It's convenient that almost all the visual art on public display is inside the Loop, indeed in six specific inner loop neighborhoods--the Museum District, Montrose, the West End, the Heights, Downtown and (increasingly) the East End (with a few outposts in the 3rd Ward and the 5th Ward). Convenient for people like me who go to see multiple art shows every weekend. But it's also unfortunate that the vast majority of the Houston area, that part outside the Loop, is pretty much an art-free zone. So it was surprising and kind of exciting that

The New Black, Contemporary Concepts in Color and Abstraction was opening in the lobby of

Williams Tower (formerly Transco Tower), the tallest building in the Galleria area. He was a show of four abstract painters doing uncompromising work. And it was not in the "safe" environs of one of the Colquitt galleries or Lawndale or Box 13. I'm always intrigued by art like this:

Myke Venable, Venetian Blue/Cobalt Blue/Fluorescent Yellow, acrylic on canvas, 2010

Myke Venable, Venetian Blue/Cobalt Blue/Fluorescent Yellow, acrylic on canvas, 2010

In an environment like this:

Philip Johnson and John Burgee, Williams Tower, 1983

Philip Johnson and John Burgee, Williams Tower, 1983

Its many tenants include energy companies, insurance companies, real estate developers (including

Hines, which developed this building and many of the most architecturally memorable buildings in Houston), law firms, financial service firms, HR firms, and banks. At least half of them come in through this lobby every morning. So this show was seen by a lot of white collar workers who probably have no idea what to make of it. And they may, therefore, be hostile to it.

I spoke about this to Myke Venable at the opening. He told how it had been difficult to explain to his family what he was doing, and he mentioned it to an art professor who reminded Myke that he had been studying art for several years, and that his family had never studied art. It's simply a fact to appreciate modern art or contemporary art is something that requires long exposure or education. That said, because of influential modernist designers like

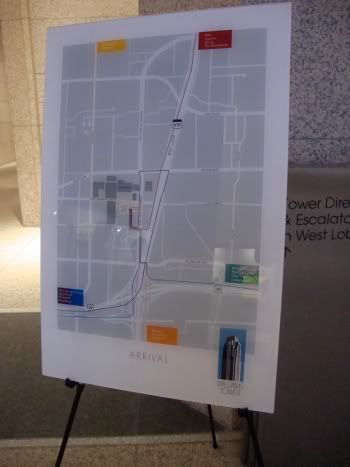

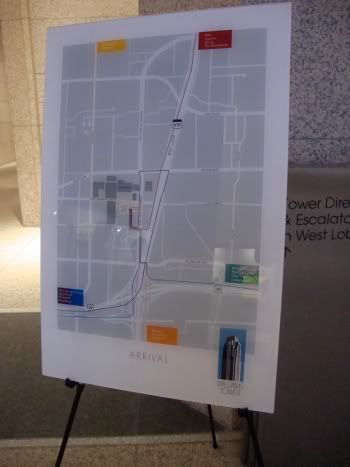

Paul Rand, we see geometric abstractions in the form of maps and info-graphics every day. For example, in the lobby of Williams Tower--right in amongst the art--were a pair of signs like this.

I wonder if any of the office workers made a connection.

Anyway, the show is really good. It was an unusual collection of artists--three geometric abstractionists and one more gestural, painterly abstractionist, Veneman. They could also perhaps be divided into artists who were influenced by natural forms (Guidry and maybe Veneman) and one whose work recalled architecture (Leach) and one whose work was so completely abstract that it seemed divorced from the world of things we see.

Michael Guidry seems to be working from actual landscapes, which he abstracts to the simplest possible groupings of colors.

Michael Guidry, Your Messed Up Life Still Thrills Me, latex on canvas over wood panel, 2010

Michael Guidry, Your Messed Up Life Still Thrills Me, latex on canvas over wood panel, 2010

Please excuse my bad photographic skills--this is the only Guidry I shot that was in focus. And unfortunately, it is the least recognizable as a landscape (except for its basically horizontal composition). The way he deals with landscape reminds me of early, primitive three-dimensional renderings of landscapes on computer. By simplifying the forms down to a minimum of colors and complex polygon shapes, computers could process the data it took to depict a viewpoint moving through space in a landscape. Because this was just a moment in the history of computer graphics, it gives Guidry's landscapes a curiously nostalgic look. It's as if he is saying that when computer artists learned to create super-realistic depictions of

places, as in

Avatar, they lost something. I think so, too.

Jonathan Leach takes a more architectural approach to his straight-edge paintings. I reviewed

his show at Sonya Roesch last year, and some of those pieces are also shown here. But there are a lot of newer pieces as well. Leach's work is characterize by bright, fluorescent colors (hard to photograph adequately, alas) and extremely hard-edges. The paint is applied with a minimum of gesture, but is not perfectly flat. You can still see the parallel lines caused by the brush, or the dots of raised canvas. The exception to this is when Leach paints on the opposite side of clear plexiglass (a technique that

Jim Nutt also used in his early paintings), which gives a supersmooth, somewhat inhuman look to the work. He plays with this effect in Move Me, where he paints on both the back and the front of a sheet of plexiglass.

Jonathan Leach, Move Me, acrylic on plexiglass, 2010

Jonathan Leach, Move Me, acrylic on plexiglass, 2010

The stripes painted on the side facing the viewer, as precise as they are, still show--barely--the hand of the maker. The ones painted on the side facing away have that inhumanly smooth quality. And because the plexi has thickness, the outside layer of paint floats above (and casts a shadow on) the inside layer.

