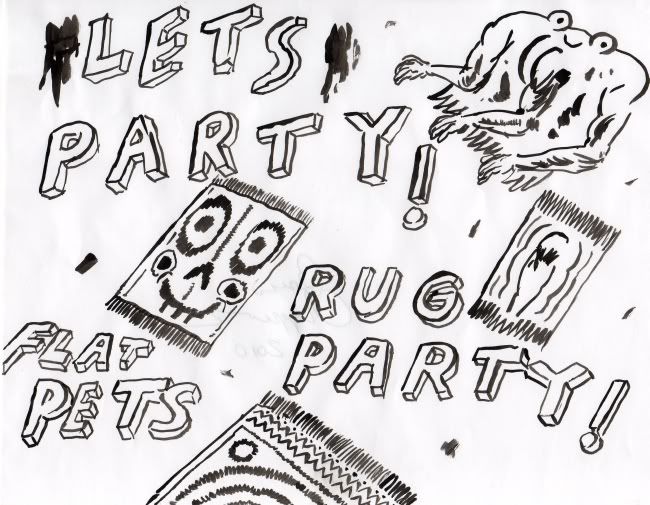

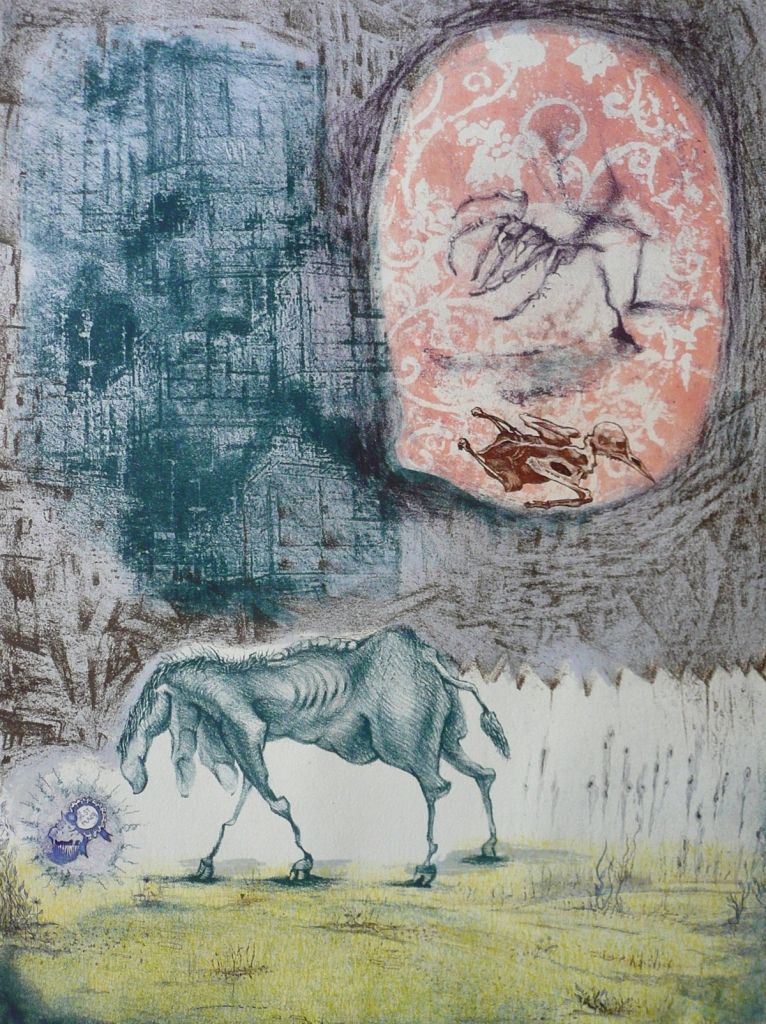

At first glance it seems like a spastic horse, until you notice fingers on its neck and that bony dinosaur back ridge. Distant architecture with barely discernible towers and turrets bespeak medieval Europe, but a flying bird skeleton indicates something more hellish. I’m looking at Xenia Fedorchenko’s No Free Lunch, a stone litho and intaglio print in the group exhibition Heavy Hitters at Peveto through July 7.

