The collector's mania sneaks up on you. I'm in my super-cluttered bedroom looking around, and there are 51 visible artworks (and many more in portfolios on my bookshelves as well as artworks hanging in other rooms). They range from a painted postcard sent to me by Earl Staley and silkscreened limited edition beer-bottles with art by Ron Regé, Jr. and C.F. to paintings by Lane Hagood, Rachel Hecker and and Chris Cascio. I'm not saying this to brag--well, maybe a little--but to point out what all serious collectors come to realize--that they have a lot of stuff and will someday need to dispose of it.

We think of collectors as rich people, but despite the shocking auction prices we read about, the reality is that almost anyone can collect art. Small artwork, prints, art by non-"big name" artists can all be pretty affordable. If you can buy directly from an artist, that usually saves you some money. Sometimes you can trade for art--if you offer a service that artists need. (Hence the art collections of dentists.)

The Vogels are the gods of this approach to collecting. A quick recap of their story: Herbert Vogel was an amateur painter who worked for the post office. His wife Dorothy had a job at a public library. They loved art. They were really into pop art when they got married in 1962, but it was too expensive for them. So they started buying minimal art (not quite yet the new thing when they started). They made a deal with one another--they would live on Dorothy's salary and buy art with Herbert's income. And they did, for decades. In the end, they had a collection of over 4000 pieces of art, which they donated to the National Gallery. In 2008, a really entertaining film , Herb & Dorothy by Megumi Sasaki, was made about the couple. And that seems like it should have been the end of it. The problem is that Herb and Dorothy kept on collecting and kept on donating to the National Gallery, which finally said, enough! As big as the National Gallery is, it just couldn't absorb 5000+ pieces of art.

So they came up with a wonderful solution. They made a gift of art to 50 museums--one in each state--of 50 pieces of art. This is the 50x50 program. Thus 2500 pieces of art were distributed all over the country. And Megumi Sasaki filmed a sequel, Herb & Dorothy: 50x50.

The Blanton Museum at the University of Texas got the 50 pieces of art reserved for Texas. I saw them when the Blanton mounted an exhibit of the work, and one thing I noticed is that not every artist they collected has ended up in the canon. The Vogels had an amazing ability to pick "winners," but no one bats a thousand. (Interestingly, the Blanton also received James Michener's large collection of modernist art after his death. In the book American Art since 1900

That's one thing the new documentary examines--artists who haven't achieved any particular fame whose work was collected by the Vogels.

Charles Clough with the Vogels at the Metropolitan Museum (still from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

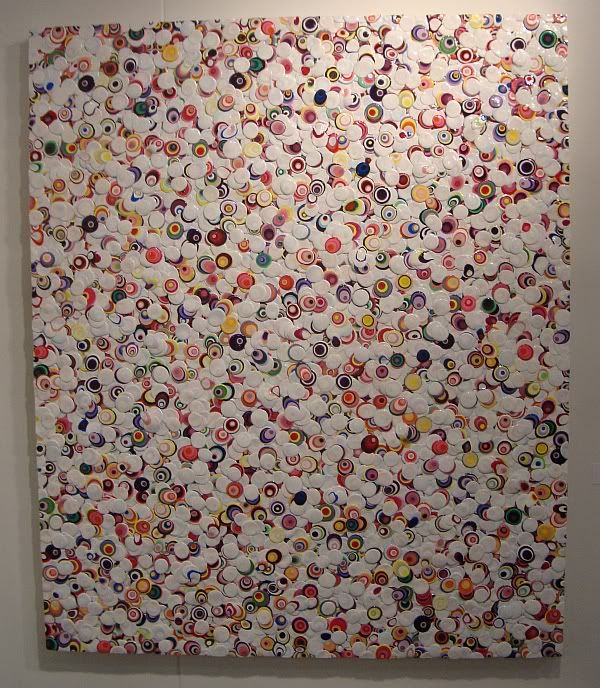

For example, the film looks at Charles Clough. He is an abstract painter who came out of the same Buffalo scene that spawned Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo (Clough was a co-founder of Hallwalls). The Vogels collected a large number of his pieces (127 are part of the 50x50 collection), and he is one of the artists whose work ended up in all 50 museums. But his career as an artist has been rocky. He admits to having hardly sold anything in the previous 10 years. He points to a map of the USA covered with thumbtacks. Each one represents an artwork in a museum. And two-thirds of them are a result of the 50x50 program.

