Showing posts with label Larry Bell. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Larry Bell. Show all posts

Monday, November 8, 2010

Friday, October 22, 2010

Note on The Ferus Gallery by Kristine McKenna

by Robert Boyd

Regular readers know I have a small obsession with the Ferus Gallery, which operated in Los Angeles between 1957 and 1967. Part of the reason for the obsession is that Ferus shows how an art scene can develop outside the artistic capital(s)--New York being the capital of the art world at that time. As someone who lives in Houston and is interested in art, I have to believe things like that can happen--that great art scenes can develop far from art capitals. But another reason for my obsession with Ferus is that Ferus has in the past and continues to this very day to impinge on my artistic life--and, it must be added, on the artistic life of Houston, Texas. Why is that?

I think it largely comes down to Walter Hopps. Hopps and Edward Kienholz were the cofounders of the Ferus Gallery. In 1979, Hopps became a consultant for the Menil Foundation, and then director of the Foundation in 1980. He was also the founding director of the Menil Museum when it opened in 1987. So Hopps had a big influence on art in Houston for a long time, and has an influence even now, years after his death. I'm fairly sure he was responsible for bringing Edward and Nancy Reddin Kienholz to Houston (I and a few fellow students spent a life-changing afternoon with them watching old Kienholz documentaries at the Rice Media Center), as well as Robert Irwin (who was an artist in residence at Rice while I was a student there). The Menil Museum has shown lots of the Ferus artists over the years--solo shows for Ken Price, Ed Kienholz, Jay DeFeo and Andy Warhol, and in group shows, work by Price, Kienholz, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, DeFeo, Ed Moses, Ed Ruscha, and Warhol. Many (if not most) of these artists have work in the Menil's permanent collection. There is a show up right now, "Earth Paint Paper Wood: Recent Acquisitions," that includes pieces by Ken Price and Jay DeFeo. So five years after Hopps death, the Menil is still acquiring work by Ferus artists. And tomorrow (October 23, 2010) a gallery show of Larry Bell work is opening at The New Gallery (this show, however, has nothing to do with Hopps, as far as I can tell).

Ferus continues to fascinate me, so I snatched up THE FERUS GALLERY by Kristine McKenna. McKenna is a Los Angeles-based journalist best-known for her interviews. In this book, she tried to talk to a constellation of people associated with the Ferus Gallery--artists, Irving Blum, various collectors, spouses and siblings of key players, etc. For those who died before she could interview them (Hopps and Kienholz especially), she drew from other interviews. Out of this material, she constructed an oral history of the gallery, full of Rashomon-like contradictions. She also borrowed photographs from her subjects, including tons of casual snapshots. The book leads off with biographies of the major characters in the story, then launches into the chronologically arranged oral history.

by Kristine McKenna. McKenna is a Los Angeles-based journalist best-known for her interviews. In this book, she tried to talk to a constellation of people associated with the Ferus Gallery--artists, Irving Blum, various collectors, spouses and siblings of key players, etc. For those who died before she could interview them (Hopps and Kienholz especially), she drew from other interviews. Out of this material, she constructed an oral history of the gallery, full of Rashomon-like contradictions. She also borrowed photographs from her subjects, including tons of casual snapshots. The book leads off with biographies of the major characters in the story, then launches into the chronologically arranged oral history.

The book is absolutely gorgeous. The design (by Lorraine Wild) is beautiful, mixing the casual photos of artists and hangers-on with color photos of the art. This is not an approach you see often in art books. If the book is strongly narrative, it usually is all text with a few illustrations of work and a few photos of the subject(s). If it's a monograph, the photos will be pretty much all artwork. McKenna and Wild realized that the snapshots of the artists were part of the story (part of the history) and were generous in reproducing them, along with images of the artwork itself.

Ken Price, B.G. Red, clay with acrylic and lacquer, 1963

The basic story of the gallery is that Kienholz and Hopps had tried to have their own galleries in the 50s, but were not notably successful. They teamed up to found Ferus. Early on, Ferus showed a lot of San Francisco artists--San Francisco had a better-developed contemporary art scene at the time--along with the youngest, most cutting edge L.A. artists they could find. At some point, Hopps bought out Kienholz's share and brought in Irving Blum as a partner in late 1958. It's unclear if Kienholz left because Blum was coming in or what. It is clear that Kienholz hated Blum and Blum didn't like Kienholz's work. It is funny that both men were partners for Hopps because they seem like complete opposites. In any case, Blum was what the gallery needed--he was suave and could chat up collectors in a way that Kienholz couldn't. Ferus kept exhibiting Kienholz's work until after Hopps left the gallery. At that point, Kienholz's animosity towards Blum caused him to jump ship to the Virginia Dwan Gallery.

In the early 60s, Hopps began curating exhibits for the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum). In 1960, he got a full-time job with the museum and left Ferus (he would become director of the museum in 1963). In a way, The Pasadena Art Museum can be seen as a non-profit Ferus outpost. Hopps displayed a lot of the same artists there. Meanwhile, Ferus displayed more and more of the new New York artists, including Andy Warhol's first solo exhibit in 1962. In that year, Hopps put together the first museum show of pop art--before it had been named--called New Paintings of Common Objects. In 1966, Hopps was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown caused by amphetamine addiction. The Pasadena Art Museum, evidently not wanting a speed freak as a director, fired him. He divorced his wife Shirley (from whom he had been separated for about a year) who then went on to marry Irving Blum the following year! And Ferus closed that year.

This book captures the personal and political dynamics pretty well. There was definitely a group who hated Blum--partly because he came in and brutally cut down the gallery's roster, and partly because he was such a slick rick. Sonia Gechtoff out-and-out accuses him of theft (and adds that she could never understand why Shirley Hopps would leave Walter for Irving).

