Usually top 10 lists are about one type of thing. Top 10 movies, top 10 books, etc. In the past we've run best-of lists for visual art and performance art. This year, I decided to follow Griel Marcus's example and just list anything I wanted, regardless of genre. This blog is still an art blog, however, so art dominates the list. But it's not all art exhibits. These are exhibits, books, comics, etc., that appealed to me mightily this year.

The list is not in any particular order. There are many items on the "honorable mention" list that could easily have gone in the top 10 list if I thought about it long enough. And these items reflect both my own taste, idiosyncratic as it may be, and what I had access to. (I'm always impressed by critics who seem to have, for example, seen every movie released in a given year. But I'm an amateur part-time art critic, and I know I missed some great exhibits in the past year.) So the way to view this list is not as a top 10 list but rather as a list of things that I considered good in 2013.

Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible, curated by Claire Elliot and Robert Gober (The Menil) and Forrest Bess: Key to the Riddle

It was a Forrest Bess year for me this year. The Menil put together a fine exhibit, which included within it an exhibit originally curated by Robert Gober for the Whitney Biennial. I suspect that the exhibit was what prompted Chuck Smith to turn his 1999 documetary into a book. The documentary is good, but the book is so much better--including complete texts of many Forrest Bess letters and tons of photographs. For me, the exhibit and the book inspired three posts that I'm proud of--first a review of the show, then a recounting of legendary newspaperman Sig Byrd's visit with Bess, and finally an account of my attempt to find the location of Bess's long-gone shack on East Matagorda Bay.

12 Events by the Art Guys

The Art Guys have been a partnership for 30 years. This year, they decided to step away from the baroque style of their more recent projects and do 12 "simple" events. Some involved endurance (walking the length of Little York, the longest street in Houston; doing standup comedy for 8 hours straight), some involved repeating the same absurd action over and over (riding around the 610 Loop over and over for 24 hours; walking around the crosswalks at the intersection of Westheimer and Hillcroft for 8 hours); and some were sui generis (wearing portable fences as they walked around city hall; moving objects counterclockwise from the southernmost, westernmost, northernmost and easternmost points of the city). They concluded by restaging their first event, The Art Guys Agree on Painting, as The Art Guys Agree On Painting, Again, This Time From Thirty Feet Up. 12 Events wasn't just a celebration of their long partnership, it was a tribute to the site of that partnership, the city of Houston.

The Property

This graphic novel (which I reviewed here) by Israeli cartoonist Rutu Modan took the form of a madcap romantic comedy (a delightful one) to deal with the fraught issue of the history of relations between Polish Jews and Gentiles. (See Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945

Sean Shim-Boyle's Salt House at Project Row Houses

To describe what Sean Shim-Boyle did with his Project Row Houses installation is to minimize its impact on the viewer. Nonetheless, here goes. Shim-Boyle took inherent elements of the row house and limited his installation to minimal use of existing elements. Specifically he put a second chimney in and added a new light source in the floor. But the magic was actually being in the space. The angled chimney was uncannily like the original chimney, and by its position made the familiar boxy room of the row house utterly strange. Devon Britt-Darby wrote in Art + Culture Texas, "The criss-crossing lines created by the chimneys, the beams, the windows and shadows give seemingly every vantage point an enchanting division of spaces that cries out for a viewfinder."

Hillerbrand+Magsamen, untitled, 2013, plastic toys, mostly from McDonalds Happy Meals, dimensions variable

Hillerbrand+Magsamen's Stuffed at Brand 10 Artspace

When I saw the above piece in Fort Worth, I instantly thought of Richard Long circles of slate. Long's work suggests to me the deep geologic time of the earth. Hillerbrand+Magsamen's Happy Meal toy version suggests another kind of time--call it "mess time"--the tiny period of time it takes for children to spread toys evenly over the floor space of one's home. It's work that makes you smile, but it also makes you think about the stuff that fills our lives. Mary Magsamen and Stephen Hillerbrand often use their two children in their work (they should get credit!), and much of the work is about being a suburban nuclear family. (I wonder how their work will change when their kids enter adolescence. So far, though, they seem like real good sports about working with mom and dad.) This exhibit was especially about the possessions that fill up a suburban home--the piles of stuff that fill a house, end up in garage sales, Good Will stores, and landfills. It was a playfully absurd exhibit.

