Today I report on the R. Crumb Sketchbook vol. 2: Sept. 1968 - Jan. 1975. Time has forced me to reconsider Robert Crumb, who I used to esteem unreservedly. I think you'll see why I re-evaluate the man and his art in this report. I ordered this book directly from the publisher, Taschen. My go-to bookseller, Bookshop.com, doesn't have all the sketchbooks available. I only see volume 1 and volume 5 in their online store.

Showing posts with label Robert Crumb. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Robert Crumb. Show all posts

Wednesday, February 24, 2021

Robert Boyd's Book Report: R. Crumb Sketchbook vol. 2

Labels:

Robert Crumb

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

Lone Star Link Explosion

by Robert Boyd

painting by Song Byeock

From Prop Art to Pop Art. Song Byeock was a North Korean artist--privileged, a Communist Party member, a painter of propaganda images. But as famine swept North Korea, he decided to defect. He failed in his first attempt (which claimed the life of his father), was captured and tortured, but finally made the crossing over the Tumen River into China. Now he paints bitterly ironic images of North Korea. The one above depicts the late Kim Jong Il surrounded by the child-beggars who swarm North Korea's railway stations. This article is is excellent, and if You have further interest in the subject of North Korean life (as told by defectors), I recommend the book Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea. ["After escape from North Korea, artist turns from propaganda to pop art," Paul Ferguson, CNN, March 25, 2012]

Eric Minh Swenson, Mat Gleason: The Hung Juror

I, The Jury. Coagula critic Mat Gleason stars in an amusing video The Hung Juror (directed by Eric Minh Swenson), as well as writing about his experience as the juror for the 23rd annual juried art show at the Contemporary Art Center in Las Vegas. I've been reading Judgement of Paris: the Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism, which gives great detail about how the Paris Salon worked in the 1860s and how key the selection of jurors was in any given year. We see this in Lawndale's Big Show, how each year feels a little different based at least partly on the tastes of the different jurors. [Mat Gleason, "Artist Juried Shows--Winner Take All," Huffington Post, 4/9/2012)

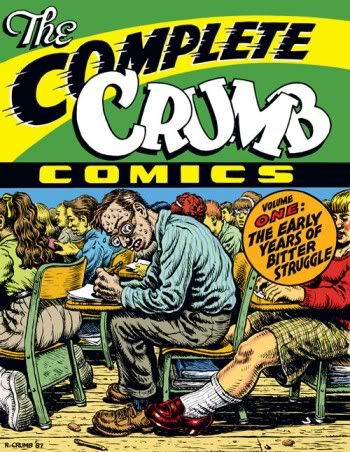

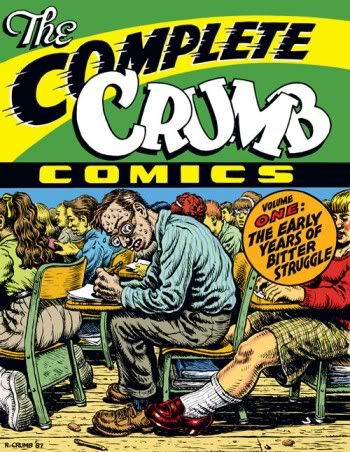

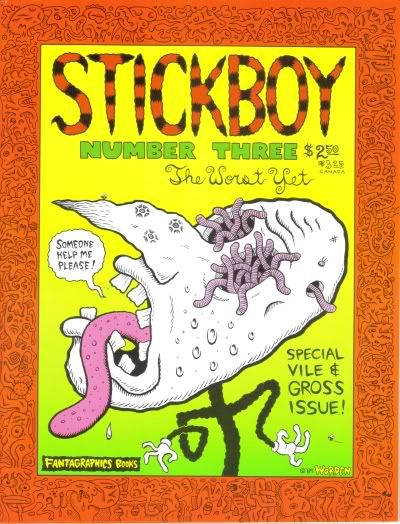

Robert Crumb, The Complete Crumb Comics volume 1, 1987

The child is the father of man.A long time ago, I was an editor. One of the things I edited was a series of books called The Complete Crumb Comics. I took this on after the original series editor, Robert Fiore, left. A a series, it's a little like a catalogue raisonné, but unlike most catalogues raisonnés, it included two full volumes of Robert Crumb's juvenile work and other early work. (In contrast, the earliest work in this amazing Ed Ruscha catalogue raisonné is from 1958, and it's clearly a mature work.) I never could understand the value of showing this childhood work until I read Jeet Heer's examination of the work--15 years after publication. Heer deftly links the work to Crumb's own dysfunctional family environment (which was revealed in the documentary Crumb), and to Crumb's own later obsessions. And Heer uses the comics themselves to link Crumb's later obsessions to his own harrowing childhood. It's an excellent work of criticism. [Jeet Heer, "Crumb in the Beginning," The Comics Journal, April 5, 2012]

Participating in your own oppression. I've only done one internship in my life, and I was paid well for it. It always seems alien to me that people in the art world will intern for free. Occupy Wall Street’s Arts & Labor working group agrees--they asked the New York Foundation for the Arts to stop posting ads for unpaid internships for for-profit institutions. (I'm personally opposed to unpaid internships at non-profit institutions, as well.) NYFA has not complied so far. Why do people accept unpaid work like this? The answer is in research by sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh. He discovered that low level drug dealers accept low wages in hopes of eventually getting the high wages of top-level gangsters. But the number of slots for upper-level gangsters is very low, and the number of people who want to enter this industry is very high. You see the same thing in sports--marketing majors who can get a decent salary working for, say, Yum Brands will get paid half that salary to do the same work for the Buccaneers. In short, a glamorous industry (sports, movies, art, drugs) has so many people wanting to work for it that many of them are actually willing to work for free. Hence the unpaid internships in the arts. (Not to mention the whole student-athlete scam for college football and basketball players.) The problem with this is that the only people who can afford to take unpaid internships are relatively rich kids. A brilliant young art historian from a working class family simply can't spend a year working for nothing. Unpaid internships reinforce the economic elitism of the arts. [Hrag Vartanian, "The Art World Plague of Unpaid Internships," Hyperallergic, April 6, 2012]

painting by Song Byeock

From Prop Art to Pop Art. Song Byeock was a North Korean artist--privileged, a Communist Party member, a painter of propaganda images. But as famine swept North Korea, he decided to defect. He failed in his first attempt (which claimed the life of his father), was captured and tortured, but finally made the crossing over the Tumen River into China. Now he paints bitterly ironic images of North Korea. The one above depicts the late Kim Jong Il surrounded by the child-beggars who swarm North Korea's railway stations. This article is is excellent, and if You have further interest in the subject of North Korean life (as told by defectors), I recommend the book Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea. ["After escape from North Korea, artist turns from propaganda to pop art," Paul Ferguson, CNN, March 25, 2012]

Eric Minh Swenson, Mat Gleason: The Hung Juror

I, The Jury. Coagula critic Mat Gleason stars in an amusing video The Hung Juror (directed by Eric Minh Swenson), as well as writing about his experience as the juror for the 23rd annual juried art show at the Contemporary Art Center in Las Vegas. I've been reading Judgement of Paris: the Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism, which gives great detail about how the Paris Salon worked in the 1860s and how key the selection of jurors was in any given year. We see this in Lawndale's Big Show, how each year feels a little different based at least partly on the tastes of the different jurors. [Mat Gleason, "Artist Juried Shows--Winner Take All," Huffington Post, 4/9/2012)

Robert Crumb, The Complete Crumb Comics volume 1, 1987

The child is the father of man.A long time ago, I was an editor. One of the things I edited was a series of books called The Complete Crumb Comics. I took this on after the original series editor, Robert Fiore, left. A a series, it's a little like a catalogue raisonné, but unlike most catalogues raisonnés, it included two full volumes of Robert Crumb's juvenile work and other early work. (In contrast, the earliest work in this amazing Ed Ruscha catalogue raisonné is from 1958, and it's clearly a mature work.) I never could understand the value of showing this childhood work until I read Jeet Heer's examination of the work--15 years after publication. Heer deftly links the work to Crumb's own dysfunctional family environment (which was revealed in the documentary Crumb), and to Crumb's own later obsessions. And Heer uses the comics themselves to link Crumb's later obsessions to his own harrowing childhood. It's an excellent work of criticism. [Jeet Heer, "Crumb in the Beginning," The Comics Journal, April 5, 2012]