Among the artists, there is camaraderie but also competition. All of the Ferus artists started as more-or-less abstract expressionists (except maybe Ken Price) and quickly moved away from it. Kienholz moved one direction (grungy, socially-aware assemblage), and most of the others moved a different direction (a direction sometimes called "finish fetish" for their use of high-tech manufacturing techniques). They were a bunch of macho sexists who hung out at Barney's Beanery (and, according to Judy Chicago, bragged about their "joints"). Billy Al Bengston was the self-appointed ring-leader and apparently the most competitive of the bunch (it is not surprising that he was also a professional motorcycle racer). Larry Bell remarks that when he started adding industrial glass to his work, Bengston tried to discourage him. Bell realized he had done something that Bengston wished he had done. Perhaps Bengston could see that in the end, he was not going to be top dog. (In my view, the ones art history will remember are Ruscha, Kienholz, Bell, Price, DeFeo and Irwin. And maybe Wallace Berman.)

Larry Bell in his studio, 1961

As I said, there are amazing photos in the book. I want to end with one totally insane one:

Jay DeFeo nude in front of The Rose, 1959

No other artist in the book poses nude with one of their artworks (although there are photos of Robert Irwin naked in a bathtub). So you can wonder about a double standard regarding male nudity and female nudity, etc. But I think this photo is awesome. If I were a photographer, I'd try to imitate it and get artists to pose nude in front of their work. I like the concept. Of course, there are some artists here in Houston who I'd very much enjoy seeing nude before their work--for thoroughly dishonorable reasons. But beyond the voyeuristic thrill of it, I like the idea of the artist stripped bare before the world and the work. The work, in many ways, exposes the artist already. Being nude reflects that.

Regular readers know I have a small obsession with the Ferus Gallery, which operated in Los Angeles between 1957 and 1967. Part of the reason for the obsession is that Ferus shows how an art scene can develop outside the artistic capital(s)--New York being the capital of the art world at that time. As someone who lives in Houston and is interested in art, I have to believe things like that can happen--that great art scenes can develop far from art capitals. But another reason for my obsession with Ferus is that Ferus has in the past and continues to this very day to impinge on my artistic life--and, it must be added, on the artistic life of Houston, Texas. Why is that?

I think it largely comes down to Walter Hopps. Hopps and Edward Kienholz were the cofounders of the Ferus Gallery. In 1979, Hopps became a consultant for the Menil Foundation, and then director of the Foundation in 1980. He was also the founding director of the Menil Museum when it opened in 1987. So Hopps had a big influence on art in Houston for a long time, and has an influence even now, years after his death. I'm fairly sure he was responsible for bringing Edward and Nancy Reddin Kienholz to Houston (I and a few fellow students spent a life-changing afternoon with them watching old Kienholz documentaries at the Rice Media Center), as well as Robert Irwin (who was an artist in residence at Rice while I was a student there). The Menil Museum has shown lots of the Ferus artists over the years--solo shows for Ken Price, Ed Kienholz, Jay DeFeo and Andy Warhol, and in group shows, work by Price, Kienholz, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, DeFeo, Ed Moses, Ed Ruscha, and Warhol. Many (if not most) of these artists have work in the Menil's permanent collection. There is a show up right now, "Earth Paint Paper Wood: Recent Acquisitions," that includes pieces by Ken Price and Jay DeFeo. So five years after Hopps death, the Menil is still acquiring work by Ferus artists. And tomorrow (October 23, 2010) a gallery show of Larry Bell work is opening at The New Gallery (this show, however, has nothing to do with Hopps, as far as I can tell).

Ferus continues to fascinate me, so I snatched up THE FERUS GALLERY

The book is absolutely gorgeous. The design (by Lorraine Wild) is beautiful, mixing the casual photos of artists and hangers-on with color photos of the art. This is not an approach you see often in art books. If the book is strongly narrative, it usually is all text with a few illustrations of work and a few photos of the subject(s). If it's a monograph, the photos will be pretty much all artwork. McKenna and Wild realized that the snapshots of the artists were part of the story (part of the history) and were generous in reproducing them, along with images of the artwork itself.

Ken Price, B.G. Red, clay with acrylic and lacquer, 1963

The basic story of the gallery is that Kienholz and Hopps had tried to have their own galleries in the 50s, but were not notably successful. They teamed up to found Ferus. Early on, Ferus showed a lot of San Francisco artists--San Francisco had a better-developed contemporary art scene at the time--along with the youngest, most cutting edge L.A. artists they could find. At some point, Hopps bought out Kienholz's share and brought in Irving Blum as a partner in late 1958. It's unclear if Kienholz left because Blum was coming in or what. It is clear that Kienholz hated Blum and Blum didn't like Kienholz's work. It is funny that both men were partners for Hopps because they seem like complete opposites. In any case, Blum was what the gallery needed--he was suave and could chat up collectors in a way that Kienholz couldn't. Ferus kept exhibiting Kienholz's work until after Hopps left the gallery. At that point, Kienholz's animosity towards Blum caused him to jump ship to the Virginia Dwan Gallery.

In the early 60s, Hopps began curating exhibits for the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum). In 1960, he got a full-time job with the museum and left Ferus (he would become director of the museum in 1963). In a way, The Pasadena Art Museum can be seen as a non-profit Ferus outpost. Hopps displayed a lot of the same artists there. Meanwhile, Ferus displayed more and more of the new New York artists, including Andy Warhol's first solo exhibit in 1962. In that year, Hopps put together the first museum show of pop art--before it had been named--called New Paintings of Common Objects. In 1966, Hopps was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown caused by amphetamine addiction. The Pasadena Art Museum, evidently not wanting a speed freak as a director, fired him. He divorced his wife Shirley (from whom he had been separated for about a year) who then went on to marry Irving Blum the following year! And Ferus closed that year.

This book captures the personal and political dynamics pretty well. There was definitely a group who hated Blum--partly because he came in and brutally cut down the gallery's roster, and partly because he was such a slick rick. Sonia Gechtoff out-and-out accuses him of theft (and adds that she could never understand why Shirley Hopps would leave Walter for Irving).