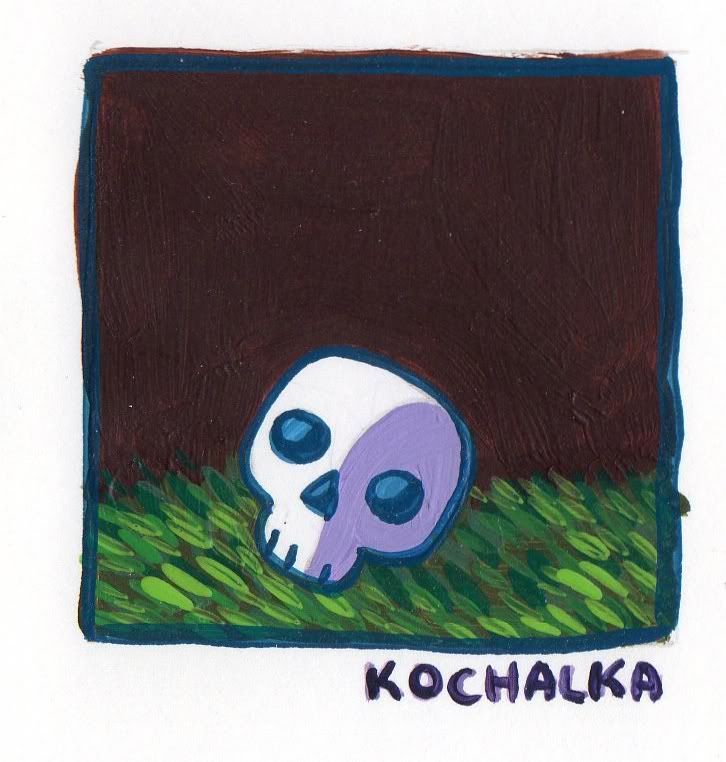

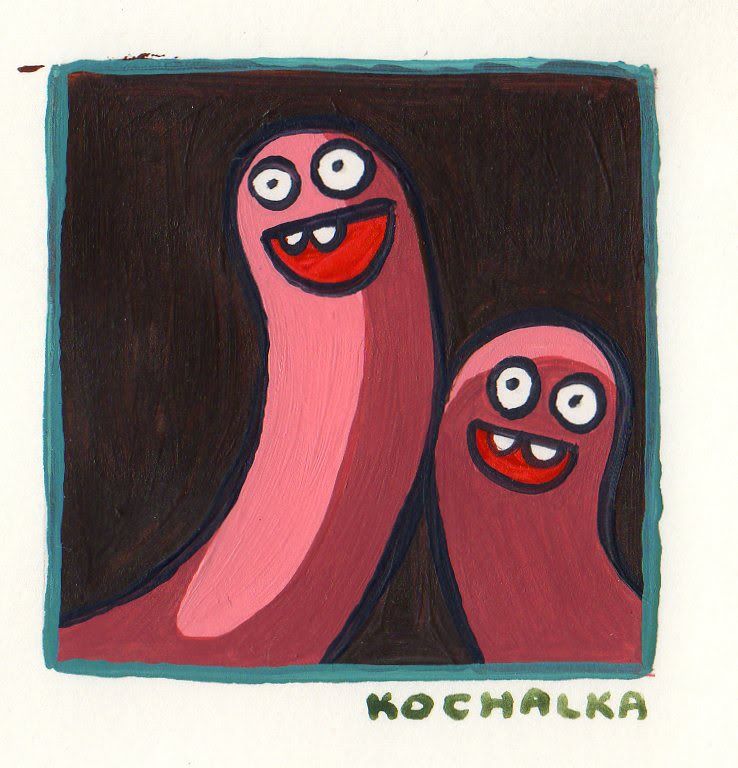

Charles Clough painting (still from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

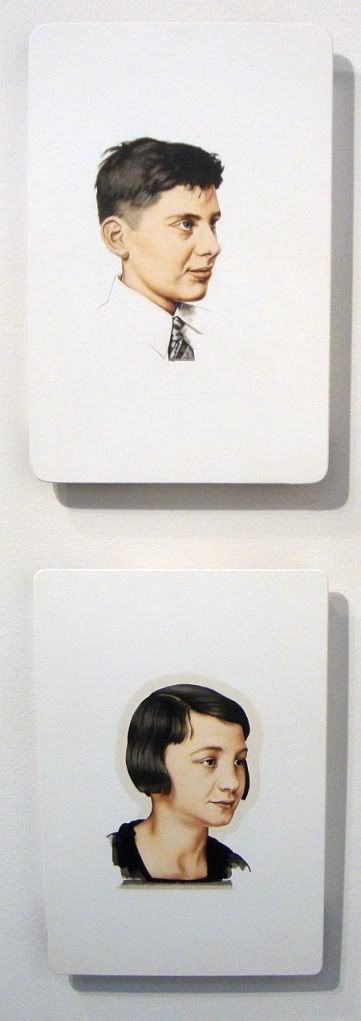

Another artist who never achieved fame was Martin Johnson. Johnson had some success in the late 70s and early 80s, but eventually moved to Richmond Virginia to run the family business, which represented plumbing supplies to buyers.