Xenia Fedorchenko, No Free Lunch, 2012, lithography & intaglio, 15 1/4 x 20 1/4 inches

I first encountered Fedorchenko’s art in 2007 when she exhibited a copper plate etching of a severely disfigured nude in Lawndale’s Big Show. Its knee warts and sagging tits made me want to meet the artist who turned out to be Russian born, and who the year before had moved from the east coast to Beaumont to teach at Lamar University. With Untitled at Lawndale, Fedorchenko was making her Houston exhibition debut.

The Lawndale print was part of an on ongoing series of grotesque nudes meant to penetrate our excessive focus on outer appearance. Face lifts and other surface concerns, Fedorchenko believes, distance us from our corporeality. We “exist in a body without embodying it,” she told me.

The past colors her perspective. Fedorchenko lived in Moscow before the collapse of the Soviet Union, where there was scarcity, contrasted to American abundance. Arguably, people who experience waiting in line for necessities are probably less concerned with cellulite and perfect teeth.

I am recalling a nude she printed a few years back at Texas Collaborative, Dan Allison’s Houston print shop. It had a basketball shaped stomach and a painfully tiny penis atop wrinkly thin legs. Despite these afflictions, it wore a self satisfied smirk.

As previously mentioned, in No Free Lunch a bird carcass flies above the dinosaur “horse.” This motif of a flying “demon” is a compositional element shared with many of the nudes, which also include small flying figures. The flying demon it turns out is derived from devils who torture the damned in medieval depictions of Hell, particularly from the distinct current of Northern European medieval expressionism that includes the beaked, horned and scaly devils by Martin Schongauer who attack poor Saint Anthony. The flying dead bird’s thorny reptilian features relate it to Schongauer’s devils, and also to Matthias Grunewald’s devils with bird-like features. Grunewald also painted scaly dragon devils, some covered with mucous and excrement. Those who rape the wicked while they fly are very similar to Xenia’s flying caressing nudes.

In 2007 I noticed in one of her prints a fish emerging from a nude’s vagina, which directly quotes Bosch, who seems near hysteria in his dedication to helping sinners understand how horrible Hell is. In Bosch’s imagination torture can be even more hideous than a fish in your crotch. Many of his wicked have sharp objects up their butts. It was unnecessary to ask Fedorchenko if she looked closely at Bosch because her print included letterpress text of his writing, “a false paradise, sinful and demonic, the inhabitants of which would be damned.”

Fedorchenko’s treatment of skin also references medieval narrations of Hell in which devils are portrayed with rotting skin and the miserable sinners have diseased skin. Grunewald painted a corpse with syphilitic lesions that are art historically notorious. Fedorchenko’s blemished and pocked flesh, like to the putrefied rib cage on her horse, nods in that direction.

Not having spoken to Fedorchenko since 2007, I contacted her to hear the latest. Fedorchenko replied from Florence, it’s her semester break, said she could better reply when she arrived in Venice, and then wrote from Venice. She continues her teaching schedule, recently exhibited art in Saint Louis Missouri, and spends quite a bit of time giving printing demonstrations at other universities, recently at a university in California.

What’s with the horse? “The horse, a beast of labor,” she said, “symbolizes the average citizen, out of shape, overworked and tired.” According to Fedorchenko its small head and weird body indicate it’s confused, unsure of its surroundings and possibly defeated. The imposing disorganized city threatens. “Occasionally life presents the horse-being with a seemingly wonderful opportunity, the award-winning cup-cake/muffin thing, but still the being hesitates to seize it as a bird-killing monster may be lurking.”

“There’s no free lunch,” she wrote from Venice.