Among the artists, there is camaraderie but also competition. All of the Ferus artists started as more-or-less abstract expressionists (except maybe Ken Price) and quickly moved away from it. Kienholz moved one direction (grungy, socially-aware assemblage), and most of the others moved a different direction (a direction sometimes called "finish fetish" for their use of high-tech manufacturing techniques). They were a bunch of macho sexists who hung out at Barney's Beanery (and, according to Judy Chicago, bragged about their "joints"). Billy Al Bengston was the self-appointed ring-leader and apparently the most competitive of the bunch (it is not surprising that he was also a professional motorcycle racer). Larry Bell remarks that when he started adding industrial glass to his work, Bengston tried to discourage him. Bell realized he had done something that Bengston wished he had done. Perhaps Bengston could see that in the end, he was not going to be top dog. (In my view, the ones art history will remember are Ruscha, Kienholz, Bell, Price, DeFeo and Irwin. And maybe Wallace Berman.)

Larry Bell in his studio, 1961

As I said, there are amazing photos in the book. I want to end with one totally insane one:

Jay DeFeo nude in front of The Rose, 1959

No other artist in the book poses nude with one of their artworks (although there are photos of Robert Irwin naked in a bathtub). So you can wonder about a double standard regarding male nudity and female nudity, etc. But I think this photo is awesome. If I were a photographer, I'd try to imitate it and get artists to pose nude in front of their work. I like the concept. Of course, there are some artists here in Houston who I'd very much enjoy seeing nude before their work--for thoroughly dishonorable reasons. But beyond the voyeuristic thrill of it, I like the idea of the artist stripped bare before the world and the work. The work, in many ways, exposes the artist already. Being nude reflects that.

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Tiptoeing through the Tulips

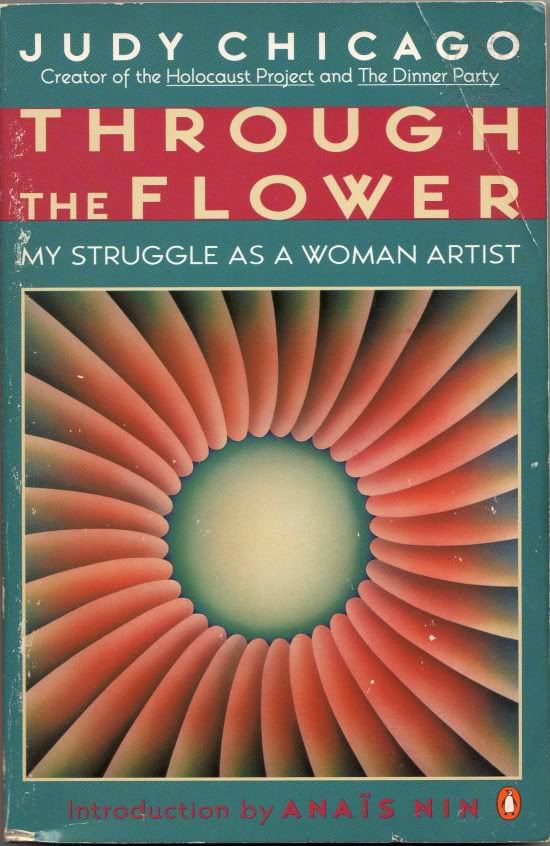

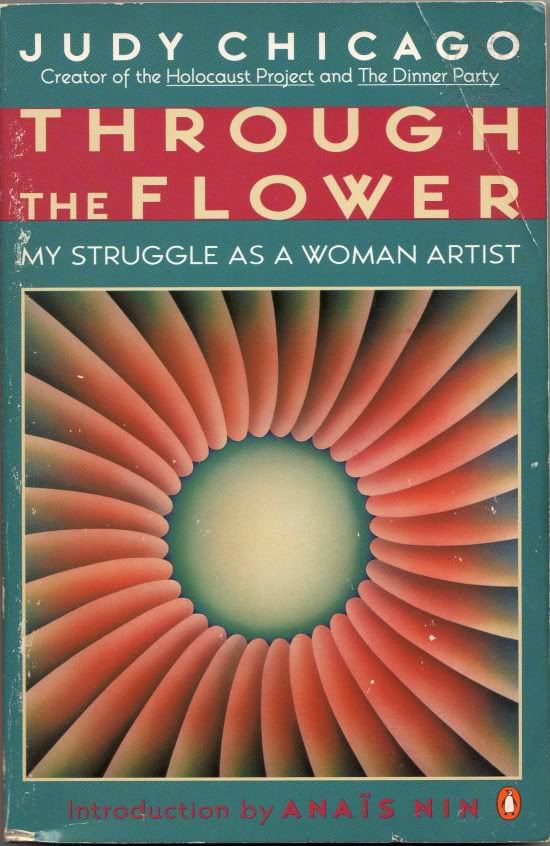

It's intellectually risky for a dude to approach feminism and feminist art. But I just read Through the Flower by Judy Chicago, and it's really interesting, so I'm going to try to tiptoe through the subject (but will probably end up blundering about). Through the Flower was written originally in 1975, before she finished her most famous piece, The Dinner Party (1974-1979). This one is a new edition from 1993. I found it at Half Price Books, and as luck would have it, it's an autographed copy.

Chicago began her career as an artist in the 1960s in Los Angeles. She was one of the L.A. style minimalists, and as such, her work embraced high-tech fabrication, a high level of craftsmanship, and a certain playfulness. Think of artists like John McCracken and the Ferus boys--Ken Price, Craig Kauffman, Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston and Larry Bell. Chicago was doing pieces like this:

Judy Chicago, Car Hood, sprayed acrylic lacquer on a 1964 Corvair hood, 1963-64

You can definitely see the resemblance between what she was doing and what Billy Al Bengston was doing. And there is a high level of craft here. But she had an ambiguous relationship with craft. In Through the Flower, she sees craft as a thing that boys learned as a matter of course (in shop class) but that girls did not. I think this is really arguable, and that in a way, she is seeing craft through male eyes if she sees it that way. There were (and are) traditionally female crafts that few boys learn. Sewing and needlework, for example. I think an issue was that such crafts were not looked at as art--and that is a male failing. That they weren't looked at as craft in the context of Chicago's book is a failing on her part.