Participating in your own oppression. I've only done one internship in my life, and I was paid well for it. It always seems alien to me that people in the art world will intern for free. Occupy Wall Street’s Arts & Labor working group agrees--they asked the New York Foundation for the Arts to stop posting ads for unpaid internships for for-profit institutions. (I'm personally opposed to unpaid internships at non-profit institutions, as well.) NYFA has not complied so far. Why do people accept unpaid work like this? The answer is in research by sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh. He discovered that low level drug dealers accept low wages in hopes of eventually getting the high wages of top-level gangsters. But the number of slots for upper-level gangsters is very low, and the number of people who want to enter this industry is very high. You see the same thing in sports--marketing majors who can get a decent salary working for, say, Yum Brands will get paid half that salary to do the same work for the Buccaneers. In short, a glamorous industry (sports, movies, art, drugs) has so many people wanting to work for it that many of them are actually willing to work for free. Hence the unpaid internships in the arts. (Not to mention the whole student-athlete scam for college football and basketball players.) The problem with this is that the only people who can afford to take unpaid internships are relatively rich kids. A brilliant young art historian from a working class family simply can't spend a year working for nothing. Unpaid internships reinforce the economic elitism of the arts. [Hrag Vartanian, "The Art World Plague of Unpaid Internships," Hyperallergic, April 6, 2012]

Labels:

internships,

Jeet Heer,

Mat Gleason,

Robert Crumb,

Song Byeock

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Kim Dingle at Front Gallery

by Robert Boyd

The ecology of art means that sometimes galleries close and sometimes now ones open. I was driving by the old Apama Mackey and saw a "for sale" sign on its cool container-car exterior. Sad but it happens. It's a tough business, making a gallery go. More hopeful are the appearance of two new galleries on the scene. Cardoza is located where The Temporary Space used to be. What's exciting there is that Mark Flood has a show coming up on October 14. Ironically, Christopher Cascio has a show opening there in November--he showed there when it was the Temporary Space.

In the meantime, Front Gallery had its inaugural exhibit on Saturday, October 8. The Front Gallery is so named, I'm guessing, because it is the front room of artist Sharon Engelstein's house. It's my experience that galleries in houses are kind of half-assed affairs. If people live in the house, it feels like you are walking into someone's private living space. You find yourself stumbling over furniture. If the house has been converted to a gallery, the rooms often feel like they are the wrong dimensions--ceilings too low, the hallways between "gallery" rooms are awkward, there are awkward windows, etc. This awkwardness is in part due to the fact that I have a certain expectation of a gallery--big room with a high ceiling, painted white.

And there is no doubt when you walk into Front Gallery that it is quite literally a front parlour. But it worked as a gallery for this show because the art was perfectly in scale with the room and because it was clearly separate from the rest of the house.

Kim Dingle installed at Front Gallery

So not only does Front Gallery look great, but it started off its life with a completely excellent show. Kim Dingle is a Los Angeles artist who is best known for her drawings and paintings of hyper-active girls--Priss, the Wild Girls, Fatty and Fudge. I believe the girls portrayed here are Fatty and Fudge.

Kim Dingle, untitled, oil on vellum, 2011

She has said all of the girls are based on herself, but also specifically references Wadow Dingle, her neice, who was born with brain damage that caused violent outbursts during her childhood. That's what we see in these drawings--explosions of violent energy.

Kim Dingle, untitled, oil on vellum, 2011

The medium is interesting. Anyone who has painted with oil paint knows how slippery it is (unlike acrylic paint, which is sticky). And vellum, a transparent, ultrasmooth drawing surface, is also quite slippery (unlike, say, canvas). Using oil on vellum allows an artist to paint in two ways simultaneously--to put paint down onto the vellum and to pull it off. In short, erasing paint is potentially as expressive as adding paint. That's what we see in these pieces.

Kim Dingle, untitled, oil on vellum, 2011

The double-slipperiness of the medium encourages a sketchy, expressionist approach, which suits the subject. There's just enough there to show you what you need to see. In the vigor, violence and economy, these paintings remind me the comic strips of the 1920s and 30s--not the pretty, highly rendered ones like Price Valiant or Little Nemo, but the more streetwise, working class comics like Popeye, The Bungle Family, and Krazy Kat.

Kim Dingle, untitled, oil on vellum, 2011

The west wall of Front Gallery is where the fireplace is. So for this show, the works on that wall were distinct from the Dingle pieces on the north and east walls. Over the mantle was this drawing:

Robert Crumb, untitled, ink on a placemat, 2000

Robert Crumb is another artist whose work recalls those early 20th century newspaper comic strip artists. But as he has gotten older, his work has become more detailed and baroque. One can see that in this sketch. These placemat sketches were done in restaurants in the small town in France where he lives. He is, obviously, a compulsive doodler. (So compulsive that three books of these sketches have been published.) It's astonishing to look at this or to read the books and realize that this is what he does while sitting around waiting for his pizza to be ready.

Sharon Engelstein, various maquettes

Finally, on the small shelves beside the fireplace, Engelstein placed what appear to be maquettes for some of her own pieces.It's interesting to see them so small and devoid of color.

In short, a successful first show for Front Gallery.

The ecology of art means that sometimes galleries close and sometimes now ones open. I was driving by the old Apama Mackey and saw a "for sale" sign on its cool container-car exterior. Sad but it happens. It's a tough business, making a gallery go. More hopeful are the appearance of two new galleries on the scene. Cardoza is located where The Temporary Space used to be. What's exciting there is that Mark Flood has a show coming up on October 14. Ironically, Christopher Cascio has a show opening there in November--he showed there when it was the Temporary Space.

In the meantime, Front Gallery had its inaugural exhibit on Saturday, October 8. The Front Gallery is so named, I'm guessing, because it is the front room of artist Sharon Engelstein's house. It's my experience that galleries in houses are kind of half-assed affairs. If people live in the house, it feels like you are walking into someone's private living space. You find yourself stumbling over furniture. If the house has been converted to a gallery, the rooms often feel like they are the wrong dimensions--ceilings too low, the hallways between "gallery" rooms are awkward, there are awkward windows, etc. This awkwardness is in part due to the fact that I have a certain expectation of a gallery--big room with a high ceiling, painted white.

And there is no doubt when you walk into Front Gallery that it is quite literally a front parlour. But it worked as a gallery for this show because the art was perfectly in scale with the room and because it was clearly separate from the rest of the house.

Kim Dingle installed at Front Gallery

So not only does Front Gallery look great, but it started off its life with a completely excellent show. Kim Dingle is a Los Angeles artist who is best known for her drawings and paintings of hyper-active girls--Priss, the Wild Girls, Fatty and Fudge. I believe the girls portrayed here are Fatty and Fudge.

Kim Dingle, untitled, oil on vellum, 2011

She has said all of the girls are based on herself, but also specifically references Wadow Dingle, her neice, who was born with brain damage that caused violent outbursts during her childhood. That's what we see in these drawings--explosions of violent energy.

Kim Dingle, untitled, oil on vellum, 2011

The medium is interesting. Anyone who has painted with oil paint knows how slippery it is (unlike acrylic paint, which is sticky). And vellum, a transparent, ultrasmooth drawing surface, is also quite slippery (unlike, say, canvas). Using oil on vellum allows an artist to paint in two ways simultaneously--to put paint down onto the vellum and to pull it off. In short, erasing paint is potentially as expressive as adding paint. That's what we see in these pieces.

Kim Dingle, untitled, oil on vellum, 2011

The double-slipperiness of the medium encourages a sketchy, expressionist approach, which suits the subject. There's just enough there to show you what you need to see. In the vigor, violence and economy, these paintings remind me the comic strips of the 1920s and 30s--not the pretty, highly rendered ones like Price Valiant or Little Nemo, but the more streetwise, working class comics like Popeye, The Bungle Family, and Krazy Kat.

Kim Dingle, untitled, oil on vellum, 2011

The west wall of Front Gallery is where the fireplace is. So for this show, the works on that wall were distinct from the Dingle pieces on the north and east walls. Over the mantle was this drawing:

Robert Crumb, untitled, ink on a placemat, 2000

Robert Crumb is another artist whose work recalls those early 20th century newspaper comic strip artists. But as he has gotten older, his work has become more detailed and baroque. One can see that in this sketch. These placemat sketches were done in restaurants in the small town in France where he lives. He is, obviously, a compulsive doodler. (So compulsive that three books of these sketches have been published.) It's astonishing to look at this or to read the books and realize that this is what he does while sitting around waiting for his pizza to be ready.

Sharon Engelstein, various maquettes

Finally, on the small shelves beside the fireplace, Engelstein placed what appear to be maquettes for some of her own pieces.It's interesting to see them so small and devoid of color.

In short, a successful first show for Front Gallery.

Labels:

drawing,

Kim Dingle,

painting,

Robert Crumb,

sculpture,

Sharon Engelstein

Friday, October 22, 2010

Homage to R. Crumb, My Father

Rebecca Warren, Homage to R. Crumb, My Father, reinforced clay, MDF, wheels, 2003

I don't have much to say about this Rebecca Warren sculpture except that I found it very amusing. When I looked at the photo, I instantly thought, "That ass and that nipple look really Crumb-like." So I had to laugh when I read the title.

