I know I'm a little late on this. I wish I could say the reason is that I am going to have some startling original insights on the state of contemporary art or the art world. But really, this is the first big art fair I've ever attended. I was more like the hillbilly visiting the city, slack-jawed and saying "Gaw-ly!" In fact, I'll outsource my opinions to other writers who have had a little more time to process this phenomenon. And in between, I show some pictures of art that intrigued (or outraged) me.

(This post is divided into four parts not because any given part is long, but because so many artists were discussed, I kept running out of room to tag the posts. I only get 200-odd characters for labels.)

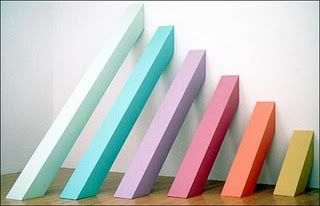

John McCracken, Galaxy, 2008 at David Zwirner

Some galleries were practically like museums--at least in terms of how well-known the work being shown was. David Zwirner was such a gallery.

Dan Flavin, untitled (to dear, durable Sol from Stephen, Sonja, and Dan) one, 1969 at David Zwirner

But Frieze was no museum. I met my friends Mark and Paul there. Both are collectors. Paul is an art fair veteran while Mark had never bought anything from an art fair. Mark was curious why they existed. Indeed, it seems strange that you would go to a tent on an island to see work from galleries that are open all year round in Chelsea. (That said, galleries from all around the world had booths here, so there's that.) This was something that Peter Schjeldahl remarked on in The New Yorker:

The whole idea of staging art fairs in New York may seem odd. Isn't the city a permanent art fair, with hundreds of galleries conveniently clustered in a few neighborhoods? But the gallery-centered template of the art business has changed, and the survival of New York dealers, as of dealers everywhere, now demands that they transport their goods and their personnel from their galleries, which present art with museum-like tenderness and gravitas, to the flimsily walled, cacophonous fairs, even if the trip spans just a few blocks. ["All is Fairs" by Peter Schjedahl, The New Yorker, May 7, 2012]As a gallery owner friend once told me, he can see as many people in one fair as he might see in his gallery all year. So to answer Mark's question, art fairs exist to make money for galleries. A fair is a concentrated locus of buying and selling. A few people at Frieze were like me--looky-loos with no intention (and no means) of buying the art on display. But a good portion of the attendees were serious buyers. And based on what's been reported, they bought big.

Lisson Gallery had a good opening day at Frieze New York:I was intrigued that high-tech electronic artwork such as the work by Mirza--full of parts that will wear out and become obsolete in a few years--sold so well. But what I think of as salable artwork (paintings primarily, and photos, and some sculpture) goes out the window at a high-end art fair like Fireze. If you can afford to pay $50,000 for a work of art, you can afford to take care of it, even if it is electronic, even if it requires constant monitoring, and even if it requires expensive modifications to your home to display it.

Ai Weiwei Marble Helmet, 2010 Sold for €50,000

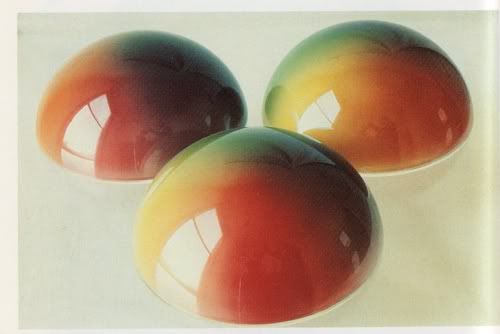

Anish Kapoor Untitled, 2012 Stainless steel and lacquer Sold for £500,000

Haroon Mirza Scream Heist, 2012, Monitor, table top, speaker cable, amp, DVD/AV player, LEDs, Sold for £30,000 / $50,000

Haroon Mirza Rhizomatic, 2012 LCD monitor, strobe, amp, wood, LED’s, circuits Sold for £24,000 / $40,000

Haroon Mirza Important Information, 2012 modified LED display, headphones Sold for £22,000 / $36,000 ["Lisson Sells at Frieze NY" by Marion Maneker, Art Market Monitor, May 3, 2012]

Navid Nuur, Mineralium, 2011-2012, sugar, magnets and iron filings at Alex Zachary Peter Currie

Navid Nuur, Mineralium, 2011-2012, sugar, magnets and iron filings at Alex Zachary Peter Currie

Mineralium by Navid Nuur is literally a pile of sugar and iron filings. Presumably, if you wanted to display this in your house, Nuur would have to personally come and install it. But does sugar last? And doesn't it attract pests? But presumably anyone with the wherewithal to buy this piece also has the means to store it safely.