In her desire to acquire craftsmanlike skills (above and beyond what was taught to her in art school), she took a class in auto-body painting (the only woman with 250 men in the class) and another in pyrotechnics (!)--which feel totally like "boy" things to learn. Perhaps she felt she had to do these things to compete in a man's world. Certainly the piece above speaks to manly kind of things--custom car culture, in particular. (Custom car culture was a big influence on other artists in L.A. at the time, especially Robert Irwin.)

She tried to fit in with the art scene of L.A. of the early 60s. Now readers of this blog know I have often expressed admiration for the Ferus scene. Chicago--without naming names (damn!)--paints a less attractive picture.

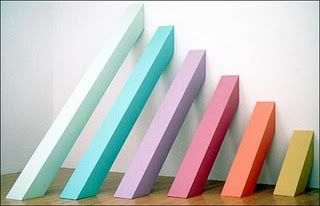

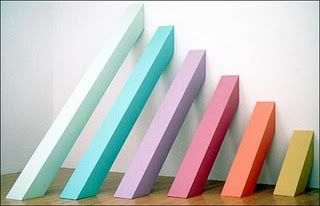

Judy Chicago, Rainbow Picket, originally sculpted in 1966 and recreated in 2004

Rainbow Picket is awesome! The colors, the angle, the way it fits against the wall. It would stand proudly next to a Sol Lewitt, a Dan Flavin, a John McCracken.

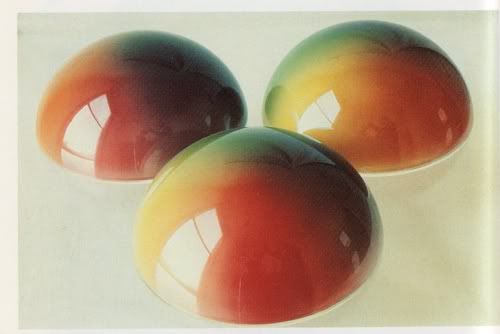

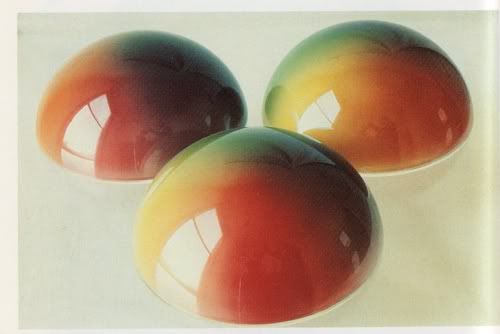

Judy Chicago, Red Dome Set, sprayed acrylic lacquer on formed acrylic, 1968

This is another really cool minimal piece. But again, Chicago felt like she was hiding from herself. In retrospect, she believes that in these round forms, her female nature is trying to come through, but she didn't want to believe it at the time. She describes how a woman artist from New York (who?) visited her studio and saw these pieces. She said, "Ah, the Venus of Willendorf." Chicago was crushed because she took it as a critical, cutting remark, and also because this woman had seen through her minimalist defenses.

So she embraced feminism. She educated herself on woman artists through history (there is a great chapter here on what she learned looking at their work, as well as studying the great women writers and thinkers). She found other women artists who had seen the sexist environment of the art world and of society in general, and who wanted to do something about it. Chicago befriended an older artist, Miriam Schapiro, and they began to work together on feminist art classes and spaces, including Womanhouse and a feminist program at CalArts.

Chicago and Schapiro eventually split their partnership over an ideological disagreement. Chicago was, essentially, a separatist. She wasn't an extreme separatist (she was married to a man, after all), but she thought there should be an entirely separate art world for women--all woman art classes, women's galleries, etc. Schapiro, rightly I think, wanted to work within the system and evolve it from within. Whatever problems she had with CalArts, she thought it was still worth fighting the battle there. And I think Schapiro was right, basically. The art world, for itrs many faults, is a less sexist place than many other parts of society. (At least, that's how it seems to me--but I'm a guy after all.)

Chicago also rejected abstraction, and started drawing and painting a lot of flowers and vaginas. Also doing a lot more performance--cartoonish plays like "Cock and Cunt," but also shamanistic performance like Woman/Atmosphere.

Judy Chicago, Woman/Atmosphere, fireworks and painted body, 1971

Despite a change in subject matter towards the real and away from the abstract, her basic painting style--mostly hard-edged with smooth, spray-painted gradations of color, remained the same. (Which reminds of Philip Guston, who around the same time also went from doing abstract paintings to figurative paintings--but his skittery bruch style and his pallet remained constant.)

Obviously her journey of self-discovery was leading somewhere. And we now know where:

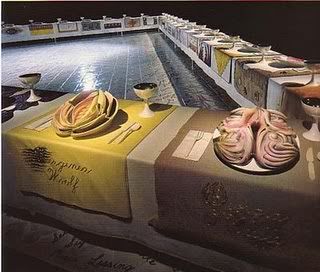

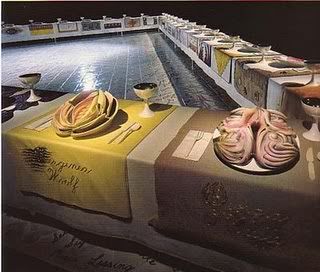

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, ceramic, porcelain, textile, 1974-79

This is her most famous work. Generally, Chicago doesn't seem to be a major figure in recent art history. It may be because people see a work like The Dinner Party and feel it is too literal, too obvious. My feeling is, so what? It's so beautiful and so cool. That outweighs the hit-you-on-the-head obviousness of it. But at the same time, I think her early minimal pieces are great, too, and really underrated. (At least, what I've seen of them.)

Feminist art is something I really want to learn more about. Fortunately, there is a movie that I think is going to be key for understanding this movement that is premiering right now at the Toronto Film Festival. It's called Women Art Revolution--A Secret History. The director, Lynn Hershman, has been working on it literally for decades. I saw a short preview of it at the Cinema Arts Festival, and it looks really good.

