I included three art things that I saw in 2016 in Houston and vicinity in Glasstire's "Best of 2016" list. To narrow it down to those three, I had to start from a larger list. It was hard to choose the final three--indeed, my top three changed several times.

In the Glasstire list, I included

Various works by JooYoung Choi in various Houston venues

Pat Palermo's Galveston Drawing Diary by Pat Palermo

The Color of Being/ El Color del Ser: Dorothy Hood (1918-2000) at the Art Museum of South Texas

The Glasstire list has a lot of good exhibits that made my long list. I don't want to repeat their work, so here is a brief list of events I liked that Glasstire included in their long list:

Andy Campbell, PoMo Houston Bus Tour

Jamal Cyrus, Untitled, 2010

Joey Fauerso, A Soft Opening at David Shelton, Houston

As Essential as Dreams: Self-Taught Art from the Collection of Stephanie and John Smither, The Menil Collection

And here are the some more that I liked that did not make the Glasstire list:

Holy Barbarians: Beat Culture on the West Coast at the Menil featuring John Altoon, Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner, Jay DeFeo, George Herms and Edward Keinholz.

Part of the reason I was so intrigued by this inventory exhibit was because I recently read Welcome to Painterland: Bruce Conner and the Rat Bastard Protective Association

George Herms, Greet the Circus with a Smile, 1961, mannequin torso, salvaged wood, feathers, tar, cement, cloth, plant material, paint, crayon, ink, paper, photographs, metal, plastic, glass, cord, mirror, electrical light fixture, and phonograph tone-arm, 68 × 28 1/2 × 20 in.

The odd men out in this collection are Kienholz--who really was a beatnik of sorts but much more ambitious than DeFeo or Berman--and Altoon, who lived like a beatnik but never was, as far as I can determine, associated with the movement.

In addition to showing a bunch of extremely choice artworks, it also shows several issues of Wallace Berman's early poetry and art publication Semina. Each issue was printed with letterpress on unbound slips of paper. It was truly a 'zine avant la lettre.

The exhibit will be up until March 12, 2017.

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (cross), 1953, wood, cloth, plaster, synthetic resin, and nails, 28 1/2 × 16 1/2 × 4 in.

Earl Staley designs for Faust at the Houston Grand Opera. These designs (sets, backdrops and costumes) were originally created by Staley in 1985. He was traveling in Italy and Greece at the time when the HGO contacted him. All his work for it was done abroad. The painted scrims are done in Staley's expressionist style which works wonderfully for this old warhorse. Every few years these costumes and sets are pulled out of storage and performed somewhere--for example, they were used for an Atlanta production in 2014.

The photo below is of the scrim you see before the opening and between acts. It looks a bit washed out compared to the real thing--it's hard to photograph, apparently. The sets had intense color and deep shadows. This infernal scrim was a remarkable depiction of hell and Satan.

Earl Staley, scrim in the original 1985 production of Faust (courtesy of Earl Staley)

Sharp by Havel+Ruck in Sharpstown.

I wrote about this work in Glasstire. If you haven't seen it, they're tearing it down January 1. (Might be worth a trip to Sharpstown to see it town down.)

Sharp by Havel+Ruck

Faith Wilding at UHCL.

I wrote about this exhibit in Glasstire. Nice show in an unexpected location.

Faith Wilding, Flow, 2010-2016, chemistry vessels, cheesecloth, water, ink

Statements at MFAH featuring Mequitta Ahuja, Nick Cave, Glenn Ligon, Kara Walker, John Biggers, Elizabeth Catlett, Melvin Edwards, Loretta Pettway, Louise Ozell Martin, Gordon Parks, Ernest C. Withers, Lonnie Holley, Jean Lacy, Thornton Dial, Sr., Jesse Lott, Dawolu Jabari Anderson, Michael Ray Charles, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Robert Pruitt, Mark Bradford, and Tierney Malone. This inventory exhibit got a certain amount of criticism for not having a very interesting curatorial idea. The only thing the artists necessarily had in common was that they were African American. Sure, you'd like an exhibition to have a stronger theme than "here's a bunch of stuff we had in storage by African American artists", but the pieces they displayed were really exciting. The show might not have been greater than the sum of its parts, but did it need to be when the parts were this good?

Dawolu Jabari Anderson, Twinkle Twinkle Little Tar, 2009, 72 x 48 inches, latex, acrylic, pen and ink on paper

What I especially liked was the inclusion of Houston area artists, like Dawolu Jabari Anderson, Robert Pruitt, Trenton Doyle Hancock and Tierney Malone. In a show like this, you expect a clever Glenn Ligon, a striking Nick Cave, a powerful Thornton Dial, etc. But when it makes me feel good to see the local guys work side by side with such giants.

