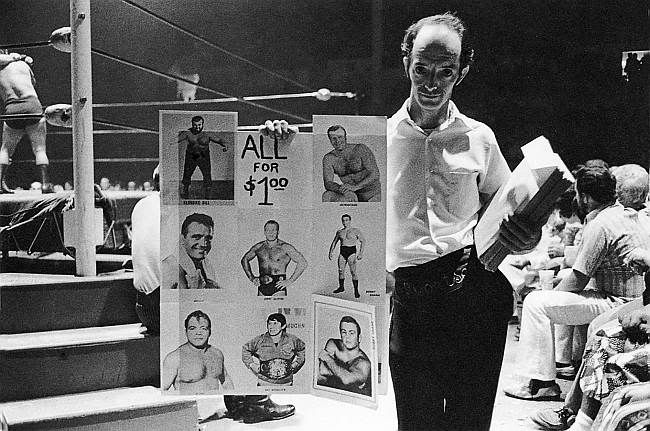

Geoff Winningham, Houston Coliseum 1971, vintage gelatin silver print (1975) from a 35 mm negative, image size 12" x 18", uneditioned, from Friday Night at the Coliseum (1971)

Geoff Winningham has been taking photos of Mexico and Texas for decades. He started teaching at Rice in 1969 and is still a photography professor there. I took classes from him when I was an undergrad in the 80s. He radiated a love for photography then, and comes through in this show, which collects work from various points in his career, including this early photo, Houston Coliseum 1971. The Sam Houston Coliseum was a municipal sports arena downtown. This is where folks went to see wrestling, than as now a downmarket form of entertainment (the Coliseum was torn down in 1998 and replaced with the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts, a much more upmarket entertainment venue). I saw many rock concerts at the Coliseum as a teenager and young adult, but I never saw wrestling there. But Winningham captured it--in this photo with the contrapposto stance, the shadowed face. the tiny wrestler up to the left--it feels almost surreal rather than documentary.

Geoff Winningham, Leadville, Colorado #2 1994, carbon pigment print (2012) on brushed aluminum from a 4x5 film negative, 24" x 30", #1 in an edition of 3 with 1 artist's proof

Leadville Colorado #2 may be my favorite photo in the show. He photographed this in an abandoned barn in Leadville, Colorado. The barn was locked, but there was enough space under the door that he could crawl in with his 4x5 view camera. Nothing in the barn appeared to be any newer than 1943 (he took this photo in 1994). The walls were covered with tattered bit of paper. The barn was dark--Winningham says that to get this picture (and the three others from the same barn that are in the show), he had to expose the negatives for 30 minutes.

The result is powerful. It will remind one of the paintings of W.M. Harnett and especially John Frederick Peto. They both painted flat surfaces with stuff attached to them--19th century bulletin boards in a sense. They both dealt with memory and identity, as defined by images and words. And this is the name of Winningham's show: Words and Pictures: 1971 - 2012.We don't know who pinned all these items to the wall in Leadville, but close examination of the photo lets us get to know that person. And the decayed condition reminds us that this person, who over time covered the walls with images and words that he considered important, is long dead. Memory is always in a battle with death. Peto frequently included a small photo of Lincoln in his paintings of bulletin boards. In the story "Metamophosis" by David Eagleman, it is explained that after you die, you go to an afterlife. But you can (and will) die again, in the "moment, sometime in the future, when your name is spoken for the last time." Somehow, this decaying collage of pinned up detritus seems, in Winningham's photo, a struggle against oblivion. We may not know his name, but we feel we know him in some way--all because Winningham crawled under a door and spent several hours photographing in a barn.

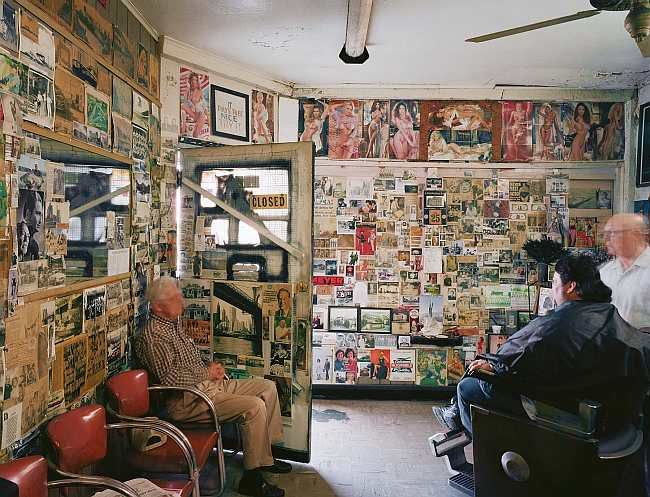

Geoff Winningham, Jerdy's Barber Shop, Port Arthur, Texas 2004, Fuji Archive print (2007) from a 4x5 film negative, image size 15.25" x 19.75", uneditioned