Chicago began her career as an artist in the 1960s in Los Angeles. She was one of the L.A. style minimalists, and as such, her work embraced high-tech fabrication, a high level of craftsmanship, and a certain playfulness. Think of artists like John McCracken and the Ferus boys--Ken Price, Craig Kauffman, Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston and Larry Bell. Chicago was doing pieces like this:

Judy Chicago, Car Hood, sprayed acrylic lacquer on a 1964 Corvair hood, 1963-64

You can definitely see the resemblance between what she was doing and what Billy Al Bengston was doing. And there is a high level of craft here. But she had an ambiguous relationship with craft. In Through the Flower, she sees craft as a thing that boys learned as a matter of course (in shop class) but that girls did not. I think this is really arguable, and that in a way, she is seeing craft through male eyes if she sees it that way. There were (and are) traditionally female crafts that few boys learn. Sewing and needlework, for example. I think an issue was that such crafts were not looked at as art--and that is a male failing. That they weren't looked at as craft in the context of Chicago's book is a failing on her part.

In her desire to acquire craftsmanlike skills (above and beyond what was taught to her in art school), she took a class in auto-body painting (the only woman with 250 men in the class) and another in pyrotechnics (!)--which feel totally like "boy" things to learn. Perhaps she felt she had to do these things to compete in a man's world. Certainly the piece above speaks to manly kind of things--custom car culture, in particular. (Custom car culture was a big influence on other artists in L.A. at the time, especially Robert Irwin.)

She tried to fit in with the art scene of L.A. of the early 60s. Now readers of this blog know I have often expressed admiration for the Ferus scene. Chicago--without naming names (damn!)--paints a less attractive picture.

Halfway through my last year in graduate school, I became involved with a gallery run by a man named Rolf Nelson. He used to take me to the artists' bar, Barney's Beanery, where all the artists who were considered "important" hung out. They were all men, and they spent most of their time talking about cars, motorcycles, women, and their "joints."A piece like Car Hood (which is excellent, in my opinion) was her way of trying to demonstrate to them that she could be a "tough" artist like them. She writes about her work then as hiding her real self in an attempt to fit in (to "pass"?). And maybe so, but look at this piece:

Judy Chicago, Rainbow Picket, originally sculpted in 1966 and recreated in 2004

Rainbow Picket is awesome! The colors, the angle, the way it fits against the wall. It would stand proudly next to a Sol Lewitt, a Dan Flavin, a John McCracken.

Judy Chicago, Red Dome Set, sprayed acrylic lacquer on formed acrylic, 1968

This is another really cool minimal piece. But again, Chicago felt like she was hiding from herself. In retrospect, she believes that in these round forms, her female nature is trying to come through, but she didn't want to believe it at the time. She describes how a woman artist from New York (who?) visited her studio and saw these pieces. She said, "Ah, the Venus of Willendorf." Chicago was crushed because she took it as a critical, cutting remark, and also because this woman had seen through her minimalist defenses.

So she embraced feminism. She educated herself on woman artists through history (there is a great chapter here on what she learned looking at their work, as well as studying the great women writers and thinkers). She found other women artists who had seen the sexist environment of the art world and of society in general, and who wanted to do something about it. Chicago befriended an older artist, Miriam Schapiro, and they began to work together on feminist art classes and spaces, including Womanhouse and a feminist program at CalArts.

Chicago and Schapiro eventually split their partnership over an ideological disagreement. Chicago was, essentially, a separatist. She wasn't an extreme separatist (she was married to a man, after all), but she thought there should be an entirely separate art world for women--all woman art classes, women's galleries, etc. Schapiro, rightly I think, wanted to work within the system and evolve it from within. Whatever problems she had with CalArts, she thought it was still worth fighting the battle there. And I think Schapiro was right, basically. The art world, for itrs many faults, is a less sexist place than many other parts of society. (At least, that's how it seems to me--but I'm a guy after all.)

Chicago also rejected abstraction, and started drawing and painting a lot of flowers and vaginas. Also doing a lot more performance--cartoonish plays like "Cock and Cunt," but also shamanistic performance like Woman/Atmosphere.

Judy Chicago, Woman/Atmosphere, fireworks and painted body, 1971

Despite a change in subject matter towards the real and away from the abstract, her basic painting style--mostly hard-edged with smooth, spray-painted gradations of color, remained the same. (Which reminds of Philip Guston, who around the same time also went from doing abstract paintings to figurative paintings--but his skittery bruch style and his pallet remained constant.)

Obviously her journey of self-discovery was leading somewhere. And we now know where:

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, ceramic, porcelain, textile, 1974-79

This is her most famous work. Generally, Chicago doesn't seem to be a major figure in recent art history. It may be because people see a work like The Dinner Party and feel it is too literal, too obvious. My feeling is, so what? It's so beautiful and so cool. That outweighs the hit-you-on-the-head obviousness of it. But at the same time, I think her early minimal pieces are great, too, and really underrated. (At least, what I've seen of them.)

Feminist art is something I really want to learn more about. Fortunately, there is a movie that I think is going to be key for understanding this movement that is premiering right now at the Toronto Film Festival. It's called Women Art Revolution--A Secret History. The director, Lynn Hershman, has been working on it literally for decades. I saw a short preview of it at the Cinema Arts Festival, and it looks really good.

Monday, October 5, 2009

The Cool School

Robert Boyd

In 1992, I saw an art exhibit in Los Angeles called "Helter Skelter," which was devoted to Los Angeles art. From that moment, I became interested in art from L.A., an interest that deepened when I lived in L.A. for a couple of years. And I already had a long-standing interest in the work of Edward Kienholz, dating back to when he had a show at the late, lamented Rice Art Gallery, where a bunch of us film class students saw a couple of films with him and Nancy Reddin dating from the early and mid-60s, one a television documentary about him and one an incredible documentary of the reception of his show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1966. Of course, Kienholz had started the Ferus Gallery with Walter Hopps, who was the founding director of the Menil Museum and an important person in the art scene in Houston in the 1980s. All this is just to say that the L.A. art scene has long been a fascination of mine. So when I heard about Ferus Gallery documentary, The Cool School (2007), I had to check it out.

