1975) by Seth. This ran in the New York Times Magazine, and for this book, Seth has added some incidental art (spectacular, of course--it includes cardboard models of the buildings from the story) and two short recollections of Sprott's boyhood and youth. Seth uses a technique that I think really works better for him than telling a story as a straight narrative. Each page is its own little episode--set in its own time, focusing on a particular person. The sum of these episodes is George Sprott's awful life--an asshole whose career is an extended riff on one minor achievement of his young manhood. It is amazing how compelling this nasty character is!

6) The Complete Little Orphan Annie, vol. 3 by Harold Gray. See my review here. An unusually powerful melodrama from the depths of the Depression.

7) Popeye, vol. 4 by E.C. Segar. This is the volume with the great "Plunder Island" sequence, which introduced many of us to the genius of Segar when it was reproduced in the Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics. But the whole of this book is top-notch, Segar at his greatest. Includes a lengthy and hilarious sequence of Popeye in drag, romancing a baddie.

8) Journey, vol 2 by William Messner-Loebs. An underappreciated classic from the 80s, published in the first great flush of "independent comics" that brought us classics like Love & Rockets and Yummy Fur. MacAlistaire and the failed poet Elmer Alyn Craft (who was introduced in the first volume) are stranded in the barely there settlement of New Hope for a winter. This village is claustrophobic and full of horrible secrets. Craft is obsessed with finding them--MacAlistaire is interested only insofar as it will help him survive the winter. Messner-Loebs' drawing has lost what little polish it exhibited in the first volume. It becomes ragged and urgent here, fitting the psychologically intense and unsettling story.

9) Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, vol. 8. This is a particularly rich volume. Gould made a decision to not send Dick Tracy to war, but the war pops up. Pruneface is an enemy agent that Tracy must shut down. His most terrifying villain in this volume, however, is Mrs. Pruneface, a hulking skullfaced woman seeking revenge for her man's death. And of Tracy's iconic villains, Flattop rounds out this volume (and we meet Vitamin Flintheart, who will be a recurring character). The art is, as always, excellent.

10) Multiforce by Mat Brinkman. I've read a lot of these strips here and there, and only now realize that they all sort of fit together.This oversized, saddle-stitched book brings the whole saga together. And "saga" is the right word. Multiforce is simultaneously the kind of epic a ten-year-old boy would conceive of and at the same time the kind of art that a sophisticated product of elite art education might create. The work slithers between these two poles trickily. And Brinkman never fails to be amusing. This may remind some people of Trondheim and Sfarr's Dungeon books, which are clever and funny, but frankly feel contrived next to Multiforce. Great, weird art and storytelling.

11) Cecil and Jordon in New York by Gabrielle Bell. Very good--Bell's art is outstanding in a non-showy, matter-of-fact way. In some stories, she never shows you someone's face in a close-up, and in some of her autobiographical stories, almost ever figure is drawn full-figure--in other words you see their feet and heads in every panel they are in. The distance from the observer and the characters is pretty large. It's a weird way to tell an autobiographical story--its as if the author was pretending not to know what was going through the mind of the character. It creates an interesting contradiction, as if Bell were alienated from her earlier self. That feeling carries through in her fiction stories too. The characters seem to feel disconnected from their lives, even as they have what (on the surface) seem like pretty engaging experiences. Her characters never get happy, which can be kind of a downer. The title story even features a character who would be happier as a chair--she'd feel useful that way, and not have to struggle the way she did when she was a full-time girl.

12) Everyone Is Stupid Except For Me by Peter Bagge. This collection has been a long time coming. Peter Bagge has been doing these reportorial strips for Reason for years, and before that he did similar strips for the late, lamented web magazine Suck. His reporting is infused with his own style of humor, which will resonate with fans of Hate (like me). But what is different is that he is actually reporting here--going out, covering events, talking to participants, doing research, etc. Satirical reporting may have been around forever, but in modern times, Spy was the first big practitioner of it. Spy spawned a host of mostly online followers--Suck, of course, and nowadays websites like Gawker and Wonkette. But those sites are mostly picking up news and adding their own snarky spin. Like the writers for Spy, Bagge is going out and doing the digging himself, and like the great magazine reporters of the '60s and '70s, he puts himself in the stories. Most of this work is in service of Bagge's (and Reason's) libertarian beliefs. Don't expect him to be "fair"--he has a point of view and he is going to hammer it home. But he is a humorist first, so he is constantly mocking his own side (if they are mockable) as well as the protagonists of his stories. But if you are not a libertarian, you'll find yourself muttering "That's outrageous!" at many of Bagge's broader caricatures of liberals or conservatives. Get past that! These strips are very, very funny, and if they force you to work harder to defend your point of view against Bagge's arguments, is that bad?