Labels:

comics,

Rebecca Warren,

Robert Crumb,

sculpture

Saturday, August 7, 2010

Charles Boucher and Patrick Rosenkranz on Robert Crumb, Carl Barks, and Basil Wolverton

My old friend Charlie Boucher (proprietor of Portland's great shop CounterMedia) and Patrick Rosenkranz discuss the influence of two Oregonian cartoonists, Carl Barks and Basil Wolverton, on Robert Crumb.

(Hat tip to Fantagraphics.)

(Hat tip to Fantagraphics.)

Labels:

Basil Wolverton,

Carl Barks,

comics,

Robert Crumb

Monday, July 12, 2010

The Great God Pekar Is Dead

Robert Boyd

One of my comics heroes died today. I never met Harvey Pekar, creator of the great comic book American Splendor, in person, but I spoke to him on the phone numerous times when I was working for Fantagraphics. At the time, he was engaged in a very slow-moving debate with critic Robert Fiore in the pages of The Comics Journal. (This was pre-internet. A really rambunctious public debate would last months due to the infrequency of the magazine.) He was calling up a lot and for a while, I was the semi-designated Harvey-handler. He would talk your ear off, which was fine by me. I had been a fan of Pekar's for a long time.

I first encountered his stuff in the early 80s. It was definitely part of my alternative comics awakening. It mapped out a way to use comics that I had never seen before. And for good reason--Pekar's matter-of-fact autobiographical realism was something genuinely new in comics when he started doing it. Now I probably value comics that tell a real (even autobiographical) story with a richer use of metaphor--think Justin Green's Binky Brown or David B's Epileptic. But Pekar's realism was, at the time, a blinding revelation.

A lot of people will be writing about Pekar in the next few days. I want to just touch on two related aspects of his work that resonate with me to this day.

Harvey Pekar and Gerry Shamray, "Working Man's Nightmare" page 1, 1981

Pekar wrote extensively about work--his own work and other people's. This is perversely rare in comics, despite the universality of work. Pekar had an emotional and intellectual commitment to being working class. Class always pops up in his stories set in the V.A. Hospital, where he was a clerk. He needed to have that constant steady income, too. The need was psychological, as shown in the page above. Not having a job, a paycheck, structure--that was his nightmare.

It was perhaps because of this that he had conflicted relationships with the world of art. He definitely identified with artists, intellectuals and bohemians, but I think fear of operating without a net kept him from chucking it and just becoming a full-time writer.

Harvey Pekar and Kevin Brown, "Grubstreet U.S.A." page 9 (detail), 1983

This conflict between his desire for the artistic life and his fear of its uncertainties is played out in "Grubstreet U.S.A.," where he recalls meeting Wallace Shawn. His incapacity for the artist's life is demonstrated in one of his most famous stories, "American Splendor Assults the Media," with Robert Crumb. It's also one of the great rants, by the way.

For Harvey, work is what enabled him to be an artist. Losing that ability was something he dreaded--that comes through in the story "An Argument at Work."

Harvey Pekar and Gerry Shamray, "An Argument at Work" page 10, 1981 (?)

I think his work suffered after he retired. He had time to do longer pieces, but the lack of economy really hurt them. I think he felt obliged to create a narrative, when what he was good at was observing and recording moments, episodes, short stories. But if his work faltered in his later years, so what? He had produced enough great work in his early years that his place in the history of comics is assured.

(One final note: whatever happened to Gerry Shamray and Kevin Brown? They were two excellent artists for Pekar--I hope someone tracks them down and asks them about their work with Pekar. Their collaborations with Pekar deserve to be remembered.)

One of my comics heroes died today. I never met Harvey Pekar, creator of the great comic book American Splendor, in person, but I spoke to him on the phone numerous times when I was working for Fantagraphics. At the time, he was engaged in a very slow-moving debate with critic Robert Fiore in the pages of The Comics Journal. (This was pre-internet. A really rambunctious public debate would last months due to the infrequency of the magazine.) He was calling up a lot and for a while, I was the semi-designated Harvey-handler. He would talk your ear off, which was fine by me. I had been a fan of Pekar's for a long time.

I first encountered his stuff in the early 80s. It was definitely part of my alternative comics awakening. It mapped out a way to use comics that I had never seen before. And for good reason--Pekar's matter-of-fact autobiographical realism was something genuinely new in comics when he started doing it. Now I probably value comics that tell a real (even autobiographical) story with a richer use of metaphor--think Justin Green's Binky Brown or David B's Epileptic. But Pekar's realism was, at the time, a blinding revelation.

A lot of people will be writing about Pekar in the next few days. I want to just touch on two related aspects of his work that resonate with me to this day.

Harvey Pekar and Gerry Shamray, "Working Man's Nightmare" page 1, 1981

Pekar wrote extensively about work--his own work and other people's. This is perversely rare in comics, despite the universality of work. Pekar had an emotional and intellectual commitment to being working class. Class always pops up in his stories set in the V.A. Hospital, where he was a clerk. He needed to have that constant steady income, too. The need was psychological, as shown in the page above. Not having a job, a paycheck, structure--that was his nightmare.

It was perhaps because of this that he had conflicted relationships with the world of art. He definitely identified with artists, intellectuals and bohemians, but I think fear of operating without a net kept him from chucking it and just becoming a full-time writer.

Harvey Pekar and Kevin Brown, "Grubstreet U.S.A." page 9 (detail), 1983

This conflict between his desire for the artistic life and his fear of its uncertainties is played out in "Grubstreet U.S.A.," where he recalls meeting Wallace Shawn. His incapacity for the artist's life is demonstrated in one of his most famous stories, "American Splendor Assults the Media," with Robert Crumb. It's also one of the great rants, by the way.

For Harvey, work is what enabled him to be an artist. Losing that ability was something he dreaded--that comes through in the story "An Argument at Work."

Harvey Pekar and Gerry Shamray, "An Argument at Work" page 10, 1981 (?)

I think his work suffered after he retired. He had time to do longer pieces, but the lack of economy really hurt them. I think he felt obliged to create a narrative, when what he was good at was observing and recording moments, episodes, short stories. But if his work faltered in his later years, so what? He had produced enough great work in his early years that his place in the history of comics is assured.

(One final note: whatever happened to Gerry Shamray and Kevin Brown? They were two excellent artists for Pekar--I hope someone tracks them down and asks them about their work with Pekar. Their collaborations with Pekar deserve to be remembered.)

Labels:

comics,

Gerry Shamray,

Harvey Pekar,

Kevin Brown,

Robert Crumb

Friday, January 29, 2010

New Acquisitions--J.R. Williams and Dennis Worden

Last year, as far as comics art went, I collected mostly classic comic strips. This year, I am going to deliberately try to collect underground, alternative and art comics original artwork. I started off with a bit of a windfall--11 pages by two artists, both of whom were key figures in the "newave" comics scene of the 1980s.

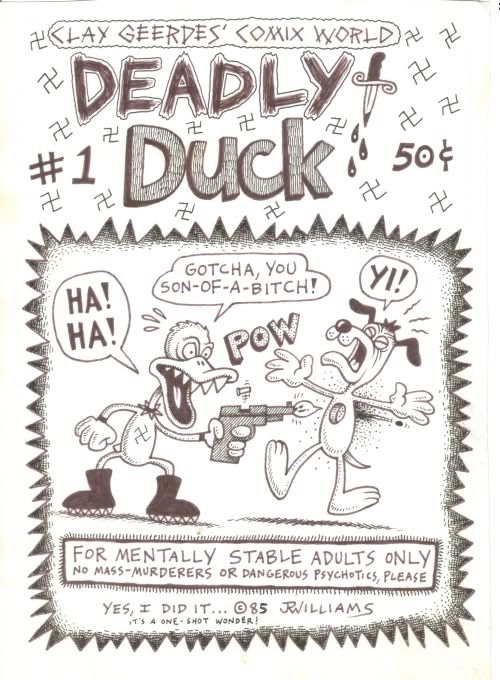

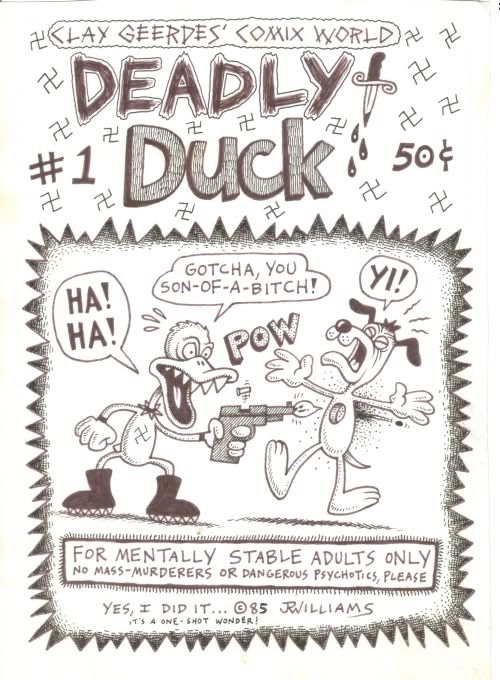

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck cover, 1985

J.R. Williams is an artist from Portland, Oregon. The pages here are from a minicomic he did in 1985 for Clay Geerdes Comix World. Clay Geerdes was an impresario of minicomics, publishing comics for many artists at the time.