The documentary starts with a description of the Watts Towers (which was one of the first things I went to see when I moved to L.A. the first time). This struck me as a bit contrived, but at the same time typical. Advanced, alternative art scenes always reach out and try to include outsider or vernacular arts. Look at Picasso and his gang bringing Henri Rousseau into their fold, or here in Houston, the way the recently closed show "No Zoning" included Cleveland "The Flower Man" Turner as part of the show. I am really torn by this because it seems to have a touch of slumming about it, but at the same time I love these outsider, vernacular works. It is often the alternative arts community that finds and embraces these works and recognizes their creators. (Think of how Henry Darger's work was saved, for example.) Anyway, this has little to do with the documentary--it's in my mind because of a conversation I had Saturday night with Matthew Guest (who is, not surprisingly, also interested in outsider art). The filmmakers seem to be suggesting that artistically, L.A. was kind of barren except for the Watts Towers, which were decidedly out of the mainstream.

There were a few collectors who were into modern art, and a few artists who were trying things here and there, but no art infrastructure. Edward Kienholz and Walter Hopps had each tried to start galleries without much success. So the decided to join forces. They were definitely an odd couple. Kienholz was a burly, working-class beatnik rebel, Hopps a skinny nervous egghead with thick glasses. They founded the Ferus gallery on La Cienega. The problem was that they really weren't great partners. But they both had a great vision for art in L.A. and a recognition that cutting edge artists needed a place to display their work.They founded the gallery in 1957, opening with a group show of abstract expressionist painting by San Francisco and L.A. artists. This is something the movie underscores--the early days of Ferus were somewhat dominated by San Franciscans, because San Francisco had a much better developed art scene than L.A. Obviously Clyfford Still was the biggest name there--he was one of the most important abstract expressionist artists. But it seems that there was a whole beatnik art scene there that was vital and healthy. It is also my impression that only in San Francisco was the visual art scene dominated by beatniks. The beats were literary and a lifestyle, and the only artists that I think of part of that subculture were San Franciscans like Jay DeFeo (who had a solo show at Ferus in 1960).

But the presence of Ferus really energized L.A. artists. Many of them lived in Venice, which was a slum at the time. They mostly came out of abstract expressionism, but moved towards other styles in the late 50s and early 60s. For example, Robert Irwin (another artist who visited Rice while I was there--I wonder if Walter Hopps was involved in bringing him and Kienholz to the campus?) started off as an abstract expressionist, but apparently decided his paintings were no damn good after seeing some Philip Guston abstract paintings. So he pared back the expression to some very simple geometric paintings, that evolved into nearly invisible painted objects that were all about light.

This move away from abstract expressionism to minimalism was happening in New York, too. Ditto with the Pop idea, which at Ferus was exemplified by Edward Ruscha's paintings and photos. Ditto with assemblage, with Kienholz as a leader. I think this may have led New Yorkers to look on L.A. as just a bunch of copycats (this point of view was represented by Ivan Karp in the movie). But I think it was in the air--the L.A. artists were working their way out of abstract expressionism just as the New York artists were, and these routes were logical reactions to that older style.

And there were also things in L.A. that really had no counterpart in New York, like Ken Price's ceramic pieces. Clay just wasn't taken seriously in most places as a legitimate medium for a fine artist.

The first year of Ferus had its first controversy--a Wallace Berman show that was busted for being pornographic. Berman was one of those shamanic figures in art who is better known as an influence than as an artist--but his art is astounding. Unfortunately, the experience of being busted made him swear off working with commercial galleries.

What happened next is unclear. The movie suggests that Hoops convinced Kienholz to spend more time on his art and bought him out, and that later Irving Blum entered the picture as a new partner. But the book Ferus says that Kienholz was getting burned out and that Blum was brought in to buy him out. Either way, the net result was that the rough-hewn Kienholz was out and the suave Blum was in. (Whatever the reason, Kienholz started exhibiting at the Dwan Gallery in the early 60s. Did he harbor a grudge against Ferus?)

The still above in the movie was actually taken from the T.V. show at the time about Kienholz. It's worth mentioning that Kienholz wasn't chosen because the producers necessarily thought he was a great artist, but because he was sort of a living embodiment of the cliches that viewers might have about "beatnik artists." The TV series itself focused each week on a different profession (this week, and artist, next week, a hotel chef).

Barney's Beanery was their hangout--it was located right around the corner pretty much. I ate there a lot when I lived in L.A. (It was founded in 1920 and is still there.)

sign on the outside of the Beanery

Irving Blum was exactly what the gallery needed. He was seriously into avant garde art and had a great eye, but he was also the kind of personable, sophisticated fellow who could chat up well-to-do collectors. A gallery is a commercial enterprise, and while history (if you're lucky) remembers the artists, the collectors are every bit as important.

(Walter Hoops is the second from the left, and Irving Blum is the smiling man with the crew cut standing to Hopp's right.)

Hopp's story of how he met Blum and brought him on board is amusing but a little hard to believe. As Hopps would have it, Blum comes into the gallery one day with a group of swell friends and starts explaining the art as if he owns the joint. Hopps pulls him aside and says, hey buddy, I think you and I should go have a drink. I couple of drinks later at the Beanery, and Blum is officially on board.

Blum brought a fundamentally more professional outlook to the enterprise. Hopps and Kienholz had exhibited something like 70 artists year (lots of group shows), but Blum cut it down to a core group of L.A. artists, which would be supplemented by the occasional New York artist and group shows. The key Ferus artists were John Altoon, Craig Kaufman, Ken Price, Ed Kienholz, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, and Ed Ruscha. The interesting thing is that many of these artists are not particularly well-known today. The only ones who I'd say are part of the standard art history of the '60s onward are Kienholz, Irwin, Ruscha, and maybe Bell. (Your mileage may vary, however.) This may be a result of the lingering bias against non-New York artists, or may be because art by, say, Craig Kaufman wasn't as interesting as, say, Donald Judd's art. On different days, I can lean to different explanations.