13) You’ll Never Know book 1: A Good and Decent Man by Carol Tyler. Great but somewhat confused biography/memoir. Carol Tyler is attempting to tell the story of her dad in World War II. She is faced with a problem, though. Tyler's dad doesn't want to talk about a certain part of it--his time in Italy. We are given hint that he saw a literal "river of blood," and the trauma has kept him silent for decades. Even his wife doesn't know. Tyler herself is going through her own stuff--an absent husband, a beautiful teenage daughter, life. Tyler is better at short pieces, where she can focus. This is a glorious mess, but a moving and beautiful one. The format is unusual too. Tyler uses the horizontal format of a scrapbook. Also, for some reason, the whole thing is not being told in one volume. I suppose I will wait long frustrating months (and years?) for the next volume.

14) Map of My Heart by John Porcellino. I think this could have been better edited. As it is, they just reprinted whole issues of King Kat, including letters to Porcellino. This approach, however, feels consistent with the basic vibe of King Cat. The stories are slight, filled with simple joy or being alive or with small regrets. In between the stories, there are journal entries and annotations where Porcellino tells us about the arc of his marriage, his sense of failure at getting divorced, his mysterious chronic illness. etc. These are almost never the subjects of his comics. At least not directly. His work is oblique that way, but never obscure. On the contrary, emotion is right on the surface. Lots of very moving stories here.

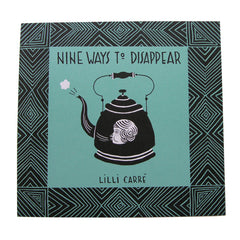

15) Nine Ways to Disappear by Lilly Carre. This is a collection of witty little stories. Some have the flavor of modern fairy tales ("The Pearl"), and all of them have an other-worldly quality. She uses a primitive panel progression--one panel per page, like the old woodcut guys (Lynd Ward, Franz Masereel). To emphasize the separateness of each panel, each one has a decorative border (recalling Lynda Barry, perhaps). But the stories flow perfectly well, and doing it this way made me linger a bit over each panel. Which is nice, because they are lovely. My favorite story is "Wide Eyes", the story of a man who falls in love with a woman with widely-spaced eyes, but feeling oppressed by them, finds he can hide from her by standing very close to her face, between her eyes and apparently outside her field of vision. My favorite character is the only recurring one, a lonely storm grate.

(A little side note--of the top 15 books, four were published by Fantagraphics, three by Drawn & Quarterly, three by IDW, and one each by Norton, Buenaventura Press, Pantheon, Little Otsu, and Picturebox.)

Honorable mention

Here are some other 2009 comics I liked.

The Best American Comics 2009 edited by Charles Burns

The Cartoon History of the Modern World vol. 2 by Larry Gonick

The Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, vol. 7

The Complete Little Orphan Annie, vol. 2 by Harold Gray

A Drifiting Life by Yoshiharu Tatsumi

Ho! by Ivan Brunetti

Humbug by Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Davis, Al Jaffee, Arnold Roth, Will Elder, etc.

Key Moments from the History of Comics by François Ayroles

Low Moon by Jason

Masterpiece Comics by R. Sikoryak

A Mess of Everything by Miss Lasko-Gross

The Perry Bible Fellowship Almanack by Nicholas Gurewitch

Pim & Francie by Al Columbia

Stitches by David Small

Terry and the Pirates, vol.6 by Milton Caniff

West Coast Blues by Jean-Patrick Manchette and Jacques Tardi

Art Books

I also want to acknowledge a few great books that came out in 2009 that are more "art books" than comics, but which contain comics and/or have a strong relationship to comics. All of these books are really beautiful and quite worth investing in a big new coffee table on which to display them.