Buster Graybill, Progeny of Tush Hog at Jack Hanley Gallery

Austin's Buster Graybill had this work, Progeny of Tush Hog, for sale at Jack Hanley Gallery. That yellow stuff is corn, I think. And that's the idea--these objects are meant to be filled with corn and left out in a field, where wild pigs or other critters can root under them and roll them around (causing more corn to fall out). So to own these (properly, at least), you need a ranch out in the country and you need to refill them with corn periodically.

Jim Lambie, Vortex 'Eau de Parfum,' 2012 at Anton Kern Gallery

This piece by Jim Lambie at Anton Kern Gallery, for example, would require their owner to literally build a wall for it, as the "vortex" portion of it is a fairly deep hole the wall.

Cory Arcangel, Bowl of Soggy Cornflakes at Team Gallery

And the funniest example of this is this bowl of soggy cornflakes by Cory Arcangel. I was at the Team Gallery booth looking at some wall tags for a piece of art when I saw a wall-tag that didn't seem to be for any visible piece. It was Bowl of Soggy Cornflakes by Cory Arcangel. I looked around, and sure enough, on the table where the booth employees sat was a bowl of soggy cornflakes. I asked about it and was told that what you got was the bowl, the spoon, a set of instructions, and a certificate of authenticity. You had to supply the cornflakes and milk, and the contents had to be renewed every eight hours. The Team Gallery gallerina I spoke with described the work as a parody of conceptual artworks that were series of instructions--for example, a Sol Lewitt wall drawing. But I think Cory Arcangel was also making fun of art fairs and the people who buy art in them. What was the most ridiculous thing that someone would buy? (I have an email into Team Gallery asking if it sold, and for how much. If they answer, I'll let you know.)

In any case, a person like me with a decent but relatively modest income needs to step outside his worldview to begin to understand what was happening at Frieze.

At Cheim & Read’s booth, partner and sales director Adam Sheffer was practically giddy. “It feels like 2007 all over again!” he exclaimed. The booth sold several Jenny Holzer pieces — an LED sign for $175,000, a bench for $100,000, as well as a work via JPEG — as well as a Chantal Joffe painting for $65,000, a Louise Fishman work for $125,000, and a Bill Jensen for $25,000. Reportedly on reserve was the 2,000-pound Lynda Benglis sculpture oozing out of the corner of the booth, which required the gallery to reinforce the floors underneath in advance of the opening.

London’s Victoria Miro sold several recent works “in the low to mid-six figures” by Yayoi Kusama, who has seen a rush of fresh interest on the heels of her Tate retrospective. “People are incredibly happy to be here,” said dealer James Cohan, who sold a number of pieces by Berlin-based Simon Evans for $30,000 to $75,000 by early afternoon. “They all say, ‘I guess this is going to become the fair in New York.’”

The swift sales continued over at Metro Pictures, where Robert Longo’s large, black-and-white close-up drawing of a waving American flag sold for $425,000 and a Cindy Sherman photograph from 1977 sold for $950,000. Casey Kaplan and Andrea Rosen reported selling out, or very nearly selling out, everything they had on the walls. Kaplan presented a solo show of Garth Weiser’s large, bright abstractions ($35,000-45,000 each). Rosen mounted a solo room of brand new vibrant paintings and wall collages by Elliott Hundley, all sold for $85,000, and an accompanying room of quieter work by Wolfgang Tillmans and Aaron Bobrow, among others. “I tend to bring work under $100,000 to Frieze,” Rosen said. “People who come here like to feel a sense of discovery, but also buy work they know is still reasonably established.” ["Sales Report: Frieze New York Makes a Convincing Case for Itself With an Opening Burst of Business" by Shane Ferro and Julie Halperin, Blouin Artinfo, May 4, 2012]Buying work under $100,000 gives the buyer a sense of discovery?