Again in Jerdy's Barber Shop we have the idea of things pinned to a wall that reflect (or create) identity--in this case, the identity of a place. This is the barber shop as a place for men (see Stuart Davis's Men Without Women). The Playboy centerfolds on the wall speak to that. What strikes me about both this photo and the previous one is that the person who owns the space (presumably Jerdy in this case) is a collector of images. This is something I relate to, and presumably something Winningham relates to as well. In fact, collectors of images include compulsive wall-coverers like Jerdy, photographers like Winningham, art critics like me, art collectors, and people with Pinterest accounts. We may not have a lot in common otherwise, but this image-gathering compulsion is an important part of us. Unfortunately, we can't go see Jerdy's collection. Winningham writes, "Jerdy Fontenot's unforgettable barber shop was destroyed by Hurricane Rite, the year after I took this photo."

Geoff Winningham, Transition 2008, archival inkjet (2008) print on German etching paper

Transition 2008 has the same density as Jerdy's Barber Shop, but feels more modern--or postmodern. When I was a student, I thought of Winningham as a documentary photographer who made compelling images of what he could see through his viewfinder out in the world. I didn't see him as postmodern. His work was close to the subject, pretty much unmediated. It was unposed. It was often about finding the perfect image, like Cartier-Bresson. But this selection has me thinking that Winningham was a postmodernist all along. This "photo" is a good example. Transitions consist of about 600 photographic images, arranged chronologically, of Obama's inauguration. he took the photos off a big screen TV and then collaged them. So unlike any classical notion of photography (one moment in time, seen by the photographer, captured on film) we have an event that took many hours, photographs of other images, as seen by other cameramen.

But this is true of most of the work in this show to some extent. So much of it consists of photos of someone else's images or words, or someone else's vernacular curation of images. It has really made me reevaluate Winningham as a photographer. His work, which I always admired, seems so much richer after seeing this exhibit.

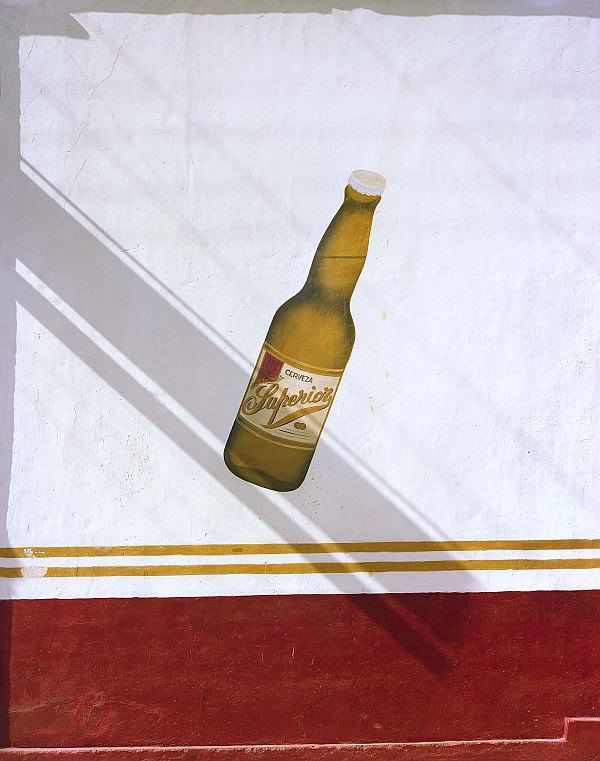

Geoff Winningham, Chiapas, Mexico 1983, archival inkjet print on Moab Enrada rag paper from an 8" x 10" film negative, image size 11.75" x 15", #1 print of an edition of 5

Chiapas, Mexico 1983 stands out for its simple composition. Unlike many of the pieces above, there isn't an all-over composition nor is the image dense with information. With the intersecting diagonals and horizontal elements, it comes across as a minimalist design. But the concerns of the other pieces in the show are still present. We get the written word--"Superior" and the sense of photographing someone else's art. This image is, in fact, hand-painted on the wall.

There are so many great FotoFest exhibits up now or opening in the next couple of weeks. Many of them are excellent. It would be difficult for any one person to see them all (even me). But if you're reading this, go see Words and Pictures: Photographs 1971 - 2012 at Koelsch Gallery. It's a moving, eye-opening show.