Yasuaki Onishi, Reverse of Volume RG, 2012, plastic sheeting and black hot glue

Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. I say the strongest emotion, because I am satisfied the ideas of pain are much more powerful than those which enter on the part of pleasure. Without all doubt, the torments which we may be made to suffer are much greater in their effect on the body and mind, than any pleasures which the most learned voluptuary could suggest, or than the liveliest imagination, and the most sound and exquisitely sensible body, could enjoy. Nay, I am in great doubt whether any man could be found, who would earn a life of the most perfect satisfaction at the price of ending it in the torments, which justice inflicted in a few hours on the late unfortunate regicide in France. But as pain is stronger in its operation than pleasure, so death is in general a much more affecting idea than pain; because there are very few pains, however exquisite, which are not preferred to death: nay, what generally makes pain itself, if I may say so, more painful, is, that it is considered as an emissary of this king of terrors. When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances, and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are, delightful,as we every day experience. [Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 1757]

Thus, too, delight in the sublime in nature is only negative (whereas that in the beautiful is positive): that is to say, it is a feeling of imagination by its own act depriving itself of its freedom by receiving a final determination in accordance with a law other than that of its empirical employment. In this way it gains an extension and a might greater than that which it sacrifices. But the ground of this is concealed from it, and in its place it feels the sacrifice or deprivation, as well as its cause, to which it is subjected. The astonishment amounting almost to terror, the awe and thrill of devout feeling, that takes hold of one when gazing upon the prospect of mountains ascending to heaven, deep ravines and torrents raging there, deep shadowed solitudes that invite to brooding melancholy, and the like-all this, when we are assured of our own safety, is not actual fear.

This makes it evident that true sublimity must be sought only in the mind of the judging subject, and not in the object of nature that occasions this attitude by the estimate formed of it. Who would apply the term “sublime” even to shapeless mountain masses towering one above the other in wild disorder, with their pyramids of ice, or to the dark tempestuous ocean, or such like things? But in the contemplation of them, without any regard to their form, the mind abandons itself to the imagination and to a reason placed, though quite apart from any definite end, in conjunction therewith, and merely broadening its view, and it feels itself elevated in its own estimate of itself on finding all the might of imagination still unequal to its ideas. [Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Judgment, 1790]

When we think of the sublime, we think of the landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich--solitary figures dwarfed by immense mountains, oceans, icebergs, etc. Current artists who tread this ground are James Turrell (who is constantly installing sublime-appreciation devices called Skyspaces wherever someone will pay him to do so) and Olafur Eliasson.

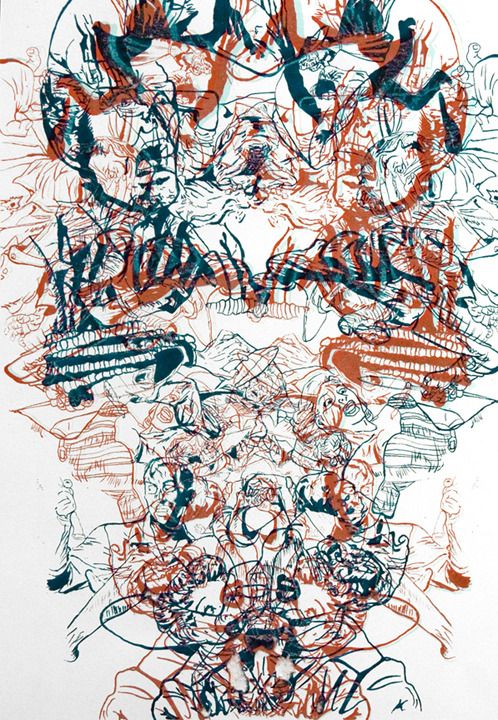

Should I add Yasuaki Onishi to that list? I mean, look at that snowy valley between those mountains! The awe-inspiring immensity! The soul-crushing depth! The craggy terror! It sure looks pretty sublime to me.

Oh, wait.

That's upside down. Sorry. This is what it really looks like.

Yasuaki Onishi, Reverse of Volume RG, 2012, plastic sheeting and black hot glue

This is the view from the inside. From what I understand, Onishi stacked up a bunch of boxes in the Rice Gallery. Then he draped those boxes with wrinkled plastic sheeting. Then he attached the sheeting to the ceiling with strings (I can't tell if the strings are made of dripped hot glue or if he just used strings to guide the hot glue drips--or something else altogether). Then he removed the boxes--leaving this negative space that looks strikingly like rugged, snowy mountains. The plastic looks like snow and the black hot glue looks like exposed rock.

Yasuaki Onishi, Reverse of Volume RG, 2012, plastic sheeting and black hot glue

This is a view of Reverse of Volume RG from the outside, where you can see the strings. This is what you see before you walk into the Rice Gallery. So in a sense, before you experience the landscape, you see the method by which it was made. And for some, that might break the magic spell.

But once you are under the sheet, with the omnipresent glow of the floor-hugging lights, it's a pretty impressive sight. It surrounds you with this strange upside-down mountain-scape. On one hand, Onishi is undermining the sense of the sublime--by showing the backdrop, the view behind the facade, the trickery. He undermines the idea of the sublime by using cheap, disposable materials like plastic sheeting and hot glue.

But then he creates this all-surrounding environment that is quite powerful. I hardly think that for most people it will inspire "terror," but I bet there are quite a few exclamations of "Oh, wow!" Onishi, in the end, flips back and forth between an attempt at creating a sublime experience and an undermining of that experience. In this way, his art seems a bit more humane and grounded than Turrell's.