Regina Agu's show Visible Unseen is the sixth exhibition in Fresh Art's 2012 ARC Exhibition series. The show both exemplifies its title and more than holds its own in this impressive series, which showcases emerging Houston artists.

I spoke with Regina Agu at the opening. She is lithe, graceful, unassuming, and very approachable. She casually and confidently interacted with the audience, patiently and repeatedly providing context about the pieces and answering audience member's questions. Often, I heard her repeat herself because her work invites inquiry. We the viewers, however, frequently had the same thoughts but didn't have enough foresight to approach her en masse and let her answer our inquiries just once.

Despite having talked with her at length about "...biological, historical and scientific references coupled with current event commentary (through a) present day lens" (to quote a post by Nathaniel Donnett on the events FB page), I wouldn't have known she was a graduate of Cornell with a Bachelor of Science in Policy Analysis and Management or a world traveler. Nevertheless, I should have. Not because she's wearing a Cornell cap or beginning every other sentence with "when I was studying Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell..." or "...the last time I flew into Lagos..", but because a definite mental acuity and worldliness permeated her conversation. In other words, it's all there, visible but unseen.

Her art work in this exhibition is the same. The works are about disparity of medical ethics employed by physicians on various ethnic groups, the ownership and origination of knowledge, and the cultural and personal vs. the stereotypical. However, when you first approach them, that's not necessarily your first impression. The works are also meticulously crafted and beautiful and reticent to reveal their themes. But if you spend some time with the art and the artist, if you dig, they open up and reveal themselves.

I dug--with a lot of help from Agu--and here's what I discovered.

The series began with the work "Night Doctors", which was originally created for the show entitled "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks: A Response by African-American Artists" at Mountain View College in Dallas, TX. The show was in response to and in support of the publication of the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot. In this book, Skloot reveals how after Lacks' death from cervical cancer, doctors took tissue samples without her or her family's knowledge or permission. The medical community then developed those cells into the HeLa Immortal Cell Line, which has been used to develop cures and make advances in cancer, AIDS, and other research.

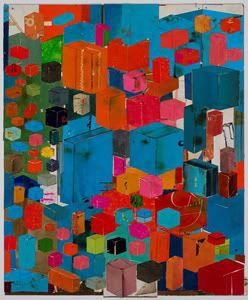

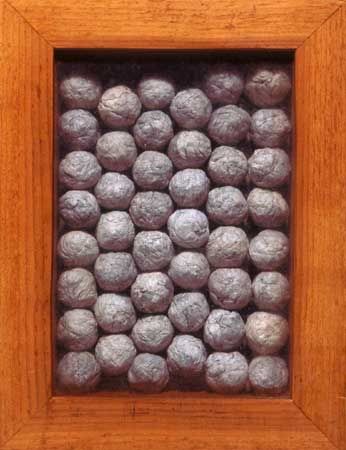

Regina Agu, Night Doctors No. 1

Another chapter in the book, "Night Doctors," from which the seminal work in this series derives its name, details how fear tactics were used on slaves to perform experimental procedures and reveals the trafficking from the South to the North of slave corpses for medical resources. (Agu summarizes it much better than I on her blog.)

Informed by these facts, I realized that in a number of pieces in which she uses bibliography pages from medical text, what I was witnessing is an aesthetic act of reclamation.

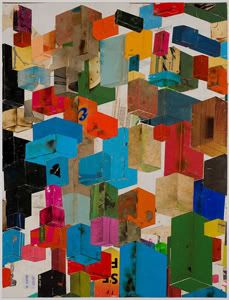

Regina Agu, The People Could Fly

The People Could Fly is a perfect example of employing formalist elements and collage to "explore hidden and forgotten histories". She imposes a metaphorical figure composed of repurposed images on to the bibliography of a medical text. Gold paint blocks out all the names, dates and studies from which this knowledge originates. By systematically eliding all the knowledge attribution from these medical documents, Agu imbues the work with a gilded formalism. Her aesthetic choices are more than merely formalist decisions about how to balance the composition. These marks challenge the fallacy that knowledge originates from the work or insight of a single individual (a theme that John Lienhard often ridicules in his series the Engines of our Ingenuity). They also attempt to restore credit to the patients and participants of these medical experiments by denying the medical myths perpetrated by these attributions. Symbolically, she eliminates from the history books those credited with the medical discoveries in the same way many of them discounted or explicitly eliminated the contribution of their marginalized patients.

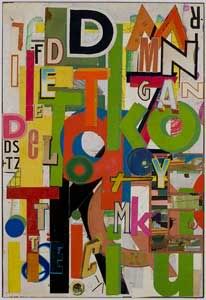

Regina Agu, Introduction to ...

In Introduction to... Agu "doctors" the stately portrait photos of many of the doctors who engaged in this socially accepted but exploitative practice. The aesthetic choices made in Dental Records (Heirlooms) exemplify the power of Agu's techniques. I love the way in which the light blue, alphabetic separator for Js underlines the gilded teeth and anchors the piece.

Regina Agu, Dental Records (Heirlooms)

Oracle is superficially beautiful, but ultimately unnervingly eerie. At first glance, the female figure is mesmerizing. However, upon closer inspection, the cutting up and segmenting of the body in the image invokes the memories of all the bodies parts that were experimented upon. Agu's Oracle predicts a cure, but it also illustrates the cost to those involved in developing that cure. It alludes to the fact that at one level the medical community treated the bodies of African-Americans and other ethnic groups as bodies of parts that were merely parts of experiments.

Regina Agu, Oracle

Another group of Agu's works uses similar techniques to address an alternative theme, that of the stereotypical vs. the personal. In this series of collages, I see Agu "excavate ideas and rituals that [she] inherit from family, from our backgrounds, and from our most basic instincts" as she declares in her artist statement. In works such as A Rare Specimen - Mami Wata Suite No. 3, Agu uses collage to combine the contemporary with the traditional, personalizing her rendition of Mami Wata, a spiritual-mythical figure that embodies African beauty.

Regina Agu, A Rare Specimen - Mami Wata Suite No. 3

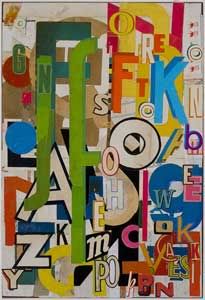

Guaranteed Wax Block Prints plays off a claim that all fabric makers in Nigeria make because of the prevalence of cheap knock offs.

Regina Agu, Guaranteed Wax Block Prints

Regina Agu, installation at Fresh Arts

Her one installation continues the theme of discovering through uncovering. In it she has covered one wall of the gallery with personal pictures from her childhood and her travels. Over the course of the exhibition, she will cut-tear-rip a familiar textile pattern from her childhood in Nigeria into the pictures. This act personalizes and reclaims the fabric pattern for herself as she not only re-creates it with her hands, but creates it out of her own images and memories.

I certainly plan to return before the show ends on October 26, 2012 and see what emerges. I recommend attending her Artist Talk at the Artist SPEAKeasy: Wednesday, October 17, 6:30 - 8:30 p.m.

(Thanks to Jenni Rebecca Stephenson from Fresh Arts for coordinating and Regina Agu for providing all the photos except the last one.)