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics

The Art of Tony Millionaire

Hot Potatoe by Marc Bell

Wayne White: Maybe Now I'll Get the Respect I So Richly Deserve

I was going to do the top 10 comics of 2009, but I just couldn't limit myself to 10. So here are my top 15. Some big caveats going in. First, there are comics that came out this year that look really good that I haven't read yet. (For example, the new Joe Sacco book.) There are also probably comics that came out this year that are really good that I just don't know about. And finally, this list is personal and idiosyncratic. It is the list of a guy who values art comics and alternative comics far more than mainstream comics. My tastes were formed in the 80s and 90s, and I think that shows. I am someone who loves the comic strip form, especially as practiced before World War II. Also, I have found over the past few years that I haven't been reading many comic books. So the only comic book on this list is Multiforce (and calling it a comic book is kind of a stretch).So with that in mind, here we go!

The Top 15

1) Asterios Polyp by David Mazzucchelli. See my review here. A beautiful, rigorously structured, funny and moving book.

2) You Are There by Jean-Claude Forest and Jacques Tardi. See my review here. This is, like so many things on my list, actually quite an old work. But this edition is the first published in English.

3) Jack Survives by Jack Moriarity. This powerful body of work was mostly published in RAW in the 80s. Moriarty approaches these comics as a life-long painter, and this edition reproduces them as paintings, not as high-contrast line drawings, which is how they were originally printed. The result is mesmerizing without detracting from the stories. The stories are kind of abstractions of early 50s manhood. A guy in a hat with his family and his house... Brilliant pieces of minimalism created with a neo-expressionist painter's brush.

4) The Book of Genesis Illustrated by Robert Crumb. Awe-inspiring. In a way, Crumb has been too faithful. Using a very literal translation of the Bible by Robert Alter as his starting point, he tries to keep interpretation to a minimum. One result is that the comic form is compromised in at least one obvious way. The Bible will have passages that read, "He said, Blah blah blah" In the Bible, there are no freestanding quotations of spoken words. So in a panel where Crumb is depicting someone speakings, there is always a little caption preceeding the word balloon that says something like, "And then Jacob said" This is really weird. What these captions are saying is being shown through the use of the visual device of the word balloon. This was just one of the awkward things that comes from including every word of a prose work in a different medium (comics). Of course, his artistry makes up for a lot of awkwardness. You can stare at this book forever. One aspect of Genesis that is really boring is the listing of names--the "begats." But Crumb, drawing all these hundreds of faces, turns that weakness of the text into an overwhelming strength--each face, so individual, implies a story, a life. It's a beautiful piece of work.

5) George Sprott (1894-1975) by Seth. This ran in the New York Times Magazine, and for this book, Seth has added some incidental art (spectacular, of course--it includes cardboard models of the buildings from the story) and two short recollections of Sprott's boyhood and youth. Seth uses a technique that I think really works better for him than telling a story as a straight narrative. Each page is its own little episode--set in its own time, focusing on a particular person. The sum of these episodes is George Sprott's awful life--an asshole whose career is an extended riff on one minor achievement of his young manhood. It is amazing how compelling this nasty character is!

6) The Complete Little Orphan Annie, vol. 3 by Harold Gray. See my review here. An unusually powerful melodrama from the depths of the Depression.

7) Popeye, vol. 4 by E.C. Segar. This is the volume with the great "Plunder Island" sequence, which introduced many of us to the genius of Segar when it was reproduced in the Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics. But the whole of this book is top-notch, Segar at his greatest. Includes a lengthy and hilarious sequence of Popeye in drag, romancing a baddie.

8) Journey, vol 2 by William Messner-Loebs. An underappreciated classic from the 80s, published in the first great flush of "independent comics" that brought us classics like Love & Rockets and Yummy Fur. MacAlistaire and the failed poet Elmer Alyn Craft (who was introduced in the first volume) are stranded in the barely there settlement of New Hope for a winter. This village is claustrophobic and full of horrible secrets. Craft is obsessed with finding them--MacAlistaire is interested only insofar as it will help him survive the winter. Messner-Loebs' drawing has lost what little polish it exhibited in the first volume. It becomes ragged and urgent here, fitting the psychologically intense and unsettling story.

9) Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, vol. 8. This is a particularly rich volume. Gould made a decision to not send Dick Tracy to war, but the war pops up. Pruneface is an enemy agent that Tracy must shut down. His most terrifying villain in this volume, however, is Mrs. Pruneface, a hulking skullfaced woman seeking revenge for her man's death. And of Tracy's iconic villains, Flattop rounds out this volume (and we meet Vitamin Flintheart, who will be a recurring character). The art is, as always, excellent.

10) Multiforce by Mat Brinkman. I've read a lot of these strips here and there, and only now realize that they all sort of fit together.This oversized, saddle-stitched book brings the whole saga together. And "saga" is the right word. Multiforce is simultaneously the kind of epic a ten-year-old boy would conceive of and at the same time the kind of art that a sophisticated product of elite art education might create. The work slithers between these two poles trickily. And Brinkman never fails to be amusing. This may remind some people of Trondheim and Sfarr's Dungeon books, which are clever and funny, but frankly feel contrived next to Multiforce. Great, weird art and storytelling.

11) Cecil and Jordon in New York by Gabrielle Bell. Very good--Bell's art is outstanding in a non-showy, matter-of-fact way. In some stories, she never shows you someone's face in a close-up, and in some of her autobiographical stories, almost ever figure is drawn full-figure--in other words you see their feet and heads in every panel they are in. The distance from the observer and the characters is pretty large. It's a weird way to tell an autobiographical story--its as if the author was pretending not to know what was going through the mind of the character. It creates an interesting contradiction, as if Bell were alienated from her earlier self. That feeling carries through in her fiction stories too. The characters seem to feel disconnected from their lives, even as they have what (on the surface) seem like pretty engaging experiences. Her characters never get happy, which can be kind of a downer. The title story even features a character who would be happier as a chair--she'd feel useful that way, and not have to struggle the way she did when she was a full-time girl.

12) Everyone Is Stupid Except For Me by Peter Bagge. This collection has been a long time coming. Peter Bagge has been doing these reportorial strips for Reason for years, and before that he did similar strips for the late, lamented web magazine Suck. His reporting is infused with his own style of humor, which will resonate with fans of Hate (like me). But what is different is that he is actually reporting here--going out, covering events, talking to participants, doing research, etc. Satirical reporting may have been around forever, but in modern times, Spy was the first big practitioner of it. Spy spawned a host of mostly online followers--Suck, of course, and nowadays websites like Gawker and Wonkette. But those sites are mostly picking up news and adding their own snarky spin. Like the writers for Spy, Bagge is going out and doing the digging himself, and like the great magazine reporters of the '60s and '70s, he puts himself in the stories. Most of this work is in service of Bagge's (and Reason's) libertarian beliefs. Don't expect him to be "fair"--he has a point of view and he is going to hammer it home. But he is a humorist first, so he is constantly mocking his own side (if they are mockable) as well as the protagonists of his stories. But if you are not a libertarian, you'll find yourself muttering "That's outrageous!" at many of Bagge's broader caricatures of liberals or conservatives. Get past that! These strips are very, very funny, and if they force you to work harder to defend your point of view against Bagge's arguments, is that bad?

13) You’ll Never Know book 1: A Good and Decent Man by Carol Tyler. Great but somewhat confused biography/memoir. Carol Tyler is attempting to tell the story of her dad in World War II. She is faced with a problem, though. Tyler's dad doesn't want to talk about a certain part of it--his time in Italy. We are given hint that he saw a literal "river of blood," and the trauma has kept him silent for decades. Even his wife doesn't know. Tyler herself is going through her own stuff--an absent husband, a beautiful teenage daughter, life. Tyler is better at short pieces, where she can focus. This is a glorious mess, but a moving and beautiful one. The format is unusual too. Tyler uses the horizontal format of a scrapbook. Also, for some reason, the whole thing is not being told in one volume. I suppose I will wait long frustrating months (and years?) for the next volume.

14) Map of My Heart by John Porcellino. I think this could have been better edited. As it is, they just reprinted whole issues of King Kat, including letters to Porcellino. This approach, however, feels consistent with the basic vibe of King Cat. The stories are slight, filled with simple joy or being alive or with small regrets. In between the stories, there are journal entries and annotations where Porcellino tells us about the arc of his marriage, his sense of failure at getting divorced, his mysterious chronic illness. etc. These are almost never the subjects of his comics. At least not directly. His work is oblique that way, but never obscure. On the contrary, emotion is right on the surface. Lots of very moving stories here.