Lynda Benglis, Quartered Meteor, 1969-1975, lead (yes, lead as in the metal) at Cheim and Read

Sean Landers, Around the World Alone (Ancient Mariner) (left) and Around the World Alone (Slocum) (right), 2011, encaustic, terracotta. metal, wood at greengrassi

Sean Landers, Around the World Alone (Ancient Mariner) (left) and Around the World Alone (Slocum) (right), 2011, encaustic, terracotta. metal, wood at greengrassi

These Sean Landers are perfect for the kid's room!

Paul McCarthy, White Snow Dwarf, Sleepy #1 (Midget), 2012, slilcone (blue) at Hauser & Wirth

Everyone seemed to love the facility. Instead of holding Frieze in an existing building, the organizers built their own mile-long temporary structure. Lord knows what it cost.

Let’s begin with the location, for which there has been endless hand-wringing amongst art worlders. How will we ever get to Randall’s Island? Get a grip, people. A ferry to the Island runs every 15 minutes from 35th street and it’s fucking luxurious. Frieze doesn’t feel like a fair, it feels like an event. It’s not quite Venice, but then again most vaporetti don’t have concession stands. [...]

Once inside, the first thing you’ll notice is the design of the fair. Literally everyone we talked to mentioned how much they liked the lighting, which during the day is mostly natural and augmented by giant hanging fluorescents. We also noticed the spacious layout and booth size. Smaller booths rarely looked cramped, and larger booths often had large window like views into their spaces. So. Great.

But also: Buyer beware. Some art looks better here than it will in your home, which is, well, dangerous, given that a lot of the work is also pretty great. ["The Lowdown on Frieze New York" by Paddy Johnson, Art Fag City, May 4, 2012]And this was part of the feeling of exclusivity that the organizers sought to create. This was evident in many ways. The ticket price ($40/day was meant to frighten away the looky-loos). The curated selection of galleries, which is apparently unusual if I am reading some accounts correctly. (How do other art fairs select their galleries?) The high quality cuisine--whereas if you have a fair in a convention center, you end up with food from whatever concessions monopoly has the contract (think Aramark).

And while Frieze co-founder Matthew Slotover tells the NYT that he is “very much pro-democratization and a larger engagement” with the general public, the fair’s location on a desolate island, and its sky-high entry fee, and even its galleries all mitigate against that. It’s the galleries who asked for — and received — fewer visitors, remember, and on Friday night I met one gallerist who was complaining that while she met some very high-end collectors on Thursday, the Friday crowd had altogether far too many “lookie-loos”. ["The Business of Art Fairs" by Felix Salmon, May 6, 2012](That gallerist was evidently talking about me and my ilk.)

Making my way into the immense white tent that houses the fair, I was shocked. The spaces are wide-open, well lit, generously proportioned, accommodating, sensual. Ceilings soar; a gentle curve in the tent stops vertigo. "How could an art fair feel good?" I wondered. The two-piered New York Armory Show has become drudgy, crowded, comfortably numb. By now I simply assumed that a big art fair in New York wasn't possible. Then I understood what made this art fair completely different than our own: Oxford!

The founders of this fair are Frieze magazine's English executive publishers, Amanda Sharp and Matthew Slotover. In New York and America, we're great at making things big and democratic, and bigger is better — the largest fair, the most galleries, turnover, largest crowds, two piers. That is why the Armory Show is more like a gloomy zoo, giant but visually dreary, shoddy-feeling, and unpleasant. Worse, because it's democratic about which galleries may participate, the quality level is low. By contrast, the Frieze Fair mirrors the fact that the art business is not democratic but is based on a semblance of talent and ability, a quasi-meritocracy. The fair exudes a tribal feeling. This may strike some as elitist or about who-you-know, but it's actually a good thing, because the Frieze fair is a much better reflection of the serious-gallery landscape than the Armory Show is. An American group starting a fair would find it uncomfortable to screen galleries. The English, by contrast, view it as a responsibility. That process has the added benefit of taking a place that has often become strictly a trading floor and returning it, somewhat, to being a powwow, one where information, not just money, changes hands. ["Why the Frieze Art Fair Could Solve the New York Art Fair Problem" by Jerry Saltz, New York, May 5, 2012](Continued in Frieze New York, part 2)