But what is important is that while Ferus was there, these artists had a leg to stand on and were able to develop (which they did--a lot). That period in L.A., from 1957 to 1967 saw an explosion of modern art. Hopps left Ferus in 1962 to become curator and director of the Pasadena Art Museum--where he put on a bunch of cutting edge shows. The L.A. County Museum was opened (next to the tar pits!) and it had some important shows, including the controversial Kienholz show. Other galleries opened. Artforum moved from San Francisco to L.A. But as John Baldessari comments in the film, it all wound down in the late '60s. Ferus closed, Artforum moved away to New York. Despite Blum's best efforts in cultivating collectors (including Hollywood types like Dennis Hopper and Dean Stockwell, both of whom are in the documentary), he apparently wasn't doing that great. He eventually moved to New York. (He did make one absolutely amazing art purchase in L.A.--he gave Andy Warhol his first gallery show--a bunch of painted Campbell's Soup cans. A few people, including Dennis Hopper, bought individual paintings for $100 each. But Blum decided at the end of the show that he wanted them all as a set--so he asked his collectors if he could return their money, and paid Warhol $1000--in installments--for all of them.) Baldessari describes modern art in L.A. as a boom and bust phenomenon--although he adds hopefully that it seems like the scene in L.A. now is fully self-sustaining.

Dennis Hopper and Irving Blum

One thing that killed the Ferus vibe for everyone, apparently, was the death of John Altoon in 1968. The Ferus guys had more or less been a bunch of buddies hanging out together, and at a reunion filmed for this documentary, they seem to say that Altoon's death ended that. Irwin doesn't totally agree--he thinks that they were all evolving as artists in different directions and moving out of Venice and even out of L.A. But Altoon's death certainly provides a sense of finality to the Ferus era.

Surviving Ferus artists posing for a photo

Indeed, this film is haunted by death. The one guy you would like to hear from most, Ed Kienholz, had died in 1994. There is some archival footage of him, but not enough. And Walter Hopps died while this film was being made.

Kienholz being buried in his classic Packard--even his funeral was a work of art

Because you can see how important Ferus was to the ecology of art in L.A., it is kind of an exemplar for any provincial city that is growing an art scene. Houston lucked out a bit by having two very sophisticated collectors, John and Dominique De Menil, who were also really into social engagement. What Ferus (and Hopps, Kienholz, and Blum) were to L.A., the Menils were to Houston. The Cool School is a good way to experience a fascinating bit of American art history.

In 1992, I saw an art exhibit in Los Angeles called "Helter Skelter," which was devoted to Los Angeles art. From that moment, I became interested in art from L.A., an interest that deepened when I lived in L.A. for a couple of years. And I already had a long-standing interest in the work of Edward Kienholz, dating back to when he had a show at the late, lamented Rice Art Gallery, where a bunch of us film class students saw a couple of films with him and Nancy Reddin dating from the early and mid-60s, one a television documentary about him and one an incredible documentary of the reception of his show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1966. Of course, Kienholz had started the Ferus Gallery with Walter Hopps, who was the founding director of the Menil Museum and an important person in the art scene in Houston in the 1980s. All this is just to say that the L.A. art scene has long been a fascination of mine. So when I heard about Ferus Gallery documentary, The Cool School (2007), I had to check it out.

The documentary starts with a description of the Watts Towers (which was one of the first things I went to see when I moved to L.A. the first time). This struck me as a bit contrived, but at the same time typical. Advanced, alternative art scenes always reach out and try to include outsider or vernacular arts. Look at Picasso and his gang bringing Henri Rousseau into their fold, or here in Houston, the way the recently closed show "No Zoning" included Cleveland "The Flower Man" Turner as part of the show. I am really torn by this because it seems to have a touch of slumming about it, but at the same time I love these outsider, vernacular works. It is often the alternative arts community that finds and embraces these works and recognizes their creators. (Think of how Henry Darger's work was saved, for example.) Anyway, this has little to do with the documentary--it's in my mind because of a conversation I had Saturday night with Matthew Guest (who is, not surprisingly, also interested in outsider art). The filmmakers seem to be suggesting that artistically, L.A. was kind of barren except for the Watts Towers, which were decidedly out of the mainstream.

There were a few collectors who were into modern art, and a few artists who were trying things here and there, but no art infrastructure. Edward Kienholz and Walter Hopps had each tried to start galleries without much success. So the decided to join forces. They were definitely an odd couple. Kienholz was a burly, working-class beatnik rebel, Hopps a skinny nervous egghead with thick glasses. They founded the Ferus gallery on La Cienega. The problem was that they really weren't great partners. But they both had a great vision for art in L.A. and a recognition that cutting edge artists needed a place to display their work.They founded the gallery in 1957, opening with a group show of abstract expressionist painting by San Francisco and L.A. artists. This is something the movie underscores--the early days of Ferus were somewhat dominated by San Franciscans, because San Francisco had a much better developed art scene than L.A. Obviously Clyfford Still was the biggest name there--he was one of the most important abstract expressionist artists. But it seems that there was a whole beatnik art scene there that was vital and healthy. It is also my impression that only in San Francisco was the visual art scene dominated by beatniks. The beats were literary and a lifestyle, and the only artists that I think of part of that subculture were San Franciscans like Jay DeFeo (who had a solo show at Ferus in 1960).

But the presence of Ferus really energized L.A. artists. Many of them lived in Venice, which was a slum at the time. They mostly came out of abstract expressionism, but moved towards other styles in the late 50s and early 60s. For example, Robert Irwin (another artist who visited Rice while I was there--I wonder if Walter Hopps was involved in bringing him and Kienholz to the campus?) started off as an abstract expressionist, but apparently decided his paintings were no damn good after seeing some Philip Guston abstract paintings. So he pared back the expression to some very simple geometric paintings, that evolved into nearly invisible painted objects that were all about light.