15) Nine Ways to Disappear by Lilly Carre. This is a collection of witty little stories. Some have the flavor of modern fairy tales ("The Pearl"), and all of them have an other-worldly quality. She uses a primitive panel progression--one panel per page, like the old woodcut guys (Lynd Ward, Franz Masereel). To emphasize the separateness of each panel, each one has a decorative border (recalling Lynda Barry, perhaps). But the stories flow perfectly well, and doing it this way made me linger a bit over each panel. Which is nice, because they are lovely. My favorite story is "Wide Eyes", the story of a man who falls in love with a woman with widely-spaced eyes, but feeling oppressed by them, finds he can hide from her by standing very close to her face, between her eyes and apparently outside her field of vision. My favorite character is the only recurring one, a lonely storm grate.

(A little side note--of the top 15 books, four were published by Fantagraphics, three by Drawn & Quarterly, three by IDW, and one each by Norton, Buenaventura Press, Pantheon, Little Otsu, and Picturebox.)

Honorable mention

Here are some other 2009 comics I liked.

The Best American Comics 2009 edited by Charles Burns

The Cartoon History of the Modern World vol. 2 by Larry Gonick

The Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, vol. 7

The Complete Little Orphan Annie, vol. 2 by Harold Gray

A Drifiting Life by Yoshiharu Tatsumi

Ho! by Ivan Brunetti

Humbug by Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Davis, Al Jaffee, Arnold Roth, Will Elder, etc.

Key Moments from the History of Comics by François Ayroles

Low Moon by Jason

Masterpiece Comics by R. Sikoryak

A Mess of Everything by Miss Lasko-Gross

The Perry Bible Fellowship Almanack by Nicholas Gurewitch

Pim & Francie by Al Columbia

Stitches by David Small

Terry and the Pirates, vol.6 by Milton Caniff

West Coast Blues by Jean-Patrick Manchette and Jacques Tardi

Art Books

I also want to acknowledge a few great books that came out in 2009 that are more "art books" than comics, but which contain comics and/or have a strong relationship to comics. All of these books are really beautiful and quite worth investing in a big new coffee table on which to display them.

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics

The Art of Tony Millionaire

Hot Potatoe by Marc Bell

Wayne White: Maybe Now I'll Get the Respect I So Richly Deserve

Saturday, November 28, 2009

You Are There by Jacques Tardi

Robert Boyd

You Are There by Jacques Tardi and Jean-Claude Forest

by Jacques Tardi and Jean-Claude Forest

Of all the comics published in 2009, none has deserved more acclaim yet faced more indifference (as far as I can tell) than You Are There. For reasons I don't understand, Jacques Tardi is tough for American readers to take. It's not like his work has lacked for American publishers--starting in the 70s, his Polonius was published in Heavy Metal. Fantagraphics, the publisher of You Are There, has made prior attempts at translating Tardi--a Nestor Burma mystery in Prime Cuts and Griffu in Pictopia (I was the editor of that one). NBM published two delightful color albums featuring Adele Blanc-Sec, and her adventures continued for hundreds of pages in Dark Horse's Cheval Noir comic series. iBooks published another excellent Nestor Burma story in a graphic novel format, and Drawn & Quarterly has published several chapters from Tardi's brutal yet beautiful It Was The War of the Trenches. In these works, American readers got a real sense of the breadth of Tardi's work, and responded with a collective shoulder shrug. (I enjoyed all of these books and stories.)

Among French readers, You Are There appears to be held in special regard. Publisher/translator Kim Thompson has said that Tardi holds a place with the current generation of alternative French comics similar to that held by Crumb here in the U.S. Writer Jean-Claude Forest is also a legend in the history of comics, most famous for creating Barbarella in 1962. As I write this, I realize I am setting up the reader for two possible reviews. One is that after all this build up, I tell you that You Are There is ironically a dud. The other is that it lives up to my high opinion of Tardi's work. The good news, in short, is that the latter option is true. And if you don't want to read anything about the plot of You Are There, take my word about its excellence and stop reading right here.

