Regular readers know I have a small obsession with the Ferus Gallery, which operated in Los Angeles between 1957 and 1967. Part of the reason for the obsession is that Ferus shows how an art scene can develop outside the artistic capital(s)--New York being the capital of the art world at that time. As someone who lives in Houston and is interested in art, I have to believe things like that can happen--that great art scenes can develop far from art capitals. But another reason for my obsession with Ferus is that Ferus has in the past and continues to this very day to impinge on my artistic life--and, it must be added, on the artistic life of Houston, Texas. Why is that?

I think it largely comes down to Walter Hopps. Hopps and Edward Kienholz were the cofounders of the Ferus Gallery. In 1979, Hopps became a consultant for the Menil Foundation, and then director of the Foundation in 1980. He was also the founding director of the Menil Museum when it opened in 1987. So Hopps had a big influence on art in Houston for a long time, and has an influence even now, years after his death. I'm fairly sure he was responsible for bringing Edward and Nancy Reddin Kienholz to Houston (I and a few fellow students spent a life-changing afternoon with them watching old Kienholz documentaries at the Rice Media Center), as well as Robert Irwin (who was an artist in residence at Rice while I was a student there). The Menil Museum has shown lots of the Ferus artists over the years--solo shows for Ken Price, Ed Kienholz, Jay DeFeo and Andy Warhol, and in group shows, work by Price, Kienholz, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, DeFeo, Ed Moses, Ed Ruscha, and Warhol. Many (if not most) of these artists have work in the Menil's permanent collection. There is a show up right now, "Earth Paint Paper Wood: Recent Acquisitions," that includes pieces by Ken Price and Jay DeFeo. So five years after Hopps death, the Menil is still acquiring work by Ferus artists. And tomorrow (October 23, 2010) a gallery show of Larry Bell work is opening at The New Gallery (this show, however, has nothing to do with Hopps, as far as I can tell).

Ferus continues to fascinate me, so I snatched up THE FERUS GALLERY

The book is absolutely gorgeous. The design (by Lorraine Wild) is beautiful, mixing the casual photos of artists and hangers-on with color photos of the art. This is not an approach you see often in art books. If the book is strongly narrative, it usually is all text with a few illustrations of work and a few photos of the subject(s). If it's a monograph, the photos will be pretty much all artwork. McKenna and Wild realized that the snapshots of the artists were part of the story (part of the history) and were generous in reproducing them, along with images of the artwork itself.

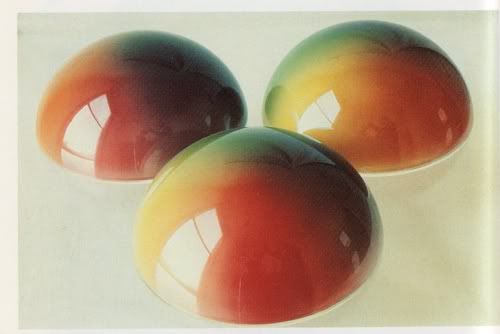

Ken Price, B.G. Red, clay with acrylic and lacquer, 1963

The basic story of the gallery is that Kienholz and Hopps had tried to have their own galleries in the 50s, but were not notably successful. They teamed up to found Ferus. Early on, Ferus showed a lot of San Francisco artists--San Francisco had a better-developed contemporary art scene at the time--along with the youngest, most cutting edge L.A. artists they could find. At some point, Hopps bought out Kienholz's share and brought in Irving Blum as a partner in late 1958. It's unclear if Kienholz left because Blum was coming in or what. It is clear that Kienholz hated Blum and Blum didn't like Kienholz's work. It is funny that both men were partners for Hopps because they seem like complete opposites. In any case, Blum was what the gallery needed--he was suave and could chat up collectors in a way that Kienholz couldn't. Ferus kept exhibiting Kienholz's work until after Hopps left the gallery. At that point, Kienholz's animosity towards Blum caused him to jump ship to the Virginia Dwan Gallery.

In the early 60s, Hopps began curating exhibits for the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum). In 1960, he got a full-time job with the museum and left Ferus (he would become director of the museum in 1963). In a way, The Pasadena Art Museum can be seen as a non-profit Ferus outpost. Hopps displayed a lot of the same artists there. Meanwhile, Ferus displayed more and more of the new New York artists, including Andy Warhol's first solo exhibit in 1962. In that year, Hopps put together the first museum show of pop art--before it had been named--called New Paintings of Common Objects. In 1966, Hopps was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown caused by amphetamine addiction. The Pasadena Art Museum, evidently not wanting a speed freak as a director, fired him. He divorced his wife Shirley (from whom he had been separated for about a year) who then went on to marry Irving Blum the following year! And Ferus closed that year.

This book captures the personal and political dynamics pretty well. There was definitely a group who hated Blum--partly because he came in and brutally cut down the gallery's roster, and partly because he was such a slick rick. Sonia Gechtoff out-and-out accuses him of theft (and adds that she could never understand why Shirley Hopps would leave Walter for Irving).

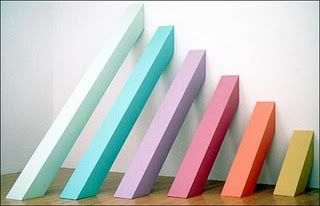

Among the artists, there is camaraderie but also competition. All of the Ferus artists started as more-or-less abstract expressionists (except maybe Ken Price) and quickly moved away from it. Kienholz moved one direction (grungy, socially-aware assemblage), and most of the others moved a different direction (a direction sometimes called "finish fetish" for their use of high-tech manufacturing techniques). They were a bunch of macho sexists who hung out at Barney's Beanery (and, according to Judy Chicago, bragged about their "joints"). Billy Al Bengston was the self-appointed ring-leader and apparently the most competitive of the bunch (it is not surprising that he was also a professional motorcycle racer). Larry Bell remarks that when he started adding industrial glass to his work, Bengston tried to discourage him. Bell realized he had done something that Bengston wished he had done. Perhaps Bengston could see that in the end, he was not going to be top dog. (In my view, the ones art history will remember are Ruscha, Kienholz, Bell, Price, DeFeo and Irwin. And maybe Wallace Berman.)

Larry Bell in his studio, 1961

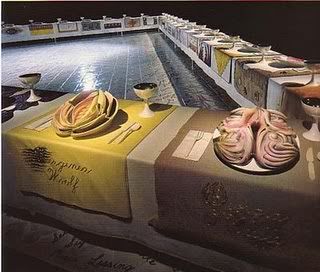

As I said, there are amazing photos in the book. I want to end with one totally insane one:

Jay DeFeo nude in front of The Rose, 1959

No other artist in the book poses nude with one of their artworks (although there are photos of Robert Irwin naked in a bathtub). So you can wonder about a double standard regarding male nudity and female nudity, etc. But I think this photo is awesome. If I were a photographer, I'd try to imitate it and get artists to pose nude in front of their work. I like the concept. Of course, there are some artists here in Houston who I'd very much enjoy seeing nude before their work--for thoroughly dishonorable reasons. But beyond the voyeuristic thrill of it, I like the idea of the artist stripped bare before the world and the work. The work, in many ways, exposes the artist already. Being nude reflects that.