What are minicomics? I guess the strictest definition would be that they were xeroxed comics printed on a piece of letter-sized paper folded over once then again to create a 4 1/4" x 5 1/2" 8-page booklet. But in general, minicomics has come to mean any self-published, micro-print-run comic (usually xeroxed). Minicomics arose with the rise of inexpensive and ubiquitous photocopiers in the 1970s. The people who drew them were amateur cartoonists inspired by the underground comics of the '60s. They formed their own networks through the mail, which in turn lead to an international movement of minicomics. (Minicomics can be seen as a subset of the zine movement of the same period. And many fans and practitioners connected to one another through the zine magazine, Factsheet Five.)

In the early 80s, minicomics were also called "newave" comics. (There is a massive collection of "Newave" comics coming out presently from Fantagraphics Books.) That's the term under which I first became aware of them, through the great comics critic Dale Luciano's mammoth survey of the "newave" scene that ran in several issues of The Comics Journal. Later, when I worked for Fantagraphics, I started writing a column about minicomics called "Minimalism" for The Comics Journal. I wrote it from 1992 to 1996, but it continues to this day, amazingly.

Many of the minicomics artists were really talented. They did minicomics for a variety of reasons, but for some of them, one reason was a lack of venues where they could get their work published commercially. The undergrounds pretty much died in the 1970s, and nothing took their place until the 80s. In the case of J.R. Williams, he found a home at Fantagraphics, where he had an ongoing series. But unlike many of his minicomics peers, he was a professional artist. When I first met him, he was working as an animator in Portland. He later moved up to Seattle to draw full time, and I later hired him to write a comic for me (Welcome to the Little Shop of Horrors).

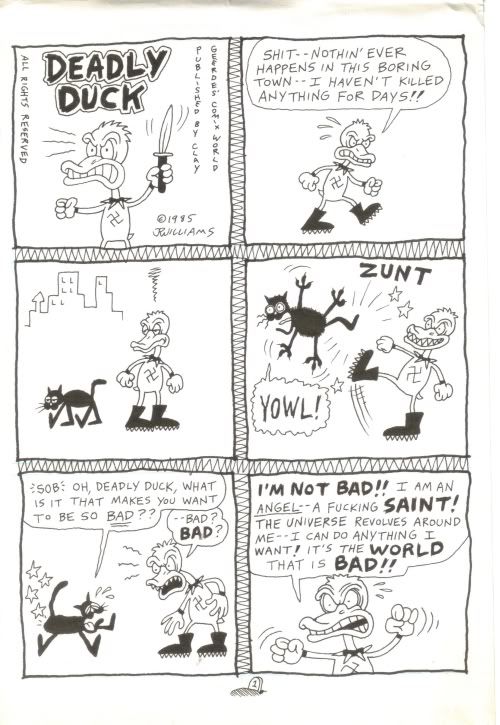

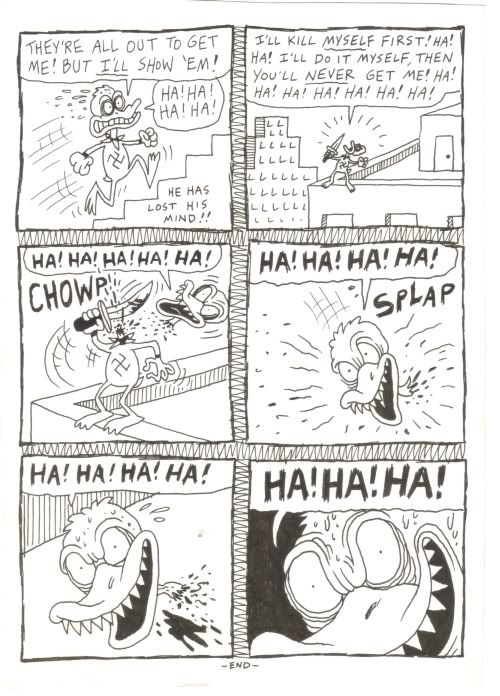

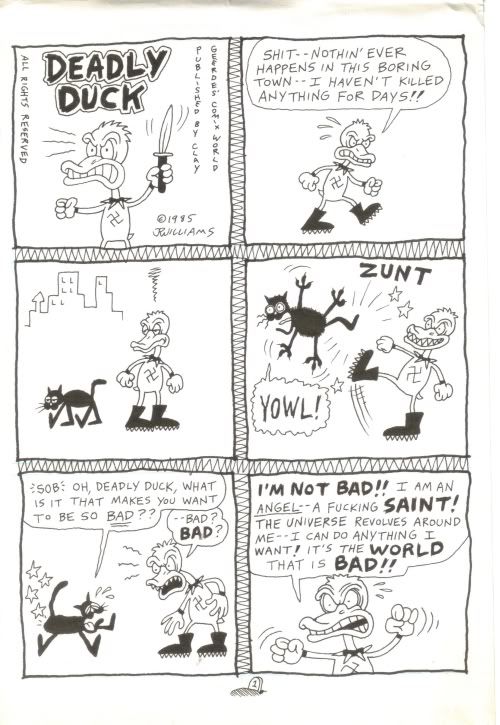

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck page 1, 1985

Deadly Duck was published in the classic minicomics format. Williams' originals are "two up"--twice the size of the printed pages. His minimal drawing style is highly appropriate to the medium in which he is working, as is his sole idea in this story. In seven tiny pages, you can't put in much plot or characterization. But it's a good size for barbaric yawps like this.

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck page 7, 1985

I was able to buy all eight pages directly from Williams. They are funny and drawn really well--perfect examples of what minicomics were all about in the 1980s.

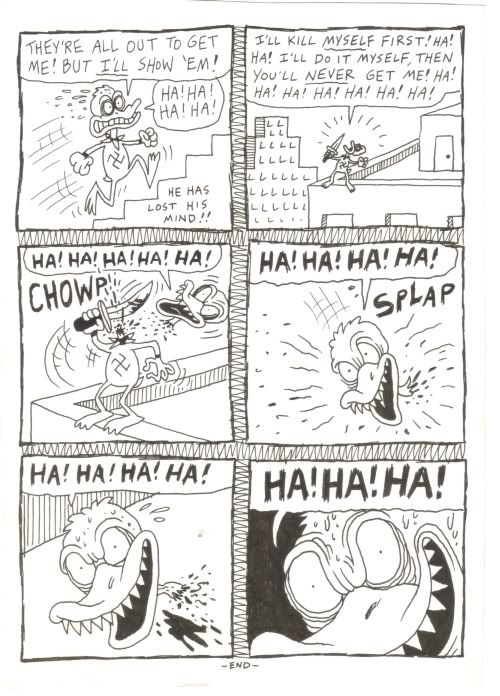

Dennis Worden comes out of the same milieu as Williams. He was from the San Diego area. He started getting published in Weirdo, had comics published by Fantagraphics and other publishers, and now does paintings, which he will happily sell to you.