Jonathan Leach, Move Me detail, acrylic on plexiglass, 2010

Jonathan Leach, Move Me detail, acrylic on plexiglass, 2010

Leach also plays with multiple canvases put together, as in

As Predictions Suggest.

Jonathan Leach, As Predictions Suggest, acrylic on canvas, 2010

Jonathan Leach, As Predictions Suggest, acrylic on canvas, 2010

Works like this inevitably remind me of

Peter Halley. Like Halley, Leach is building a composition out of specific formal elements. The work therefore recalls earlier geometric abstractionists and even minimalists. But it also seems to deliberately recall things or signs (literally) that we encounter in the world around us.

As Predictions Suggest has elements of warning signs (the diagonal stripes), maps, and infographics. Even the fluorescent colors are highly suggestive of warning signage. This piece seems to be saying, danger ahead.

I would never have a reaction like that to a piece by

Myke Venable. By using diamond-shaped canvases, he does recall the shape of certain traffic signs, but I don't think this is intentional. I think Venable's intentions are purely formal. At least, that's the reaction I have to his work when I see it.

Myke Venable, Cadmium Red/Violet, water-based enamel and acrylic on canvas, 2009

Myke Venable, Cadmium Red/Violet, water-based enamel and acrylic on canvas, 2009

There are two ways to look at this art. One is to think in metaphysical terms, staring at the colors and thinking about the nature of color and the effect of one color next to another. And perhaps contemplate the cosmos as the same time. In short, view the paintings in a way similar to how

Kazimir Malevich and

Yves Klein. I respect that, but it's not a road I can follow as a viewer. The other way to approach these works is to think of them as a challenge the artist set for himself. Give yourself constraints--extremely limiting constraints--and try within these constraints to create a work that looks beautiful, that looks

right. When I heard

Robert Irwin speak at Rice about his early minimal paintings, this was how he did it. My old teacher,

Stella Sullivan, worked this way on her symmetric geometric abstractions (which can be seen right now at

William Reaves Fine Art).

However Venable creates the work, the result is appealing. (That's why I bought

his piece at the Lawndale retablo show.)

Leach, Guidry, and Venable each work with flat colors, minimizing the visible

hand of the artist. In that regard,

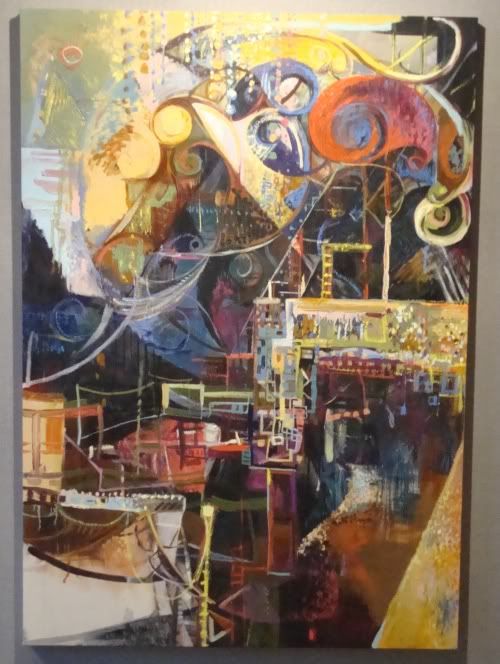

Katherine Veneman is the odd artist out. Her work is gestural and painterly, and mark-making is clearly something important to her. Her work comes more directly out of the American abstract tradition.

Katherine Veneman, Pause, oil and oilstick on canvas, 2007

Katherine Veneman, Pause, oil and oilstick on canvas, 2007

Even her use of an oilstick to draw lines on the canvas recalls pre-drip

Jackson Pollock. But her work otherwise doesn't resemble his at all. The swirling curliques here, the complex overlapping calligraphic arabesques, actually made me think of the work of

Lari Pittman when I first looked at this piece. Veneman's work is far more spontaneous and gestural, but the density and curvilinear marks are similar.

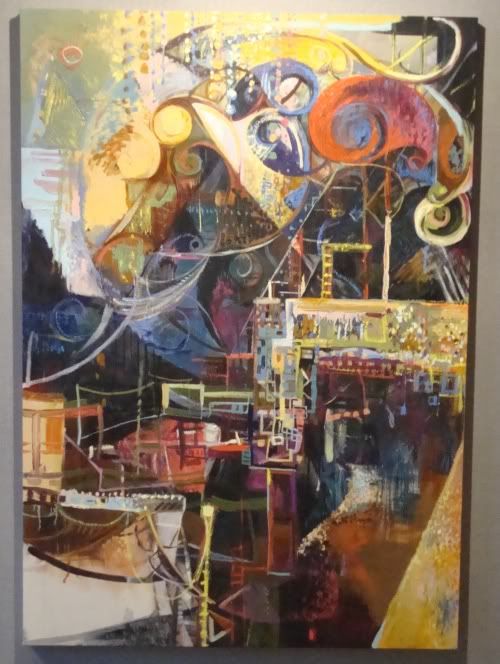

Katherine Veneman, Charting the Territory, oil, oilstick on canvas, 2002

Charting the Territory

Katherine Veneman, Charting the Territory, oil, oilstick on canvas, 2002

Charting the Territory, on the other hand, made me think of

Roberto Matta. And maybe that is the origin of her work--those late abstract surrealist works by people outside the main surrealist circle, people like Matta, Lam, and the American artists who later became abstract expressionists. This is a stream of abstraction that is always in danger of veering into kitsch--but I think Veneman avoids this pitfall with her beautiful canvases.

One final image for you, only tangentially related to this show. Here's Jonathan Leach dressed up as the BP oil spill.