William Powhida and Jade Townsend, Map of the town of New New Berlin

This map greeted visitors to New New Berlin and the Nevada Art Fair, an installation by William Powhida and Jade Townsend, at the Galveston Artists Residency last weekend. Bill Arning is identified as mayor. Given that this entire installation is a satire of Houston and of the art world, it's not exactly a compliment. But why Arning and not, say, Gary Tinterow? Because back in 2012, the following quote appeared in Art in America:

“Moving to Houston four years ago I had no idea I would find an art scene so vibrant, international and spirited,” CAMH director Bill Arning told A.i.A. over the weekend. “I keep telling artist friends that it's the new Berlin: cheap rents; great galleries, museums, and collectors; and a regular flow of visits from the best artists working today.” [Paul Laster, Art in America, October 21, 2012]Or maybe they were thinking of this quote:

First off I tell artists it's the new Berlin: cheap rent, a global audience, scores of supportive venues. It's an amazing life for art makers. ["Interview; Bill Arning Director Of The CAMH HOUSTON the `New Berlin`", Maria Chavez, Zip Magazine, August 28, 2013]First Arning is stabbed in the back by an artist he's exhibiting, now this: Arning portrayed as the huckster selling Houston to the art world, not so different in the spirit from the ad the Allen Brothers placed in newspapers across America in 1836.

The installation makes snotty fun of Houston, but isn't very deep. I'll outsource most of my opinions to Bill Davenport's great review in Glasstire, which can be summed up with one phrase: "simplistic carpetbagging."

entryway to New New Berlin

New New Berlin had privatized security, of course.

A saloon/whorehouse (where the warm whiskey was free if you were wearing a cowboy hat). The bartender was artist Brian Piana.

And David McClain played the reactionary newspaperman, who from time to time came out to read what seemed like a completely unhinged rant. It turned out to be from "The Alamo," Michael Bise's passionate but confusing editorial that ran in July in Glasstire.

And naturally there was a money-grubbing church complete with a Dan Flavin-style cross. The preacher was Emily Sloan, who has a lot of relevant experience given her "Southern Naptist Convention" and "Carrie Nation" performances.

William Powhida & Jade Townsend, ABMB Hooverville, 2010, Graphite on paper. 40 x 60 inches

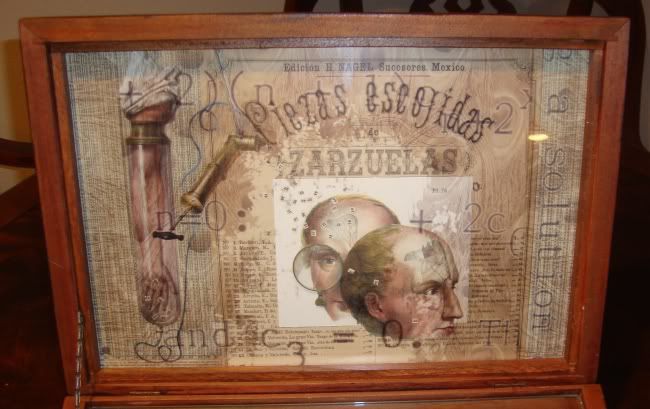

It was the "Flavin" cross that caught my eye. As satirists of Houston, Townsend and Powhida aren't brilliant. But as satirists of the art world, they're quite clever. Their collaborative drawing ABMB Hooverville imagined the glitterati of the art world living in a shanty town on the beach, for example. Much of Powhida's solo work spells out (quite literally) his disgust with the crass Veblen-esque corruption that typifies so much of the upper level, blue chip art world.

Typical of his work is to make a list--"Why You Should Buy Art", "Some Cynical Advice to Artists", "What Can the Art World Teach You", etc.--and then carefully draw it. I don't mean calligraphy (although that is a part of it). What Powhida does is to make a list or piece of text or diagram on a piece of paper and then carefully draw the piece of paper as an object.

William Powhida, What Has the Art World Taught Me

New New Berlin and the Nevada Art Fair are full of lists and signs.

The newspaper's editorial policy is a satire of corporate media.

The military/police/prison industrial complex gets the works, too.

And here is a map of the Nevada Art Fair.

And you can see Powhida's hand in them. The content is sarcastic and the writing is recognizable. But while the newspaper editorial policies and White Horse Security Services seem obvious and heavy handed, the more art related stuff seems funnier and stronger. Like the fact that you in the floor plan for Nevada (itself a take-off of the NADA art fair), the booth for Non-Profits is completely closed off.

The one building in New New Berlin that really works on this level is the Livery Stable. It reflects a common trajectory of post-industrial structures. First a structure may be a factory or a warehouse--a working building. Then after a while, that function no longer exists (in America, at least). The building becomes derelict until someone has the bright idea of handing it over to artists for studios. The artists move into this shitty but indestructible structure and turn it into a lively space for art. The once derelict neighborhood the building occupied gets a few bars and restaurants and becomes "hip." The owner of what was a white-elephant can now sell out to a developer who will put condos in the old warehouse after giving the artists the boot. It's an old story, and what I like about Townsend and Powhida is that they relate it to the old West (a livery stable being the nastiest building in town, and one devoted to work) and include the whole cycle in a series of overlapping signs--the "Artists Studios" banner that overlaps the "Livery Stable" sign, the "Luxury Condos" sign that is pasted on top of the "For Sale Sign".

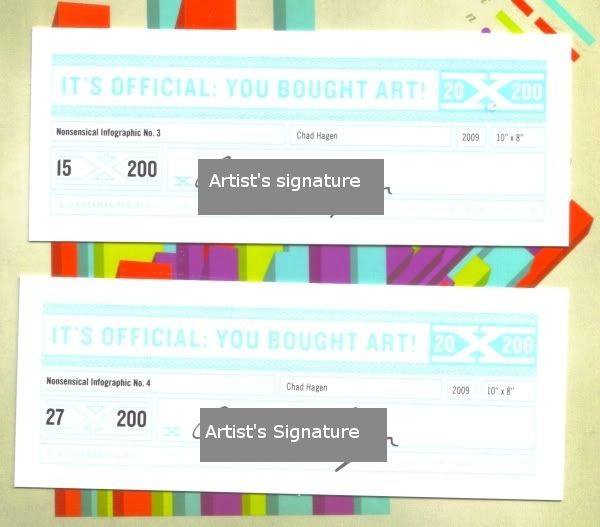

Nevada Art Fair shooting gallery

The best part of the installation was the shooting gallery. Several "artworks" were hung on the far wall of the GAR gallery, and visitors had the opportunity to fire paintball guns at them. They were in "booths" for various galleries, such as David Zwirnered and the Joanna Picture Club (to give it a little local flavor).

Participants could fire paint guns at the pictures, which over the evening became encrusted with paintball residue. Shooters were in theory limited to five shots each, but many of these nice, liberal artsy types went hog wild as soon they got a gun in their hands, firing dozens of shots while Jade Townsend yelled "Only five shots per person!" in irritation.

Jade Townsend firing in the shooting gallery

David McClain takes a shot

Hyperallergic editor Hrag Vartanian was there, and he commented that the paintings almost looked like contemporary abstractions one could see at a real art fair. That made me think of"zombie formalism," the term that Jerry Saltz recently applied to so much contemporary abstract painting. So what do you think, readers? Could any of these paintings go toe-to-toe with Lucien Smith, Dan Colen, Parker Ito or Jacob Kassay?

So New New Berlin and the Nevada Art Fair weren't entirely successful as works of participatory art, but shooting paintballs at canvases was a whole lot of fun. All art fairs should include a paintball firing range.