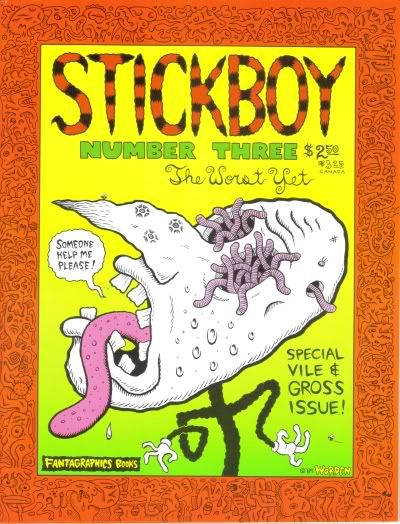

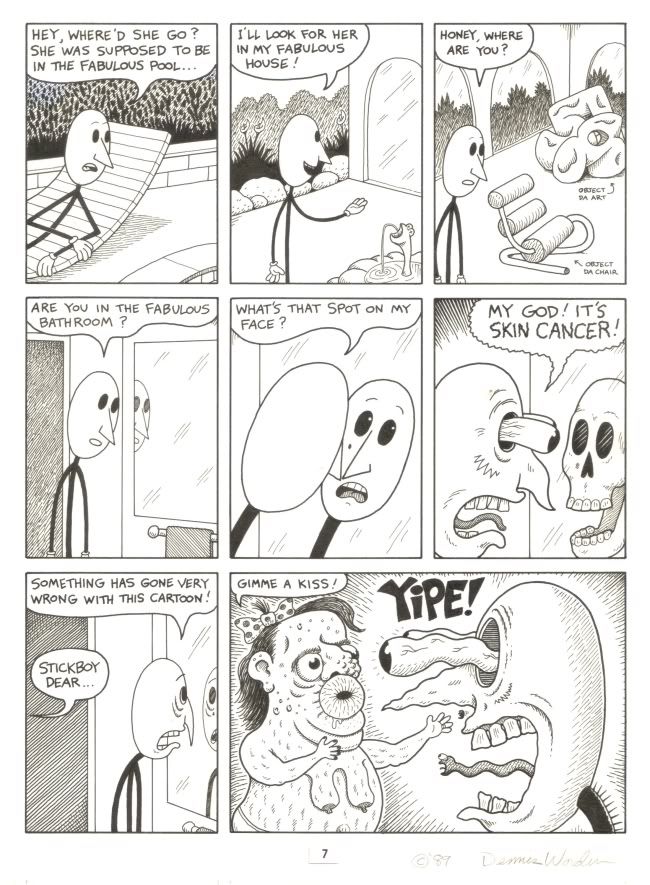

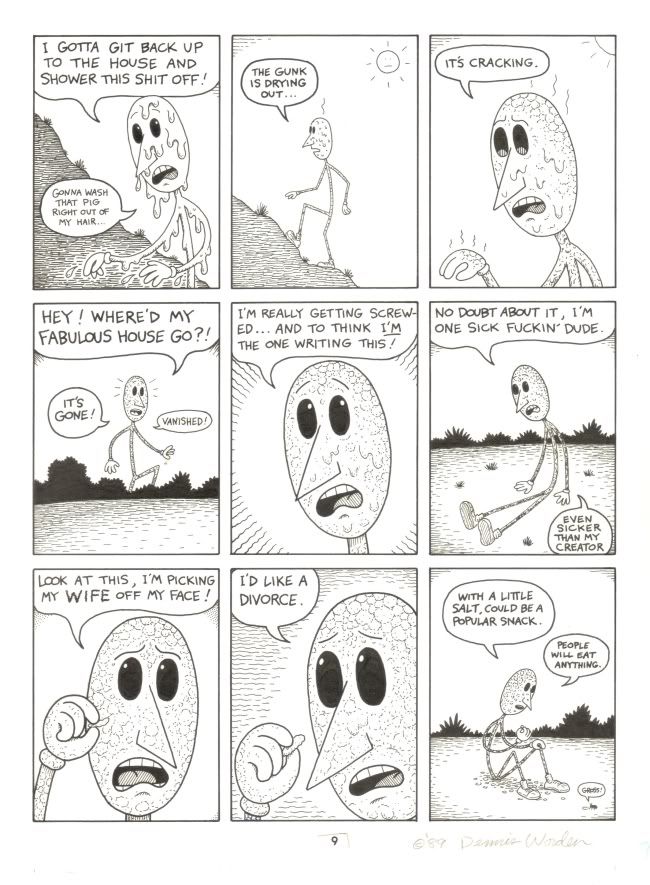

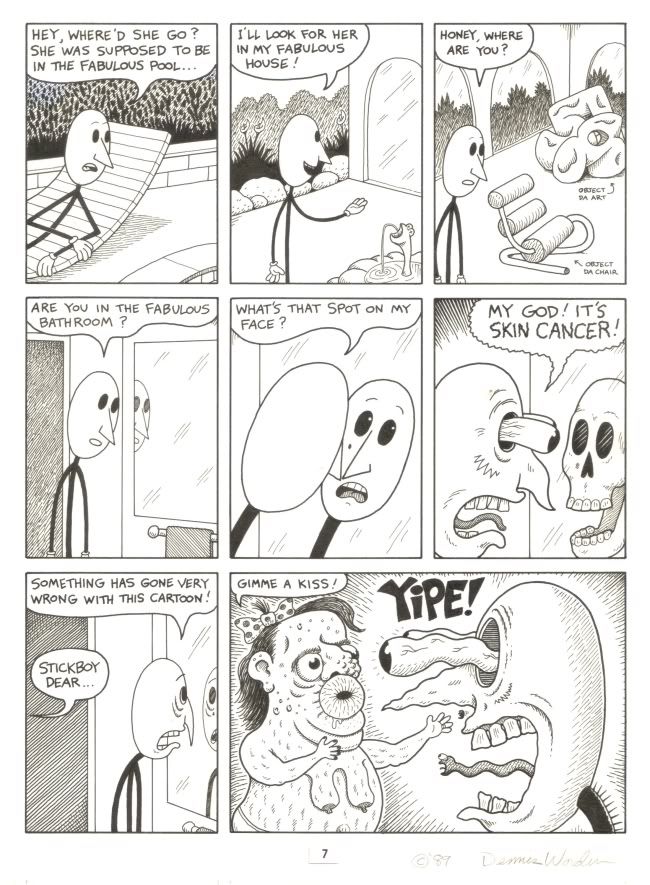

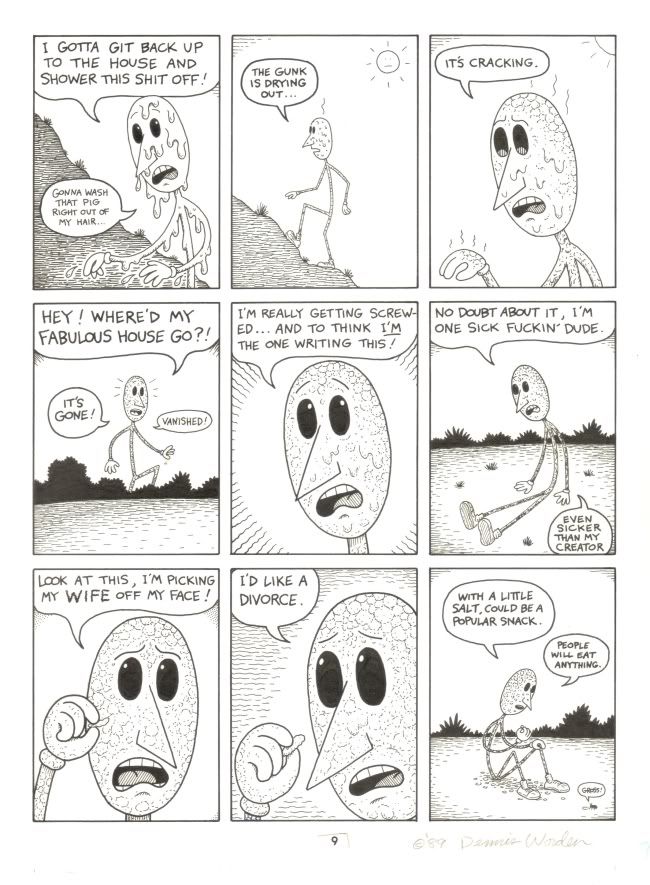

I bought three pages from Stickboy #3 (Fantagraphics, 1989). Worden drew them at pretty much their final printed size (8.5" x 11"), which is not typical (most comics are drawn larger than their final printed size). But Worden's art is so precise and clean (not to mention minimal) that they reproduce very well without having to be shrunk.

Cover of Stickboy #3

Worden, like Williams, had a powerful wise-ass punk attitude (as you will see in the pages I bought), but he also was unusually philosophical. (There is a self-mocking fan letter from Wayne White in Stickboy #3 praising Worden's philosophy.) Unlike most cartoonists Worden is an intellectual--a cranky, self-taught intellectual. I think Robert Crumb provided the path. Crumb is a universal cartoonist--within his vast work, every kind of self-examination takes place. Crumb is willing to tackle philosophical and religious ideas, and his own relationship to them, in a way that I think many cartoonists avoid out of a fear of looking foolish. Not Worden--he was quite willing to do the same and defend himself against attacks on his beliefs.

I love Worden's crisp minimal art, and always thought his comics were great. As far as I know, no one ever issued a book collection of his work. So if there is a publisher out there looking for an unusual project, I would say please publish a collection of the comics of Dennis Worden.

Dennis Worden, Stickboy #3, page 7, 1989

Dennis Worden, Stickboy #3, page 9, 1989

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck cover, 1985

J.R. Williams is an artist from Portland, Oregon. The pages here are from a minicomic he did in 1985 for Clay Geerdes Comix World. Clay Geerdes was an impresario of minicomics, publishing comics for many artists at the time.