Jeremy DePrez, left: Untitled (Milton), 2013, oil and wax on canvas, 82 x 36 inches; and right: Untitled (Harriet), 2013, acrylic on canvas, 82 x 36 inches

Jeff Elrod's and Jeremy Deprez's Fantasy Island at Texas Gallery

I'm not going to pretend I really understand Jeremy DePrez's artwork. On the contrary, I feel like whenever I try to analyze it, I fall flat on my face. That was the case when I looked at his work in his MFA exhibit, and it was the case when I saw his paintings in the Boredom show at Lawndale. I wish I could say I had an "aha!" moment seeing his work displayed with Jeff Elrod's at Texas Gallery. But I did have a revelation: whatever it is that DePrez is doing, I like it. The slightly irregular look of his canvases in this show (the stretchers weren't straight, the parallel lines were broken up) gives the work a carefully constructed feeling of slackness. They get it right by not getting it right. Oh, and the Jeff Elrods were excellent, too.

Brave Genius: A Scientist, a Philosopher, and Their Daring Adventures from the French Resistance to the Nobel Prize

Germany invaded France on May 10, 1940, and in just over a month defeated the French and British armies there. Albert Camus was the editor of a French Resistance newspaper called Combat. Jacques Monod, a biologist, was recruited into the Resistance group Francs-Tireurs et Partisans. When the various Resistance organizations were joined under an umbrella organization, the French Forces of the Interior, Monod was the chief of staff. The writer and biologist didn't meet each other until after the war, however, when they became close friends. Camus continued to write and remained an activist, turning against Communism in the face of the Soviet invasion of Hungary. Monod fought a public battle against the ideologically-motivated Soviet pseudo-science of genetics known as Lysenkoism. Camus died in a car accident in 1960 shortly after winning the Nobel Prize in literature. Monod went on to win a Nobel Prize in medicine for his pioneering genetics work. Only a brief portion of the book that considers the personal friendship of the two men. Instead, Carroll weaves their life stories into the history of the French Resistance, the Hungarian rebellion, the study of genes, etc. In addition to showing the intersections between these two brilliant men, this book manages to show how the advances in biology in the period from just before World War II through the 60s are as much a part of history as anything else--that despite the split of the humanities and science into "two cultures," it is possible to consider them together fruitfully. I could not put Brave Genius down once I started--it was the most compelling book I read all year.

Brandon Araujo's exhibit at Domy Books and New Paintings by Brandon, Dylan, Guillaume and Isaiah at Spring Street Studios

Araujo's paintings have sneaked up on me over the course of the year. I know I have probably seen his work before, but the first time I noticed was at the exhibit at Domy (it was really a "Brandon" show, but Domy was still there). And I wasn't totally sure what to think about it. Then I saw more of his work in the Spring Street group show and finally visited his studio during Artcrawl. Araujo is an artist who is working out his own style, but he is also one whose work has a relationship to work by other artists around his age in Houston. So trying to understand his work is related to the task of trying to understand the work of some of his peers (among whom, the artists in the Spring Street show--Dylan Roberts, Guillaume Gelot and Isaiah López). But these artists aren't the germ of some regional school of painters--there are artists all over who are working in similar areas of abstract painting--Nathan Green, for example. They are sometimes called New Casualists or New Provisionalists. I'm a little loathe to put Araujo in that pigeonhole, particularly so early in his career. I can't put my finger on what I like about it, but the thing is, every time I see his work, I want to see more.