This move away from abstract expressionism to minimalism was happening in New York, too. Ditto with the Pop idea, which at Ferus was exemplified by Edward Ruscha's paintings and photos. Ditto with assemblage, with Kienholz as a leader. I think this may have led New Yorkers to look on L.A. as just a bunch of copycats (this point of view was represented by Ivan Karp in the movie). But I think it was in the air--the L.A. artists were working their way out of abstract expressionism just as the New York artists were, and these routes were logical reactions to that older style.

And there were also things in L.A. that really had no counterpart in New York, like Ken Price's ceramic pieces. Clay just wasn't taken seriously in most places as a legitimate medium for a fine artist.

The first year of Ferus had its first controversy--a Wallace Berman show that was busted for being pornographic. Berman was one of those shamanic figures in art who is better known as an influence than as an artist--but his art is astounding. Unfortunately, the experience of being busted made him swear off working with commercial galleries.

What happened next is unclear. The movie suggests that Hoops convinced Kienholz to spend more time on his art and bought him out, and that later Irving Blum entered the picture as a new partner. But the book Ferus says that Kienholz was getting burned out and that Blum was brought in to buy him out. Either way, the net result was that the rough-hewn Kienholz was out and the suave Blum was in. (Whatever the reason, Kienholz started exhibiting at the Dwan Gallery in the early 60s. Did he harbor a grudge against Ferus?)

The still above in the movie was actually taken from the T.V. show at the time about Kienholz. It's worth mentioning that Kienholz wasn't chosen because the producers necessarily thought he was a great artist, but because he was sort of a living embodiment of the cliches that viewers might have about "beatnik artists." The TV series itself focused each week on a different profession (this week, and artist, next week, a hotel chef).

Barney's Beanery was their hangout--it was located right around the corner pretty much. I ate there a lot when I lived in L.A. (It was founded in 1920 and is still there.)

sign on the outside of the Beanery

Irving Blum was exactly what the gallery needed. He was seriously into avant garde art and had a great eye, but he was also the kind of personable, sophisticated fellow who could chat up well-to-do collectors. A gallery is a commercial enterprise, and while history (if you're lucky) remembers the artists, the collectors are every bit as important.

(Walter Hoops is the second from the left, and Irving Blum is the smiling man with the crew cut standing to Hopp's right.)

Hopp's story of how he met Blum and brought him on board is amusing but a little hard to believe. As Hopps would have it, Blum comes into the gallery one day with a group of swell friends and starts explaining the art as if he owns the joint. Hopps pulls him aside and says, hey buddy, I think you and I should go have a drink. I couple of drinks later at the Beanery, and Blum is officially on board.

Blum brought a fundamentally more professional outlook to the enterprise. Hopps and Kienholz had exhibited something like 70 artists year (lots of group shows), but Blum cut it down to a core group of L.A. artists, which would be supplemented by the occasional New York artist and group shows. The key Ferus artists were John Altoon, Craig Kaufman, Ken Price, Ed Kienholz, Ed Moses, Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, and Ed Ruscha. The interesting thing is that many of these artists are not particularly well-known today. The only ones who I'd say are part of the standard art history of the '60s onward are Kienholz, Irwin, Ruscha, and maybe Bell. (Your mileage may vary, however.) This may be a result of the lingering bias against non-New York artists, or may be because art by, say, Craig Kaufman wasn't as interesting as, say, Donald Judd's art. On different days, I can lean to different explanations.

But what is important is that while Ferus was there, these artists had a leg to stand on and were able to develop (which they did--a lot). That period in L.A., from 1957 to 1967 saw an explosion of modern art. Hopps left Ferus in 1962 to become curator and director of the Pasadena Art Museum--where he put on a bunch of cutting edge shows. The L.A. County Museum was opened (next to the tar pits!) and it had some important shows, including the controversial Kienholz show. Other galleries opened. Artforum moved from San Francisco to L.A. But as John Baldessari comments in the film, it all wound down in the late '60s. Ferus closed, Artforum moved away to New York. Despite Blum's best efforts in cultivating collectors (including Hollywood types like Dennis Hopper and Dean Stockwell, both of whom are in the documentary), he apparently wasn't doing that great. He eventually moved to New York. (He did make one absolutely amazing art purchase in L.A.--he gave Andy Warhol his first gallery show--a bunch of painted Campbell's Soup cans. A few people, including Dennis Hopper, bought individual paintings for $100 each. But Blum decided at the end of the show that he wanted them all as a set--so he asked his collectors if he could return their money, and paid Warhol $1000--in installments--for all of them.) Baldessari describes modern art in L.A. as a boom and bust phenomenon--although he adds hopefully that it seems like the scene in L.A. now is fully self-sustaining.

Dennis Hopper and Irving Blum

One thing that killed the Ferus vibe for everyone, apparently, was the death of John Altoon in 1968. The Ferus guys had more or less been a bunch of buddies hanging out together, and at a reunion filmed for this documentary, they seem to say that Altoon's death ended that. Irwin doesn't totally agree--he thinks that they were all evolving as artists in different directions and moving out of Venice and even out of L.A. But Altoon's death certainly provides a sense of finality to the Ferus era.

Surviving Ferus artists posing for a photo

Indeed, this film is haunted by death. The one guy you would like to hear from most, Ed Kienholz, had died in 1994. There is some archival footage of him, but not enough. And Walter Hopps died while this film was being made.

Kienholz being buried in his classic Packard--even his funeral was a work of art

Because you can see how important Ferus was to the ecology of art in L.A., it is kind of an exemplar for any provincial city that is growing an art scene. Houston lucked out a bit by having two very sophisticated collectors, John and Dominique De Menil, who were also really into social engagement. What Ferus (and Hopps, Kienholz, and Blum) were to L.A., the Menils were to Houston. The Cool School is a good way to experience a fascinating bit of American art history.

Labels:

Ed Kienholz,

Ed Ruscha,

Jay DeFeo,

Ken Price,

Larry Bell,

Robert Irwin,

Wallace Berman,

Walter Hopps

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)