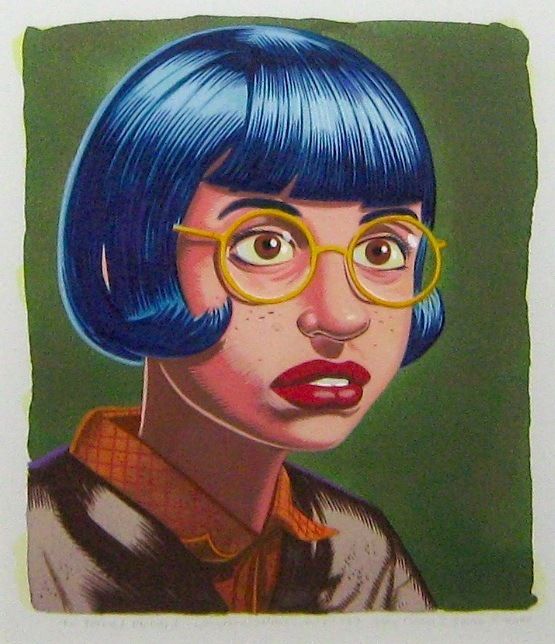

ILYB, Head

I Love You Baby at GalleryHOMELAND, Gspot and Cardoza Gallery.

I Love You Baby (ILYB) was an artist collective started officially in 2002 but unofficially in 1992. It consisted of Paul Kremer, Rodney Chinelliot, Will Bentsen, Chris Olivier and Dale Stewart and included occasional collaborators. They had a three-venue retrospective called We’ve Made a Huge Mistake at Gallery Homeland, Gspot and Cardoza Gallery. I reviewed it and interviewed the surviving members for Glasstire.

ILYB, Boot Face

Michael Tracy, August #2, 2013-2015, Acrylic on cavas over wood, 54 x 48

Michael Tracy at Hiram Butler

This was a very small exhibit--four almost monochromatic canvases--two mostly black and two (like the one above) mostly orange. My knowledge of Michael Tracy's work is quite limited--I've seen a catalog from a P.S. 1 show, Terminal Privileges, and a book from 1992 showing images and writings about a 1990 performance, The River Pierce: Sacrifice II. I'd never seen work of his in person until I saw this show. Tracy had done monochromatic canvases before (as seen in Terminal Privileges), so that part wasn't a surprise. And his performances seem ritualistic and shamanistic, not unlike Yves Klein's, so the existence of monochromatic paintings has perhaps a connection to the void or the infinite.

But these paintings, as well as a series of painted drawings that Mr. Butler showed me, feel like very specific objects instead of representations of abstract ideas. It was ultimately that specificity that appealed to me.

Katie Mulholland, Mad Rad, acrylic on canvas, 20 x 20 inches

Kate Mulholland, Apocalypse Dreams at Scott Charmin.

Kate Mulholland's paintings are created by building paint up then sanding it down, over and over, to create images similar to topographic maps. I saw her show at the Scott Charmin gallery early this year and was so taken by these paintings that I bought the one shown above, Mad Rad. The red and blue parts are so close in value that they vibrate slightly (an effect impossible to capture in a photo). The title made me think of rads as a measure of doses of absorbed radiation. I don't know if that occurred to Mulholland when she titled it Mad Rad, but when I see it, it feels like I am looking at dangerous, radioactive chemicals.

Emily Peacock, Your Middle Class is Showing, 2016, archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

Emily Peacock, User's Guide to Family Business at Beefhaus.

I was up in Dallas to see Jim Nolan's show Welcome Stranger (which was quite enjoyable), and Beefhaus across the street was showing Peacock's User's Guide to Family Business. The pieces in the show, which were made from a variety of media above and beyond Peacock's signature photography, all dealt with death and mortality--specifically with the death of Peacock's mother.

I you had (as I have) been following her work for years (since at least 2011, when I saw work by her in the UH MFA show), you would have seen Peacock's mother and other family members guest-starring in her photos. Whether recreating Diane Arbus pictures or posing as Mary with Peacock as Jesus in Pieta poses, her mother has been a major subject of Peacock's work, and a major collaborator.

But then she died. This show touches on that in various ways. For the Groundbreaking Ceremony is a very black shovel leaning against a wall. Its blackness is achieved by flocking (I suspect that if she could have gotten her hands on some Vantablack, she would have used that instead). In her photo Your Middle Class is Showing, Peacock has taken a picture of her own belly sunburned so that the words "Middle Class" are spelled out in un-sunburned skin. On one hand it's witty--it plays with skin color and by using old English style letters, recalls low-rider lettering. But as I looked at it, I also thought of mortification of the flesh, practices of early Christians to subjugate their sinful flesh. Could deliberately burning herself be a sign of guilt? Whatever the motive, the image is one that stays with you.