The protagonist is Arthur There, last son of a family that once owned Mornemont, a vast estate which has somehow been subdivided into smaller estates by various rich families, leaving There with possession of the walls between the estates. He lives in a narrow house perched on one of the walls.

He earns a meager living opening gates for the various estate owners (making certain never to touch the ground as he does so)--in this small way, they are still dependent on him. They are his gates after all. Most of his income goes to his legal team (including the president of the bar association) who are charged with reclaiming title for There to Mornemont.

But as you can see, they are mainly showering There with legal bullshit in order to keep him paying his retainer. This particular legal meeting takes place on a boat--the only place where There can leave his walls is to step onto docked boats (Mornemont lies on the shore of a large lake--I couldn't tell for certain, but it may be an island in the lake). Consequently, he gets his sustenance from a grocery boat. The captain of this boat is the last in a long line of grocer-sailors.

You can see that this story doesn't exactly pretend to be realistic. (That said, There's bizarre property holdings, the walls between the estates, have all kinds of analogues in the real world. I would not be surprised if Forest read such a story of real estate absurdity and was inspired by it to write this tale.) Once the bizarre circumstances of There's life are outlined, Forest brings in the classic complication--love. There sees Julie Maillard (daughter of one of the estate owners) nude through a window. Julie is a bit of a tease (and There is no prize catch.) But There is so inexperienced and shy, she must take the initiative. Her post-coital monologue is hilarious, all the more so because Tardi portrays There's stunned amazement at what has just happened in a very surreal way.

Meanwhile, far from Mornemont, the government is in trouble. They are about to lose their majority, and when that happens, their corruption will be revealed. They learn that in 1784, the king granted a certain Marquis sovereignty over his tiny fiefdom in exchange for services rendered in Golconda. The Marquis nominally retained sovereignty after the Revolution (at which point he became a mere citizen), and that sovereignty has passed down, father to son, to the final heir. That heir is Arthur There. The government therefore concocts a plan to help There regain his land, and for the government to go into internal exile in Mornemont when they lose the the next election. Exile from which they cannot be extradited, where they pull the strings of their new puppet sovereign. As it turns out, they arrive at just the right moment, when the landowners, tired of Arthur's antics, have attacked his walls. They are no match for the power of the French government, though.

But Arthur doesn't end up happy--the landowners are expelled and Arthur owns all the land again. The government withdraws when they unexpectedly win the election. But his joy has been ruined by Julie's promiscuity and the fundamental impossibility of happiness.

Like many of Tardi's works, You Are There is set in the early 20th century. It doesn't pay to try to locate a precise year for this work. Forest and Tardi aren't creating a historical novel per se. They aren't realists (although Tardi is capable of creating realistic fictions.) They use history as an absurd jumping off point, much as Mark Helprin did in A Soldier of the Great War or Italo Calvino did in The Cloven Viscount, The Nonexistent Knight, and The Baron of the Trees.

Is this a satire on property and heredity? It can be read that way. Part of There's problem is that his "victory" means Julie's dispossession. What delights me is not the meaning of the work, but the bizarre world Forest and Tardi have created. Tardi's art, which combines the liveliness and simplicity of the best cartooning with a well-observed realism is perfect for this kind of surreal tale.

I hope this new series of Tardi books (this one and West Coast Blues are the first) will spark new interest in this great cartoonist among American readers. His work deserves to be read and will endless reward readers who seek it out.

You Are There

Of all the comics published in 2009, none has deserved more acclaim yet faced more indifference (as far as I can tell) than You Are There. For reasons I don't understand, Jacques Tardi is tough for American readers to take. It's not like his work has lacked for American publishers--starting in the 70s, his Polonius was published in Heavy Metal. Fantagraphics, the publisher of You Are There, has made prior attempts at translating Tardi--a Nestor Burma mystery in Prime Cuts and Griffu in Pictopia (I was the editor of that one). NBM published two delightful color albums featuring Adele Blanc-Sec, and her adventures continued for hundreds of pages in Dark Horse's Cheval Noir comic series. iBooks published another excellent Nestor Burma story in a graphic novel format, and Drawn & Quarterly has published several chapters from Tardi's brutal yet beautiful It Was The War of the Trenches. In these works, American readers got a real sense of the breadth of Tardi's work, and responded with a collective shoulder shrug. (I enjoyed all of these books and stories.)