What are minicomics? I guess the strictest definition would be that they were xeroxed comics printed on a piece of letter-sized paper folded over once then again to create a 4 1/4" x 5 1/2" 8-page booklet. But in general, minicomics has come to mean any self-published, micro-print-run comic (usually xeroxed). Minicomics arose with the rise of inexpensive and ubiquitous photocopiers in the 1970s. The people who drew them were amateur cartoonists inspired by the underground comics of the '60s. They formed their own networks through the mail, which in turn lead to an international movement of minicomics. (Minicomics can be seen as a subset of the zine movement of the same period. And many fans and practitioners connected to one another through the zine magazine, Factsheet Five.)

In the early 80s, minicomics were also called "newave" comics. (There is a massive collection of "Newave" comics coming out presently from Fantagraphics Books.) That's the term under which I first became aware of them, through the great comics critic Dale Luciano's mammoth survey of the "newave" scene that ran in several issues of The Comics Journal. Later, when I worked for Fantagraphics, I started writing a column about minicomics called "Minimalism" for The Comics Journal. I wrote it from 1992 to 1996, but it continues to this day, amazingly.

Many of the minicomics artists were really talented. They did minicomics for a variety of reasons, but for some of them, one reason was a lack of venues where they could get their work published commercially. The undergrounds pretty much died in the 1970s, and nothing took their place until the 80s. In the case of J.R. Williams, he found a home at Fantagraphics, where he had an ongoing series. But unlike many of his minicomics peers, he was a professional artist. When I first met him, he was working as an animator in Portland. He later moved up to Seattle to draw full time, and I later hired him to write a comic for me (Welcome to the Little Shop of Horrors).

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck page 1, 1985

Deadly Duck was published in the classic minicomics format. Williams' originals are "two up"--twice the size of the printed pages. His minimal drawing style is highly appropriate to the medium in which he is working, as is his sole idea in this story. In seven tiny pages, you can't put in much plot or characterization. But it's a good size for barbaric yawps like this.

J.R. Williams, Deadly Duck page 7, 1985

I was able to buy all eight pages directly from Williams. They are funny and drawn really well--perfect examples of what minicomics were all about in the 1980s.

Dennis Worden comes out of the same milieu as Williams. He was from the San Diego area. He started getting published in Weirdo, had comics published by Fantagraphics and other publishers, and now does paintings, which he will happily sell to you.

I bought three pages from Stickboy #3 (Fantagraphics, 1989). Worden drew them at pretty much their final printed size (8.5" x 11"), which is not typical (most comics are drawn larger than their final printed size). But Worden's art is so precise and clean (not to mention minimal) that they reproduce very well without having to be shrunk.

Cover of Stickboy #3

Worden, like Williams, had a powerful wise-ass punk attitude (as you will see in the pages I bought), but he also was unusually philosophical. (There is a self-mocking fan letter from Wayne White in Stickboy #3 praising Worden's philosophy.) Unlike most cartoonists Worden is an intellectual--a cranky, self-taught intellectual. I think Robert Crumb provided the path. Crumb is a universal cartoonist--within his vast work, every kind of self-examination takes place. Crumb is willing to tackle philosophical and religious ideas, and his own relationship to them, in a way that I think many cartoonists avoid out of a fear of looking foolish. Not Worden--he was quite willing to do the same and defend himself against attacks on his beliefs.

I love Worden's crisp minimal art, and always thought his comics were great. As far as I know, no one ever issued a book collection of his work. So if there is a publisher out there looking for an unusual project, I would say please publish a collection of the comics of Dennis Worden.

Dennis Worden, Stickboy #3, page 7, 1989

Dennis Worden, Stickboy #3, page 9, 1989

Labels:

art acquired,

comics,

Dennis Worden,

J.R. Williams,

Robert Crumb,

Wayne White

Thursday, December 31, 2009

Note on Footnotes in Gaza

Footnotes in Gaza by Joe Sacco

Sacco seems to have realized the futility of being a reporter who reports his news in the form of comics. Comics are too laborious, too time-consuming, to be an appropriate medium for reporting, which depends on at least a degree of immediacy. Hence this book is a history--he is investigating events from 1956. He shows the investigation as it unfolds, but already that time is itself in a past that is substantially different from today (he was researching this at the beginning of the Iraq War).

But one is forced to ask, why is this a comic book? People write excellent non-fiction books like this all the time (i.e., books where the author is part of the story, which combine history and personal stories. For example, I just read a supurb example of this genre, Methland.) Comics is Sacco's chosen medium, and he does it well, but prose seems better suited for this kind of book.

The answer may come be comparing Footnotes in Gaza to Robert Crumb's Genesis. It comes down to the faces. The stories of the massacres at Rafah and at Khan Younis and the story of Genesis share one important feature--a huge cast of characters, most not very important by themselves but important to the fabric of the story as a whole. In prose, a sea of names can overwhelm you. What Sacco and Crumb do is to give faces to the names that are unique and memorable. Of course, this requires consummate cartooning skills, which both artists have.

There are many things non-fiction prose can do with ease that are obviously difficult for Sacco to do. But he trades these for the ability to depict his subjects visually--their faces especially--which makes them memorable and gives them life.

Labels:

comics,

Joe Sacco,

Robert Crumb

Thursday, December 24, 2009

The Best Comics of 2009

Robert Boyd

I was going to do the top 10 comics of 2009, but I just couldn't limit myself to 10. So here are my top 15. Some big caveats going in. First, there are comics that came out this year that look really good that I haven't read yet. (For example, the new Joe Sacco book.) There are also probably comics that came out this year that are really good that I just don't know about. And finally, this list is personal and idiosyncratic. It is the list of a guy who values art comics and alternative comics far more than mainstream comics. My tastes were formed in the 80s and 90s, and I think that shows. I am someone who loves the comic strip form, especially as practiced before World War II. Also, I have found over the past few years that I haven't been reading many comic books. So the only comic book on this list is Multiforce (and calling it a comic book is kind of a stretch).So with that in mind, here we go!

The Top 15

1) Asterios Polyp by David Mazzucchelli. See my review here. A beautiful, rigorously structured, funny and moving book.

2) You Are There by Jean-Claude Forest and Jacques Tardi. See my review here. This is, like so many things on my list, actually quite an old work. But this edition is the first published in English.

3) Jack Survives by Jack Moriarity. This powerful body of work was mostly published in RAW in the 80s. Moriarty approaches these comics as a life-long painter, and this edition reproduces them as paintings, not as high-contrast line drawings, which is how they were originally printed. The result is mesmerizing without detracting from the stories. The stories are kind of abstractions of early 50s manhood. A guy in a hat with his family and his house... Brilliant pieces of minimalism created with a neo-expressionist painter's brush.

4) The Book of Genesis Illustrated by Robert Crumb. Awe-inspiring. In a way, Crumb has been too faithful. Using a very literal translation of the Bible by Robert Alter as his starting point, he tries to keep interpretation to a minimum. One result is that the comic form is compromised in at least one obvious way. The Bible will have passages that read, "He said, Blah blah blah" In the Bible, there are no freestanding quotations of spoken words. So in a panel where Crumb is depicting someone speakings, there is always a little caption preceeding the word balloon that says something like, "And then Jacob said" This is really weird. What these captions are saying is being shown through the use of the visual device of the word balloon. This was just one of the awkward things that comes from including every word of a prose work in a different medium (comics). Of course, his artistry makes up for a lot of awkwardness. You can stare at this book forever. One aspect of Genesis that is really boring is the listing of names--the "begats." But Crumb, drawing all these hundreds of faces, turns that weakness of the text into an overwhelming strength--each face, so individual, implies a story, a life. It's a beautiful piece of work.

5) George Sprott (1894-1975) by Seth. This ran in the New York Times Magazine, and for this book, Seth has added some incidental art (spectacular, of course--it includes cardboard models of the buildings from the story) and two short recollections of Sprott's boyhood and youth. Seth uses a technique that I think really works better for him than telling a story as a straight narrative. Each page is its own little episode--set in its own time, focusing on a particular person. The sum of these episodes is George Sprott's awful life--an asshole whose career is an extended riff on one minor achievement of his young manhood. It is amazing how compelling this nasty character is!

6) The Complete Little Orphan Annie, vol. 3 by Harold Gray. See my review here. An unusually powerful melodrama from the depths of the Depression.

7) Popeye, vol. 4 by E.C. Segar. This is the volume with the great "Plunder Island" sequence, which introduced many of us to the genius of Segar when it was reproduced in the Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics. But the whole of this book is top-notch, Segar at his greatest. Includes a lengthy and hilarious sequence of Popeye in drag, romancing a baddie.

8) Journey, vol 2 by William Messner-Loebs. An underappreciated classic from the 80s, published in the first great flush of "independent comics" that brought us classics like Love & Rockets and Yummy Fur. MacAlistaire and the failed poet Elmer Alyn Craft (who was introduced in the first volume) are stranded in the barely there settlement of New Hope for a winter. This village is claustrophobic and full of horrible secrets. Craft is obsessed with finding them--MacAlistaire is interested only insofar as it will help him survive the winter. Messner-Loebs' drawing has lost what little polish it exhibited in the first volume. It becomes ragged and urgent here, fitting the psychologically intense and unsettling story.

9) Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, vol. 8. This is a particularly rich volume. Gould made a decision to not send Dick Tracy to war, but the war pops up. Pruneface is an enemy agent that Tracy must shut down. His most terrifying villain in this volume, however, is Mrs. Pruneface, a hulking skullfaced woman seeking revenge for her man's death. And of Tracy's iconic villains, Flattop rounds out this volume (and we meet Vitamin Flintheart, who will be a recurring character). The art is, as always, excellent.

10) Multiforce by Mat Brinkman. I've read a lot of these strips here and there, and only now realize that they all sort of fit together.This oversized, saddle-stitched book brings the whole saga together. And "saga" is the right word. Multiforce is simultaneously the kind of epic a ten-year-old boy would conceive of and at the same time the kind of art that a sophisticated product of elite art education might create. The work slithers between these two poles trickily. And Brinkman never fails to be amusing. This may remind some people of Trondheim and Sfarr's Dungeon books, which are clever and funny, but frankly feel contrived next to Multiforce. Great, weird art and storytelling.

11) Cecil and Jordon in New York by Gabrielle Bell. Very good--Bell's art is outstanding in a non-showy, matter-of-fact way. In some stories, she never shows you someone's face in a close-up, and in some of her autobiographical stories, almost ever figure is drawn full-figure--in other words you see their feet and heads in every panel they are in. The distance from the observer and the characters is pretty large. It's a weird way to tell an autobiographical story--its as if the author was pretending not to know what was going through the mind of the character. It creates an interesting contradiction, as if Bell were alienated from her earlier self. That feeling carries through in her fiction stories too. The characters seem to feel disconnected from their lives, even as they have what (on the surface) seem like pretty engaging experiences. Her characters never get happy, which can be kind of a downer. The title story even features a character who would be happier as a chair--she'd feel useful that way, and not have to struggle the way she did when she was a full-time girl.

12) Everyone Is Stupid Except For Me by Peter Bagge. This collection has been a long time coming. Peter Bagge has been doing these reportorial strips for Reason for years, and before that he did similar strips for the late, lamented web magazine Suck. His reporting is infused with his own style of humor, which will resonate with fans of Hate (like me). But what is different is that he is actually reporting here--going out, covering events, talking to participants, doing research, etc. Satirical reporting may have been around forever, but in modern times, Spy was the first big practitioner of it. Spy spawned a host of mostly online followers--Suck, of course, and nowadays websites like Gawker and Wonkette. But those sites are mostly picking up news and adding their own snarky spin. Like the writers for Spy, Bagge is going out and doing the digging himself, and like the great magazine reporters of the '60s and '70s, he puts himself in the stories. Most of this work is in service of Bagge's (and Reason's) libertarian beliefs. Don't expect him to be "fair"--he has a point of view and he is going to hammer it home. But he is a humorist first, so he is constantly mocking his own side (if they are mockable) as well as the protagonists of his stories. But if you are not a libertarian, you'll find yourself muttering "That's outrageous!" at many of Bagge's broader caricatures of liberals or conservatives. Get past that! These strips are very, very funny, and if they force you to work harder to defend your point of view against Bagge's arguments, is that bad?

13) You’ll Never Know book 1: A Good and Decent Man by Carol Tyler. Great but somewhat confused biography/memoir. Carol Tyler is attempting to tell the story of her dad in World War II. She is faced with a problem, though. Tyler's dad doesn't want to talk about a certain part of it--his time in Italy. We are given hint that he saw a literal "river of blood," and the trauma has kept him silent for decades. Even his wife doesn't know. Tyler herself is going through her own stuff--an absent husband, a beautiful teenage daughter, life. Tyler is better at short pieces, where she can focus. This is a glorious mess, but a moving and beautiful one. The format is unusual too. Tyler uses the horizontal format of a scrapbook. Also, for some reason, the whole thing is not being told in one volume. I suppose I will wait long frustrating months (and years?) for the next volume.

14) Map of My Heart by John Porcellino. I think this could have been better edited. As it is, they just reprinted whole issues of King Kat, including letters to Porcellino. This approach, however, feels consistent with the basic vibe of King Cat. The stories are slight, filled with simple joy or being alive or with small regrets. In between the stories, there are journal entries and annotations where Porcellino tells us about the arc of his marriage, his sense of failure at getting divorced, his mysterious chronic illness. etc. These are almost never the subjects of his comics. At least not directly. His work is oblique that way, but never obscure. On the contrary, emotion is right on the surface. Lots of very moving stories here.

15) Nine Ways to Disappear by Lilly Carre. This is a collection of witty little stories. Some have the flavor of modern fairy tales ("The Pearl"), and all of them have an other-worldly quality. She uses a primitive panel progression--one panel per page, like the old woodcut guys (Lynd Ward, Franz Masereel). To emphasize the separateness of each panel, each one has a decorative border (recalling Lynda Barry, perhaps). But the stories flow perfectly well, and doing it this way made me linger a bit over each panel. Which is nice, because they are lovely. My favorite story is "Wide Eyes", the story of a man who falls in love with a woman with widely-spaced eyes, but feeling oppressed by them, finds he can hide from her by standing very close to her face, between her eyes and apparently outside her field of vision. My favorite character is the only recurring one, a lonely storm grate.

(A little side note--of the top 15 books, four were published by Fantagraphics, three by Drawn & Quarterly, three by IDW, and one each by Norton, Buenaventura Press, Pantheon, Little Otsu, and Picturebox.)

Honorable mention

Here are some other 2009 comics I liked.

The Best American Comics 2009 edited by Charles Burns

The Cartoon History of the Modern World vol. 2 by Larry Gonick

The Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, vol. 7

The Complete Little Orphan Annie, vol. 2 by Harold Gray

A Drifiting Life by Yoshiharu Tatsumi

Ho! by Ivan Brunetti

Humbug by Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Davis, Al Jaffee, Arnold Roth, Will Elder, etc.

Key Moments from the History of Comics by François Ayroles

Low Moon by Jason

Masterpiece Comics by R. Sikoryak

A Mess of Everything by Miss Lasko-Gross

The Perry Bible Fellowship Almanack by Nicholas Gurewitch

Pim & Francie by Al Columbia

Stitches by David Small

Terry and the Pirates, vol.6 by Milton Caniff

West Coast Blues by Jean-Patrick Manchette and Jacques Tardi

Art Books

I also want to acknowledge a few great books that came out in 2009 that are more "art books" than comics, but which contain comics and/or have a strong relationship to comics. All of these books are really beautiful and quite worth investing in a big new coffee table on which to display them.

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics

The Art of Tony Millionaire

Hot Potatoe by Marc Bell

Wayne White: Maybe Now I'll Get the Respect I So Richly Deserve

I was going to do the top 10 comics of 2009, but I just couldn't limit myself to 10. So here are my top 15. Some big caveats going in. First, there are comics that came out this year that look really good that I haven't read yet. (For example, the new Joe Sacco book.) There are also probably comics that came out this year that are really good that I just don't know about. And finally, this list is personal and idiosyncratic. It is the list of a guy who values art comics and alternative comics far more than mainstream comics. My tastes were formed in the 80s and 90s, and I think that shows. I am someone who loves the comic strip form, especially as practiced before World War II. Also, I have found over the past few years that I haven't been reading many comic books. So the only comic book on this list is Multiforce (and calling it a comic book is kind of a stretch).So with that in mind, here we go!

The Top 15

1) Asterios Polyp by David Mazzucchelli. See my review here. A beautiful, rigorously structured, funny and moving book.

2) You Are There by Jean-Claude Forest and Jacques Tardi. See my review here. This is, like so many things on my list, actually quite an old work. But this edition is the first published in English.

3) Jack Survives by Jack Moriarity. This powerful body of work was mostly published in RAW in the 80s. Moriarty approaches these comics as a life-long painter, and this edition reproduces them as paintings, not as high-contrast line drawings, which is how they were originally printed. The result is mesmerizing without detracting from the stories. The stories are kind of abstractions of early 50s manhood. A guy in a hat with his family and his house... Brilliant pieces of minimalism created with a neo-expressionist painter's brush.

4) The Book of Genesis Illustrated by Robert Crumb. Awe-inspiring. In a way, Crumb has been too faithful. Using a very literal translation of the Bible by Robert Alter as his starting point, he tries to keep interpretation to a minimum. One result is that the comic form is compromised in at least one obvious way. The Bible will have passages that read, "He said, Blah blah blah" In the Bible, there are no freestanding quotations of spoken words. So in a panel where Crumb is depicting someone speakings, there is always a little caption preceeding the word balloon that says something like, "And then Jacob said" This is really weird. What these captions are saying is being shown through the use of the visual device of the word balloon. This was just one of the awkward things that comes from including every word of a prose work in a different medium (comics). Of course, his artistry makes up for a lot of awkwardness. You can stare at this book forever. One aspect of Genesis that is really boring is the listing of names--the "begats." But Crumb, drawing all these hundreds of faces, turns that weakness of the text into an overwhelming strength--each face, so individual, implies a story, a life. It's a beautiful piece of work.