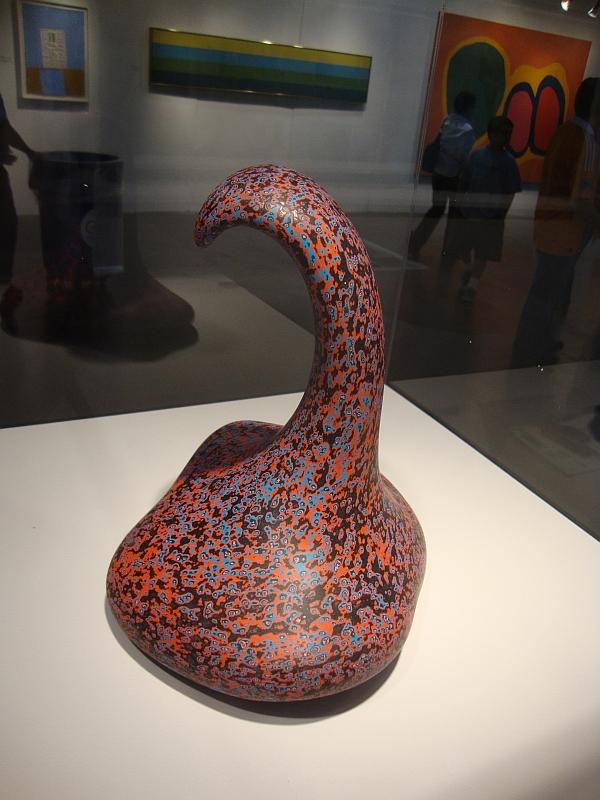

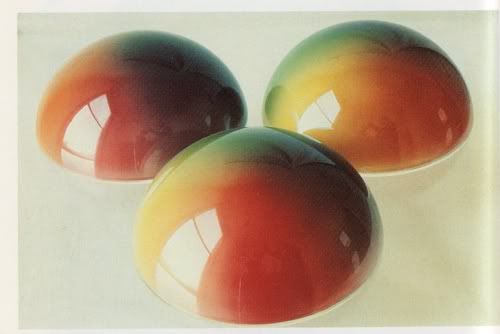

Ken Price, Pastel, 1995, fired and painted clay, 14.5 x 15 x 14 in.

Ken Price Sculpture: A Retrospective at the Nasher Sculpture Center

If you read much about contemporary art, you will have seen over the past few decades a reduction of discussion of craftsmanship in the conversation. This goes doubly so for arts that are traditionally considered part of the craft tradition. But the considerable rise in the critical fortunes of Ken Price recently suggests that the the fortunes of craft may be changing. Price, who died in 2012 just a few months before his retrospective opened at LACMA, was one of the artists associated with the Ferus Gallery. His work has a jazzy West Coast vibe. It's playful and fun. As a ceramicist, Price would make overtures to the traditions of the crafts (his highly abstracted "cups," for example) but was also quite willing to toss tradition completely overboard when it suited him. Seeing a lifetime's work from Price was one of the best museum experiences I had all year.

Sam Zabel and The Magic Pen by Dylan Horrocks

This is an incomplete comics narrative. Every now and then, Horrocks will throw up a new page on his website. He just posted page 103. The first page was posted in 2009. So why call this a 2013 work? I've been following it for quite a while with great pleasure, but it was this year that it really electrified me. The very first page in 2013 plops the protagonist Sam in the middle of an orgy with 50 beautiful green Venusian women (the page reproduced above is the only "SFW" page from that sequence). Now if someone had described this too me, I'd say it sounded like a lame pile of adolescent fantasy wish-fulfillment, and I certainly wouldn't imagine that a cartoonist as sensitive and possessing of moral rectitude as Dylan Horrocks would draw such a thing. And yet, here it is. It isn't ironic--it's eroticism is meant to be erotic. But within the context of the narrative, it works--especially as you see how the rest of 2013's pages unfold. Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen is about the ability of comics to be wish fulfillment. The first part is essentially realistic, a story of a blocked cartoonist. But there is an abrupt switch to the fantastic, specifically magic realism in the sense of Italo Calvino.This feels like it is shaping up to be a sequel of sorts to Hicksville

Honorable mention

- 9.5 Thesis on Art by Ben Davis (Haymarket Books)

- Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me

directed by Drew DeNicola and Oliva Mori

- Inside Llewyn Davis directed by Joel and Ethan Coen

- The Core Fellows exhibit at the Glassell School of Art featuring Andrea Behm, Anna Elise Johnson, Jang Soon Im, Madsen Minax, Miguel Amat, Ronny Quevedo, Senalka McDonald and Tatiana Istomina

- North of South, East of West directed by Meredith Danluck

- The uncontrollable nature of grief and forgiveness (or lack of) by Kathryn Kelley (Art League)

- Within Without the Space of a Corner by Nick Kersulis (Devin Borden Gallery)

- Tracing Our Pilgrimage by Kermit Oliver (Art League)

- Ad Reinhardt: How to Look: Art Comics

with an essay by Robert Storr (Hatje Cantz/David Zwirner)

- Not How It Happened by Joel Ross and Jason Creps (Tiny Park)

- A chain of non-events by Katie Wynne (Lawndale)

- World Map Room

by Yuichi Yokoyama (PictureBox)

- Zinefest