Among French readers, You Are There appears to be held in special regard. Publisher/translator Kim Thompson has said that Tardi holds a place with the current generation of alternative French comics similar to that held by Crumb here in the U.S. Writer Jean-Claude Forest is also a legend in the history of comics, most famous for creating Barbarella in 1962. As I write this, I realize I am setting up the reader for two possible reviews. One is that after all this build up, I tell you that You Are There is ironically a dud. The other is that it lives up to my high opinion of Tardi's work. The good news, in short, is that the latter option is true. And if you don't want to read anything about the plot of You Are There, take my word about its excellence and stop reading right here.

The protagonist is Arthur There, last son of a family that once owned Mornemont, a vast estate which has somehow been subdivided into smaller estates by various rich families, leaving There with possession of the walls between the estates. He lives in a narrow house perched on one of the walls.

He earns a meager living opening gates for the various estate owners (making certain never to touch the ground as he does so)--in this small way, they are still dependent on him. They are his gates after all. Most of his income goes to his legal team (including the president of the bar association) who are charged with reclaiming title for There to Mornemont.

But as you can see, they are mainly showering There with legal bullshit in order to keep him paying his retainer. This particular legal meeting takes place on a boat--the only place where There can leave his walls is to step onto docked boats (Mornemont lies on the shore of a large lake--I couldn't tell for certain, but it may be an island in the lake). Consequently, he gets his sustenance from a grocery boat. The captain of this boat is the last in a long line of grocer-sailors.

You can see that this story doesn't exactly pretend to be realistic. (That said, There's bizarre property holdings, the walls between the estates, have all kinds of analogues in the real world. I would not be surprised if Forest read such a story of real estate absurdity and was inspired by it to write this tale.) Once the bizarre circumstances of There's life are outlined, Forest brings in the classic complication--love. There sees Julie Maillard (daughter of one of the estate owners) nude through a window. Julie is a bit of a tease (and There is no prize catch.) But There is so inexperienced and shy, she must take the initiative. Her post-coital monologue is hilarious, all the more so because Tardi portrays There's stunned amazement at what has just happened in a very surreal way.

Meanwhile, far from Mornemont, the government is in trouble. They are about to lose their majority, and when that happens, their corruption will be revealed. They learn that in 1784, the king granted a certain Marquis sovereignty over his tiny fiefdom in exchange for services rendered in Golconda. The Marquis nominally retained sovereignty after the Revolution (at which point he became a mere citizen), and that sovereignty has passed down, father to son, to the final heir. That heir is Arthur There. The government therefore concocts a plan to help There regain his land, and for the government to go into internal exile in Mornemont when they lose the the next election. Exile from which they cannot be extradited, where they pull the strings of their new puppet sovereign. As it turns out, they arrive at just the right moment, when the landowners, tired of Arthur's antics, have attacked his walls. They are no match for the power of the French government, though.

But Arthur doesn't end up happy--the landowners are expelled and Arthur owns all the land again. The government withdraws when they unexpectedly win the election. But his joy has been ruined by Julie's promiscuity and the fundamental impossibility of happiness.

Like many of Tardi's works, You Are There is set in the early 20th century. It doesn't pay to try to locate a precise year for this work. Forest and Tardi aren't creating a historical novel per se. They aren't realists (although Tardi is capable of creating realistic fictions.) They use history as an absurd jumping off point, much as Mark Helprin did in A Soldier of the Great War or Italo Calvino did in The Cloven Viscount, The Nonexistent Knight, and The Baron of the Trees.

Is this a satire on property and heredity? It can be read that way. Part of There's problem is that his "victory" means Julie's dispossession. What delights me is not the meaning of the work, but the bizarre world Forest and Tardi have created. Tardi's art, which combines the liveliness and simplicity of the best cartooning with a well-observed realism is perfect for this kind of surreal tale.

I hope this new series of Tardi books (this one and West Coast Blues are the first) will spark new interest in this great cartoonist among American readers. His work deserves to be read and will endless reward readers who seek it out.

Labels:

comics,

Jacques Tardi,

Jean-Claude Forest

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)