5) George Sprott (1894-1975) by Seth. This ran in the New York Times Magazine, and for this book, Seth has added some incidental art (spectacular, of course--it includes cardboard models of the buildings from the story) and two short recollections of Sprott's boyhood and youth. Seth uses a technique that I think really works better for him than telling a story as a straight narrative. Each page is its own little episode--set in its own time, focusing on a particular person. The sum of these episodes is George Sprott's awful life--an asshole whose career is an extended riff on one minor achievement of his young manhood. It is amazing how compelling this nasty character is!

6) The Complete Little Orphan Annie, vol. 3 by Harold Gray. See my review here. An unusually powerful melodrama from the depths of the Depression.

7) Popeye, vol. 4 by E.C. Segar. This is the volume with the great "Plunder Island" sequence, which introduced many of us to the genius of Segar when it was reproduced in the Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics. But the whole of this book is top-notch, Segar at his greatest. Includes a lengthy and hilarious sequence of Popeye in drag, romancing a baddie.

8) Journey, vol 2 by William Messner-Loebs. An underappreciated classic from the 80s, published in the first great flush of "independent comics" that brought us classics like Love & Rockets and Yummy Fur. MacAlistaire and the failed poet Elmer Alyn Craft (who was introduced in the first volume) are stranded in the barely there settlement of New Hope for a winter. This village is claustrophobic and full of horrible secrets. Craft is obsessed with finding them--MacAlistaire is interested only insofar as it will help him survive the winter. Messner-Loebs' drawing has lost what little polish it exhibited in the first volume. It becomes ragged and urgent here, fitting the psychologically intense and unsettling story.

9) Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, vol. 8. This is a particularly rich volume. Gould made a decision to not send Dick Tracy to war, but the war pops up. Pruneface is an enemy agent that Tracy must shut down. His most terrifying villain in this volume, however, is Mrs. Pruneface, a hulking skullfaced woman seeking revenge for her man's death. And of Tracy's iconic villains, Flattop rounds out this volume (and we meet Vitamin Flintheart, who will be a recurring character). The art is, as always, excellent.

10) Multiforce by Mat Brinkman. I've read a lot of these strips here and there, and only now realize that they all sort of fit together.This oversized, saddle-stitched book brings the whole saga together. And "saga" is the right word. Multiforce is simultaneously the kind of epic a ten-year-old boy would conceive of and at the same time the kind of art that a sophisticated product of elite art education might create. The work slithers between these two poles trickily. And Brinkman never fails to be amusing. This may remind some people of Trondheim and Sfarr's Dungeon books, which are clever and funny, but frankly feel contrived next to Multiforce. Great, weird art and storytelling.

11) Cecil and Jordon in New York by Gabrielle Bell. Very good--Bell's art is outstanding in a non-showy, matter-of-fact way. In some stories, she never shows you someone's face in a close-up, and in some of her autobiographical stories, almost ever figure is drawn full-figure--in other words you see their feet and heads in every panel they are in. The distance from the observer and the characters is pretty large. It's a weird way to tell an autobiographical story--its as if the author was pretending not to know what was going through the mind of the character. It creates an interesting contradiction, as if Bell were alienated from her earlier self. That feeling carries through in her fiction stories too. The characters seem to feel disconnected from their lives, even as they have what (on the surface) seem like pretty engaging experiences. Her characters never get happy, which can be kind of a downer. The title story even features a character who would be happier as a chair--she'd feel useful that way, and not have to struggle the way she did when she was a full-time girl.

12) Everyone Is Stupid Except For Me by Peter Bagge. This collection has been a long time coming. Peter Bagge has been doing these reportorial strips for Reason for years, and before that he did similar strips for the late, lamented web magazine Suck. His reporting is infused with his own style of humor, which will resonate with fans of Hate (like me). But what is different is that he is actually reporting here--going out, covering events, talking to participants, doing research, etc. Satirical reporting may have been around forever, but in modern times, Spy was the first big practitioner of it. Spy spawned a host of mostly online followers--Suck, of course, and nowadays websites like Gawker and Wonkette. But those sites are mostly picking up news and adding their own snarky spin. Like the writers for Spy, Bagge is going out and doing the digging himself, and like the great magazine reporters of the '60s and '70s, he puts himself in the stories. Most of this work is in service of Bagge's (and Reason's) libertarian beliefs. Don't expect him to be "fair"--he has a point of view and he is going to hammer it home. But he is a humorist first, so he is constantly mocking his own side (if they are mockable) as well as the protagonists of his stories. But if you are not a libertarian, you'll find yourself muttering "That's outrageous!" at many of Bagge's broader caricatures of liberals or conservatives. Get past that! These strips are very, very funny, and if they force you to work harder to defend your point of view against Bagge's arguments, is that bad?

13) You’ll Never Know book 1: A Good and Decent Man by Carol Tyler. Great but somewhat confused biography/memoir. Carol Tyler is attempting to tell the story of her dad in World War II. She is faced with a problem, though. Tyler's dad doesn't want to talk about a certain part of it--his time in Italy. We are given hint that he saw a literal "river of blood," and the trauma has kept him silent for decades. Even his wife doesn't know. Tyler herself is going through her own stuff--an absent husband, a beautiful teenage daughter, life. Tyler is better at short pieces, where she can focus. This is a glorious mess, but a moving and beautiful one. The format is unusual too. Tyler uses the horizontal format of a scrapbook. Also, for some reason, the whole thing is not being told in one volume. I suppose I will wait long frustrating months (and years?) for the next volume.

14) Map of My Heart by John Porcellino. I think this could have been better edited. As it is, they just reprinted whole issues of King Kat, including letters to Porcellino. This approach, however, feels consistent with the basic vibe of King Cat. The stories are slight, filled with simple joy or being alive or with small regrets. In between the stories, there are journal entries and annotations where Porcellino tells us about the arc of his marriage, his sense of failure at getting divorced, his mysterious chronic illness. etc. These are almost never the subjects of his comics. At least not directly. His work is oblique that way, but never obscure. On the contrary, emotion is right on the surface. Lots of very moving stories here.

15) Nine Ways to Disappear by Lilly Carre. This is a collection of witty little stories. Some have the flavor of modern fairy tales ("The Pearl"), and all of them have an other-worldly quality. She uses a primitive panel progression--one panel per page, like the old woodcut guys (Lynd Ward, Franz Masereel). To emphasize the separateness of each panel, each one has a decorative border (recalling Lynda Barry, perhaps). But the stories flow perfectly well, and doing it this way made me linger a bit over each panel. Which is nice, because they are lovely. My favorite story is "Wide Eyes", the story of a man who falls in love with a woman with widely-spaced eyes, but feeling oppressed by them, finds he can hide from her by standing very close to her face, between her eyes and apparently outside her field of vision. My favorite character is the only recurring one, a lonely storm grate.

(A little side note--of the top 15 books, four were published by Fantagraphics, three by Drawn & Quarterly, three by IDW, and one each by Norton, Buenaventura Press, Pantheon, Little Otsu, and Picturebox.)

Honorable mention

Here are some other 2009 comics I liked.

The Best American Comics 2009 edited by Charles Burns

The Cartoon History of the Modern World vol. 2 by Larry Gonick

The Complete Chester Gould's Dick Tracy, vol. 7

The Complete Little Orphan Annie, vol. 2 by Harold Gray

A Drifiting Life by Yoshiharu Tatsumi

Ho! by Ivan Brunetti

Humbug by Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Davis, Al Jaffee, Arnold Roth, Will Elder, etc.

Key Moments from the History of Comics by François Ayroles

Low Moon by Jason

Masterpiece Comics by R. Sikoryak

A Mess of Everything by Miss Lasko-Gross

The Perry Bible Fellowship Almanack by Nicholas Gurewitch

Pim & Francie by Al Columbia

Stitches by David Small

Terry and the Pirates, vol.6 by Milton Caniff

West Coast Blues by Jean-Patrick Manchette and Jacques Tardi

Art Books

I also want to acknowledge a few great books that came out in 2009 that are more "art books" than comics, but which contain comics and/or have a strong relationship to comics. All of these books are really beautiful and quite worth investing in a big new coffee table on which to display them.

The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics

The Art of Tony Millionaire

Hot Potatoe by Marc Bell

Wayne White: Maybe Now I'll Get the Respect I So Richly Deserve

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)