Martin Johnson and the family business (still from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

As it turned out, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond was one of the recipients of the Vogel collection, and they were amazed to learn that one of the artists whose work they received lived right there in Richmond.

Martin Johnson and his work (still from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

Artists whose moment of success happened decades ago are suddenly finding their work in museums all over America. For artists like Clough, it could mean a second chance at success.

The artist who most exemplifies the Vogel collection is Richard Tuttle. Herbert Vogel was quite close to Tuttle, and Tuttle is represented by 336 pieces in the 50x50 collection--enough for each museum in the program to get at least six Tuttles.

Richard Tuttle with the Vogels (still from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

As it turns out, he's not super happy about the 50x50 program. He would have preferred to see the collection stay in one piece, even if it meant storing most of it. But he's realistic and is shown visiting with curators in Maryland to discuss the best way to display his work from the collection.

Richard Tuttle at the Academy Art Museum in Maryland (still from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

Of course, Tuttle is a pretty difficult artist to love. Most of his work in the collection consists of pieces of lined notebook paper with one or two small watercolor marks on it. This is pretty challenging work, especially in provincial museums in Montana or Alabama. How to show this work in these disparate places is the main subject of the movie. The filmmaker traveled to several of these far-flung museums, including small museums in Honolulu and Fargo, North Dakota. Stephen Jost, the director of the Honolulu Museum of Art, addresses this head on. He knows the work is difficult for many visitors, and the Honolulu Museum has worked very hard to help viewers engage with it. One scene shows children playing a game with the art--they have a guide to all the pieces with little image excerpts, and they are in a race to see who can find them all on the walls first. But Jost acknowledges that there are some viewers who are just plain hard to reach in general and especially with the art from the Vogel collection. These viewers are teenagers and young adults.

Sullen teens at the Honolulu Museum of Art (still from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

What some of the museums have done is make the Vogels the focus of the exhibits--telling their story. The Blanton had the first Vogel documentary running continuously. Some museums actually recreated parts of the Vogel's apartment, down to stuffed cats and turtles (the Vogels never had children--they had pet cats, fish, and turtles).

The Plains Art Museum (still from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

Places like the Plains Art Museum were thrilled to get the gift. Director Colleen Sheehy states her pride in being in the company of LA MOCA and the Albright-Knox Gallery, who also received Vogel gifts. She used the Vogels themselves as the way to interest viewers in the work. She explained it this way: "The work might seem difficult, but they're so accessible." She actually commissioned a local artist, Kaylyn Gerenz, to create a stuffed animal version of one of their cats to be exhibited alongside the work in a small recreated corner of the Vogel's apartment.

One of the museums they donated the work to, the Las Vegas Art Museum, abruptly closed in February 2009, a victim of the recession which hit Las Vegas especially hard. Part of the conditions for accepting the gift were that if you closed, you had to give it to an approved museum in the same state. In this case, the work went to the Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery at UNLV. By focusing so much on several small, regional museums, Herb & Dorothy: 50x50 almost becomes a documentary about provincial museums. It's fascinating to see how they strive to stay relevant and stay afloat.

Herbert Vogel died during the filming of this documentary. The Vogels had already stopped collecting, and their apartment was emptying out.

Before and after (stills from Herb & Dorothy 50x50)

After you've given away your life's work, I guess passing on (at the ripe old age of 90) is not so bad. But I worry about Dorothy (now 78). Will an apartment with no art and no Herb be too lonely for her?

One more interesting thing about Herb & Dorothy: 50x50. It was partly financed by a Kickstarter campaign. They did a typical thing--gifts of a certain size would get you a download of the finished movie, and a little more would get you the DVD. In short, they presold the movie. I was pretty sceptical when I heard about it, mainly because I didn't really believe there was anything else to say after the first movie. But I went ahead and donated enough to get the DVD, and I was very pleasantly surprised. By focusing on artists like Charlie Clough and Martin Johnson and museums like the Plains Museum and the Honolulu Museum, Sasaki created a completely new documentary around the Vogels. It's an informative, moving documentary.